Failure and Bravo’s reality show “Work of Art: The Next Great Artist”

By Beth Capper

“Eddie’s composition has simplicity, but did he run out of time on the details? Barbara’s sunny painting has a warm atmosphere, but did courage fail her on the buildings? And Michael has observed the scene well, but has he overemphasized the verticals?” Such questions summarize three watercolors painted by contestants on the U.K. television show “Watercolor Challenge.” The show, which aired between 1998-2001, pitted watercolor hobbyists against one another to depict a tranquil scene each episode — their efforts judged by a group of professional painters.

Competitions of this kind have existed for decades, on and off television, but the U.S. television station Bravo is the first to apply the amateur competition formula to contemporary art, with its reality show “Work of Art: The Next Great Artist” (which aired between June-August 2010). Co-hosted by art collector China Chow and cartoonish French art dealer Simon de Pury, Work of Art brought together fourteen would-be artists vying for a solo show at “the world famous Brooklyn Museum” and ten thousand dollars in cash. The challenge: Make a piece of art every week, related to a loose prompt, some of which — like “make a work of art based on hanging out in an Audi showroom”—were very loose. Contestants were eliminated each episode by a panel of three arts administrators and Pulitzer Prize- winning journalist and SAIC professor, Jerry Saltz.

While the show has similarities to programs like “Watercolor Challenge,” “Work of Art” is more of a reality show than a competition show; the difference is that one focuses squarely on the competition at hand, while the other is more concerned with the interpersonal dynamics of the participants. As reality television goes, it’s routine fare, not entirely different from “American Idol” or “Project Runway.” Unlike these shows, though, the subject matter of “Work of Art” sits a little less comfortably within reality television’s formula. Perhaps because while fashion and pop music are unabashedly market-oriented, art and artists aren’t really meant to be. Indeed, market-oriented art is often thought of as akin to selling out.

“Work of Art” is also different in two other fundamental ways. First, there is little-to-no emphasis on technical skill. Technique is valued by the show’s judges, but only when it enables the transcendent experience to which only art supposedly has unique access. Secondly, and most centrally, “Work of Art” is about sorting amateurs from professionals, as opposed to being a competition between self-proclaimed amateurs. Indeed, any mention of the term “amateur” is only intended as a put-down; bad work is “amateurish,” and to be deemed an amateur is to have failed.

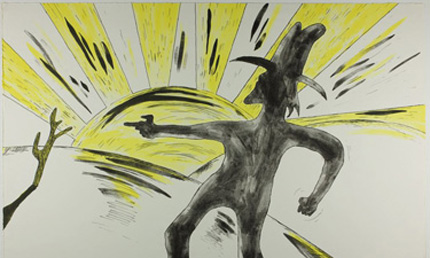

One could say that the appeal of reality television is the catharsis derived from watching others fail. However, “Work of Art” is more interesting than simply watching a slowly unfolding car crash. Part of the fun of watching the show comes from never knowing what the artists will do next, and the most enjoyable contestants to watch are those with less knowledge of what the art world expects from them. Their failure is intrinsic to our enjoyment, just as failure is in many ways intrinsic to the figure of the amateur. Ralph Rogoff describes this in his essay “Other Experts,” arguing that the ways in which amateurs fail to perfectly conform to the artistic conventions we hold as natural draws “attention to the arbitrary and artificial character of cultural codes that structure the production, and reception, of aesthetic products.” Perhaps the most successful thing the contestants on “Work of Art” could have done would have been to fail, and through their failure expose the mendacity of the art world.

What is most depressing about “Work of Art” is that the contestants were unable to carve out their own parameters for success. Indeed the show demonstrates that for many people, the mainstream art world still exerts a strong gravitational pull. Someone should have told these contestants that there is no “get rich quick” scheme for being an artist, and there is more to the life of an artist than blockbuster shows and a review in the New York Times. As artist and critic Mira Schor writes in her essay “On Failure and Anonymity,” “Follow fashion and be fifteen minutes late. Trends are fleeting. A lifetime of art cannot be built on a weather vane.”

Moreover, “Work of Art’s” contestants are the tip of the iceberg. They’re a microcosm for the desires of art students everywhere. Market success and a big gallery show, or the equivalent for moving-image makers, is seemingly what drives a majority of MFA and BFA graduates, whether they admit it or not. The notion of the professional artist has shifted over the last sixty years or so. Time was such that institutions such as SAIC were places where artists learned technique in much the same way as a blacksmith or woodworker learns a trade. Today, technique has been sidelined for concept, and what makes an artist professional has more to do with being recognized as such by the contemporary art world, and, yes, the market. In both cases, the emphasis on professionalism as the degree zero for an artist’s aspirations promoted work conceived within limited parameters.

Schor offers a familiar complaint: “A CalArts graduate presented a paper at a College Arts Association conference some years ago in which she blamed the school for not having prepared her for the realities of the art market … But the logical outcome of this emphasis on networking and salesmanship is hucksterism, self-commodification, packaging at the expense of content. The art precipitated by this imperative to “make it” tends to be fast work that can be sold easily and quickly. Even ‘angst’ must be ‘lite.’”

Just like the job prospects this CalArts graduate had expected her overpriced degree would yield, “Work of Art” can never deliver what it promises. The show’s winner, Abdi, will become famous, but he’ll be famous as a reality TV star, not as an artist. Will money and a show at the much-maligned Brooklyn Museum of Art yield the respect of the art world? Unlikely. Its pathos lies in the fact that its contestants are a hyperbolic version of everyone else who “wants in” to the art world.

What should be taken away from the show is the limited taxonomy of art and artists that it propagates. And only if we stop bolstering the decree of institutions whose aesthetic judgments are at best random, and at worst, completely arbitrary, can we level the playing field.

There’s evidence all around us that amateurism is gaining traction, most notably in experimental film circles. Since film has always been shunned by the art world, it seems filmmakers and historians have less to lose from rethinking whose expressions of creativity are valuable. Individuals and institutions like Skip Elsheimer (A.V. Geeks) and Orphan films have demonstrated that there’s beauty in work left to the trash. Writers like Roggoff and Patricia Zimmerman have written eloquently on the aesthetic importance of amateur art and artists.

There is more to amateurism than the sunday painter or hobbyist. As Roggoff points out, amateurism has been integral to art movements throughout the 19th and 20th century, where “an ethos of amateur production was embraced as both a democratic signifier and an alternative to the increasing professionalization of creativity in a market-driven culture.” Throughout history, artists have created, distributed and exhibited the art and art criticism they want to see, when they want to see it. And what’s more, they’ve been content with amateurism, even embraced it.

To reach a true valuation of the work of amateurs, it’s important to do everything to resist the professionalization of their work. The only way to create a new taxonomy of art and artists is to push for a horizontal economy, rather than a vertical one, an economy in which everything is valued according to infinitely relative parameters of success and failure.

Amateurism keeps art and culture moving, or as Andy Warhol, who loved amateurs, said, “Every professional performer always does exactly the same thing at exactly the same moment in every show they do. That’s why I like amateurs. You can never tell what they’ll do next.”