Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe at the Museum of Contemporary Art

On the top floor of the MCA, the world of Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983) has come to life. Plans, models, pictures, letters, diagrams, videos and sculptures populate the space, giving form to the brilliant inventions and heartwarming character of this seeming enigma of a man. Perhaps the most fun thing about this exhibition is that it exposes and explodes the myth that has for so long separated the artist dreamer from the engineer realist in our lexicon. Fuller’s work shows where life and art intertwine, and that the visionary comes in all sorts of guises—some of them actually practical.

The exhibition takes us through a relatively chronological tour of Fuller’s development, demystifying and decoding much of his abstract language and unfamiliar forms, beginning with a video called Buckminster Fuller Meets the Hippies in Golden Gate Park. While not as stoned as his crowd, “Bucky” seems to fit right in, with his existential language and his hyper-active demeanor. It is really quite simple, he tells us: we are not using the world’s resources correctly. Renewable energy, recycling, sustainable living. All the buzz words of today, only the film is from 1967.

The Diligent Documenter

In the first room of the exhibition, we learn that after losing everything, including his first child, the young Fuller almost took his life by plunging into Lake Michigan at the age of 32, but instead decided to change the world. Possibly apocryphal or, more probably, just a dramatic autobiographical device, Fuller claimed that this moment was when he decided to become “Guinea Pig B”—his own life-long science experiment: “an experiment to find what a single individual can contribute to changing the world and benefitting all humanity.” Either way, this moment or period of despair was followed by a lifetime of great ingenuity and productivity; a life from which almost every scrap of paper and residue has been conserved.

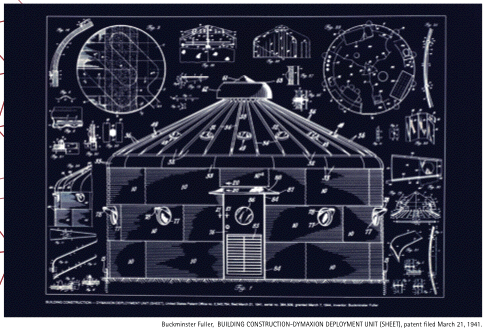

Throughout “Starting With the Universe” are displayed parts of Fuller’s Chronophile, a journal composed of letters and notes, that grew to be thousands of pages long, along with many drawings and plans of his inventions and forms. Included are some of his earliest drawings (c. 1927): images of towers radiating off the earth’s surface and into the atmosphere, and skyscraper-like buildings depicted as weighing less than a standard home measured upon the scales of justice.

Not to be missed among the many papers and memorabilia is the small telegram that hangs next to Noguchi’s chrome-plated bronze Portrait of R. Buckminster Fuller (1929), explaining Einstein’s theory of relativity (in the requisite 50 words or less), which Fuller sent at Noguchi’s request.

The Stable Triangle

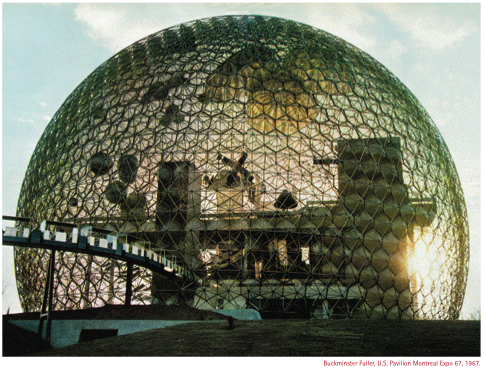

Distributed throughout the galleries are videos of Fuller, either explaining his inventions and ideas or interacting with people in his work and life. These films are instrumental to understanding some of the underlying notions behind his radical forms of architecture—including his investment in the triangle and the geodesic dome as the fundamental forms for building.

The videos also give a great deal of insight into the kind of man Fuller was, portraying his quirky social awkwardness along with his endearingly charismatic appeal. For instance, off in a side gallery is displayed a video of the young Fuller, dressed in a three-piece suit and spectacles, uncomfortably (but energetically) showing off the skeleton of his model for the Dymaxion House. He explains its structure and its basic form: how we use the cube as our basic structure, even though the sphere is the fundamental building block of the universe.

In a later video a couple of galleries over, using connective rods (used like flexible Erector Set components) he demonstrates how the triangle is the most stable geometric form by almost clownishly draping himself with the bending and unwieldy polygons, as he slowly breaks them down into a basic equilateral triangle.

The Charismatic Builder

The most interesting pieces in the exhibition are, however, the models of buildings, geometric forms, prototypes and more that take up most of the floor space of the exhibition. While these bizarre structures are brought to life by the ephemera (photographs, documentation, illustrations, etc.) and stories that surround them, they help the visitor understand just how “out there” Fuller must have seemed during his time.

