The American Folk Art Museum’s argument for “Dargerism”

Coupling Henry Darger’s drawings with a mix of works by eleven contemporary art up-and-comers, the American Folk Art Museum in New York presents a fascinating exhibition about mythmaking, war and the presumptive innocence of childhood. Inhabited by hybrid creatures garnered from influences ranging across our visual culture and into the depths of our imaginations, “Dargerism: Contemporary Artists and Henry Darger” tackles the tropes of storybook innocence – bikes, bows, pigtails and all – and their crossover into a darker side of double entendre, danger and evil.

The show highlights the distinctive qualities of Darger’s world of fantasy, encapsulating the troubling or sinister character of his narrative about hermaphroditic Girl Scouts escaping nuclear fallout in their Smurf-like landscapes of overgrown flowers, their Dick and Jane suburban scenes set afire, and their Gettysburgian battlefields.

The show argues that he had an indispensable and irrefutable influence on a younger generation of artists. From Robin O’Neil’s epic drawings of stark vistas that are sparsely inhabited by their adventuresome and suicidal travelers, to the bustling, highly orchestrated, yet chaotic scenarios concocted by Anthony Goicolea, the quality of both persona and landscape that Darger creates are retained and expanded upon: one of quirks, uncertainties, and a pervasive discomfort couched in the comforting aesthetics of the recognizable and childlike. The myths, imagery and incongruities that characterize his narrative are transformed into new metaphors and scenarios (some more successfully than others) for a society that seems intimately known, yet beyond comprehension. Like Darger’s Coppertone girl warriors, these younger artists depict heroes that retain their innocence despite their disconcerting characteristics. No matter the ambiguity or depravity of their circumstances, these children seem to be the victims of them, thrust or born into their strange situations.

THANK HEAVEN FOR LITTLE GIRLS by Justin Lieberman

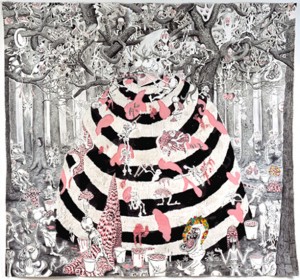

While the contemporary artists are not self-taught, as Darger was, many of them claim that it was his influence within their education that allowed them the freedom and encouragement to indulge in their own fantasylands and to take on the roles of mythmakers. Trenton Doyle Hancock even incorporated Darger’s myths into his own great narrative, connecting Darger’s creatures to the mythic “mound” from which his tale emanates. Meanwhile, Amy Cutler and Justine Kurland make Darger’s presumptive girl warrior, who is subject to both her own self-torture and to the horrors of the outside world, into their protagonists. Cutler’s Rapunzel-pigtailed girls pull houses with their heads and become entangled with each other and with monkey bars. Within a dollhouse they save horses, slaughter pigs and commune with the ghostly apparition of a bull.

While Jefferson Friedman, Yun-Fei Ji, Michael St. John, and Grayson Perry play relatively minor roles in the show, it successfully acquaints viewers with the works of Cutler, Hancock, Kurland and O’Neil. Justin Leiberman makes a short but powerful appearance with a couple of his MFA thesis collages of PhotoShopped Darger landscapes inhabited by bodies from Jock Sturges’s images of men with their genitals tucked under, attached to the heads of pre-teen beauty-pageant girls. Paula Rego’s large and enigmatic paintings from her series depicting Darger’s “Vivian Girls,” make three staggered but strong impressions as well. However, it is Goicolea (rather than Darger) who seems to dominate the show.

With paintings, photographs and videos, Goicolea’s diverse use of media piece together a complex narrative that reminds us why the boys of Lord of the Flies disturb us and touch us so greatly. Goicolea’s boys are both kidnapped and kidnappers. Their hooded sweatshirts or shiny yellow raincoats act as both disguises that hide their identities like thieves and costumes that betray their innocence and boyhood. His narrative, explained in his 15-minute video Kidnap (2004), circles around his own obsession with a story of a boy kidnapped from his room in the night and never found. The storyteller talks of his attempts to fake his own kidnapping in order to fool his would-be assailants. The obsessive reenactment of the preemptive kidnapping – including the donning of its created uniform – becomes indistinguishable from reality to the boy due to its constant repetition, until one day he finds that he actually has been kidnapped.

Image: AND THE BRANCHES BECAME STORM CLOUDS by Trenton Doyle Hancock

While presuming that “Dargerism” may be as influential as, say, Minimalism on the current generation of artists may be ludicrous, Brooke Davis Anderson certainly makes enough of an argument with this exhibition to link the current trend of epic mythmaking, narrative and fixation on childhood imagery back to Darger as a prominent inspiration. The absence of Lee Baxter Davis, in the presence of so many of his students, for instance, points to some of the holes in the claim, but in no way discounts the legitimacy of Darger’s influence. And whether you agree, disagree or could care less about the nature or extent of his affect, the show offers an interesting array of artists, whose various interpretations of our current political and cultural condition tackle the issues in a disturbing, yet exhilarating visual and conceptual manner.