DM: What is your own history with art?

RM: My art was largely rejected by the university, and so I left, and I’m basically self-taught. [Melgar had studied at the University of El Salvador.] Contact with other artists diversified my work, and it has transformed a lot over time — until now, when pieces generally come out something similar to what I have rolling around in my head.

DM: Can you tell us a bit about your slogan, “Any wall is good enough to hang my art upon?”

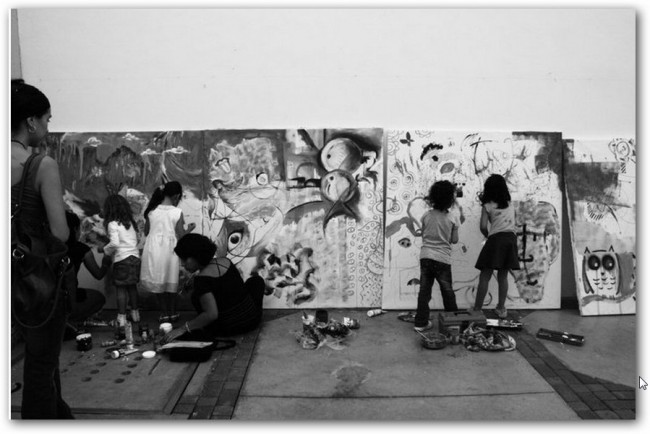

RM: “Cualquier pared es buena para colgar mi arte.” [My slogan] is my philosophy; if I write a manifesto someday, that will be the first of all chapters. Modern artists place value on art if it’s in a prestigious gallery or a museum, but that is funny to me. I think that what gives value to a work is the personal process it is required to make. I’m talking about a cathartic process where three things are involved that can’t be left out: technique, creativity-imagination, and spontaneity. I like to feel that the piece changes even as I’m producing it. Really, it’s all a long process of communication with the piece. And sometimes during creation, I put the piece in front of me and just look at it, contemplate it, and after that I can understand a bit more of how the world might see it. Any space is good enough to share your piece; think of it as your child. The piece is your child and you don’t need to show him off in a castle so that the world will see how beautiful and restless he is.

The real strength of my pieces are that they represent how I live my life — so much so that I don’t like to say much about them. They have enough force on their own. Any wall is good enough to hang my art upon, even if I’m doing an exhibit on the street. Both the street and the museum have their own richness.

DM: Can you tell us about a moment that has influenced you as an artist?

RM: Cancer. [Melgar had a cancerous tumor in the nasopharynx.] I think that in my work there are two phases: before cancer and after cancer. When I was in the ward, I thought about all of the things I hadn’t yet done, leaving them for another day. I thought of myself as a good artist but I didn’t share anything that I did, so as soon as I got out of there my work took a very different path. With the collective, for instance, we didn’t just decide to be a collective. The way we shared made us a collective — eating together, traveling with our works together. Once when we took a 60-piece show to Guatemala we had to sleep in the street. I think that sometimes people don’t understand that having a collective that does things well implies a lot of sacrifice: time, money, ideas, even sometimes romantic partners. (Melgar chuckles.) What happens is that it’s really easy to make a collective; the tough part is doing something different … continuing to propose new things and never stopping.

DM: What do you think of Salvadoran Art?

RM: Salvadoran art is, on one hand, a very academic and almost snobbish affair sometimes. But it’s also quite complex and has a lot of rich variants. Every stage of Salvadoran art has been unique, and we have truly great figures in our country, but, as in all of Latin America, processes happen too slowly and the fact that we don’t share our knowledge with one another gives us complexes. The worst complex that some have is that we’re a small country where no art happens. That’s a big misnomer.