The second room of the exhibition is devoted to Fuller’s 1929 show at Marshall Fields. It explains his switch (at the urging of the store’s marketing executives) from the term “4D” to “dymaxion”: a conglomeration of his most repeated terminology—dynamic, maximum and ion. And so, the Dymaxion House, and all of its dymaxion offspring, were ushered into the world. An aluminum model of the house takes center stage in this room, while the small third gallery is devoted to the dymaxion car: a teardrop shaped, three-wheeled mini-van, that was the futuristic hit of the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago. Included is a cast of Noguchi’s model rendering of the car.

The next gallery displays his futuristic Wichita House (an alternative to the dymaxion model of easily built and transportable housing), while the last gallery has two prototypes of his rowing needles and the model for his U.S. Pavilion for the 1967 Montreal Expo.

The All-Inclusive Sphere

In 1940s, Fuller began working on his Dymaxion Air-Ocean World Map project: an undistorted map of the earth’s surface, used to depict the land and water masses in order to accurately assess the Earth’s resources (and pollution). The map breaks the world up into numerous triangular sections that fold together to form an icosahedron (a 20-sided form). Along with his World Game (a play on the popular term: “war games”), the map offered up an interactive way to explore the then newly burgeoning global economy. However, before modern computing and internet databases, his World Game was unrealizable, and many of his projects, such as the Wichita House, were deemed failures, because the global, sustainable and environmental consciousness behind them were beyond the horizons of his contemporary consumers’ desires.

It is at this point in the exhibition that you realize that you have reached the mid-point of the show having seen models for houses, cars, utilities and maps that display thinking so far ahead of their time that they exceed the scope of the technology that was available to Fuller. This realization is brought home by the array of models and forms that you encounter here, which play with the geometry of the sphere and atomic compositions. Although it was unknown during Fuller’s time, many of these forms turned out to be the microscopic building components of all natural life. In 1985 (two years after his death) the family of carbon molecules C60 was discovered with the same structure as his geodesic domes. It was fittingly named Fullerene, and its forms are now affectionately referred to as “buckyballs” and “buckytubes.”

The Energetic Teacher

Documentation from Fuller’s time at Black Mountain College, Institute of Design in Chicago and Southern Illinois University compose the anchor points to the exhibition. They show him working with students and artists to develop incredibly strong and self-sustaining geodesic structures as building components. These examples include a hilarious wall-sized image of his students and himself hanging off one of these dome-like forms. According to Fuller’s daughter, Allegra Fuller Snyder, his work really changed when he started teaching and working with students. She said that he always believed

that the young mind was the way the brain was actually supposed to be.

His grandson, Jamie Snyder, said that Fuller would talk about a “design revolution” based around the tetrahedron as the simplest stable structure (as was demonstrated in the videos). He thought that the mostly two dimensional and limited three dimensional geometry being taught at schools was out of date, and so he immediately inducted his architecture and engineering students into a world that went beyond the xyz axes they had been instructed in.

The Legacy

The curators of “Starting with the Universe,” both at the Whitney Museum of American Art and at the MCA, repeatedly assert that the moment is “ripe” for a reassessment of Fuller’s work. In an age where sustainable living and ecological crisis are our realities (no matter what the radical conservatives claim), we can no longer look at his inventions like they are built for another planet. We now read about his ideas and the opportunities that they offered over 40 years ago, which we were not globally and environmentally conscious enough to pick up on then, and realize that these houses and cars could have changed or prevented the situation we now face. In my case, I was left asking the wishful question: would the Dodgers still be in Brooklyn if Buckminster Fuller’s domed stadium had been built in the ‘50s? Of course, this is a somewhat silly personal-desire-related question, but considering that both baseball stadiums in New York City were rebuilt/replaced this year, perhaps it is not all that off point.

This was the first show that I have ever seen at the MCA that left me not only exhilarated, but planning multiple return visits. And, after my second trip, I still have not had the chance to spend quality time in the “Dymaxion Study Room:” the last room of the exhibition. So, maybe when you go, you will find me there reading about spheres and what else could have been!

On view through June 21 at the MCA, 220 E. Chicago Ave., 312-280-2660. Hours: Tues. 10am–8pm, Wed–Sun 10am–5pm. Admission free on Tuesdays and for SAIC students.

Hi Emily,

Can’t believe that nobody has at least said ‘nice job.’ Thanks for spotlighting one of my, all time hero’s. Certainly a visionary and a man born a bit ahead of his time, much of what I’ve discovered in life has been the result of following some of the trails that Bucky so brilliantly blazed.

Nice Job,

James Maas

7Bends.com