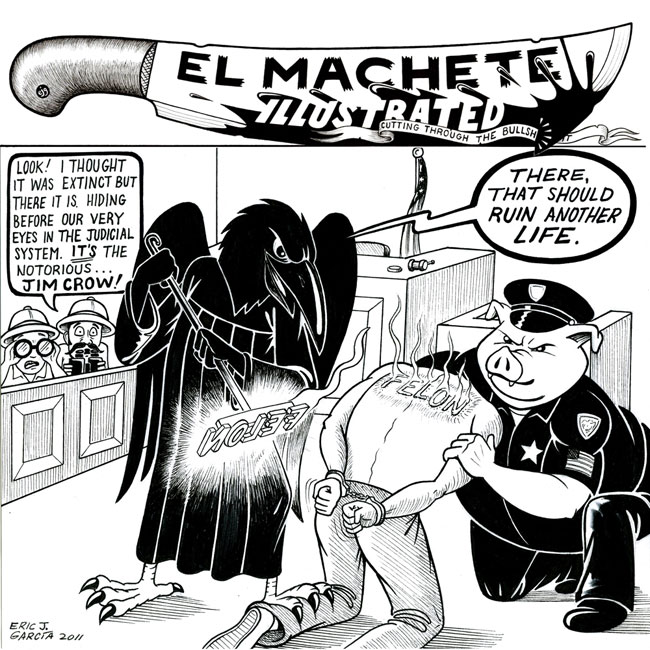

I also see Salvadoran art as a closed space that’s full of fears, because something has made us believe that people can steal your ideas, or that we’re in a constant competition to demonstrate who is the best artist. I think this is partly a result of the daily reality that we live as Salvadoran citizens, and supposedly the art world is full of sensitive people so that’s magnified here. But we won’t have truly bad-ass art until we don’t stop trying to be: trying to be of a certain class, trying to be an “artist,” trying to paint like Europe, trying to be accepted by the critics. We can’t do something that’s not based on our own reality, on our own context. Great artists do nothing more than reflect their own historical time, and the artists in this country suffer from an amnesia that I sometimes think must be self-provoked. As with your average Salvadoran, historical memory doesn’t interest some artists, and that bothers me. We’re constantly living naively in the convulsive day-to-day that we forget to look back and converse with older artists. We urgently need a generational bridge, a space that allows youth and older folks to talk, or we’ll continue committing the same fuck-ups and we’ll never construct anything; we’ll continue merely replicating what we see in other places.

DM: What do you think of Latin American art?

RM: Latin America is interesting. I don’t understand how in a region with so many different realities, the problems facing those who create are always the same. [We lament] the lack of spaces, lack of support, lack of cash — and this has gotta stop. The Jesus Christ Art Savior will never appear, and if we would just give more effort toward producing we’d be dancing to the beat of a different drum. Art collectives from Mexico, Argentina, Columbia and Peru have all proved this. They’ve realized that we’re creators of a Latino aesthetic that goes farther than the typical responses of pseudo-guerrillas or pseudo-intellectuals. When we stop looking at Europe as the vanguard, we realize that we have plenty to work with here.

DM: Who are some of your favorite artists?

RM: I’d say, off the top of my head, Os Gemeos from Brazil, Arnoldo Ramirez Amaya from Guatemala. But if we’re talking about specifically the Salvadoran big guns, I’d tell you: Benjamin Canas, Cesar Menendez, Antonio Bonilla, Yanira Elias and Mayra Barraza … among others.

DM: What else influences your art?

RM: What interests me more than anything is whatever has to do with the modern human being: the implanted necessities of consumerism, modern implanted diseases like stress or anorexia and bulemia, noise, gangs, the economy. I concentrate on the best and the worst parts of being a modern human being, from our daily battles, to sexuality and gender — all of this is part of who we are. I also try to leave a big space in my work to tackle memory. I like how the brain stores memories and how it constructs histories, collective as well as individual. It worries me that our (national) history is made invisible by the international context we live in, so I look for alternative ways to fusion our present context with our roots to build a bit of historical memory. That which we allow ourselves to forget worries me.

Check out some other artists who have been involved with Colectivo Urbano!

Oscar Lopez, Evan Lopez, Miguel Servellon, Sara Boulogne, Rhency Geovani Calo.

– All photos courtesy of Renacho Melgar and Urbano Colectivo.

Renacho Melgar gets money from foreign people and won’t send the paid art. I think this is not a good cultural way, to spread art. The word spread under european artist, that he is a crook and trickster. Sorry for this, but don’t present such people who wants to be artists. Maybe for San Salvador it’s ok. Get more serious! Viva la Art!