by Dimitry Tetin

SAIC stays ahead of the curve with a program that tries to keep up with the changing art-making practices.

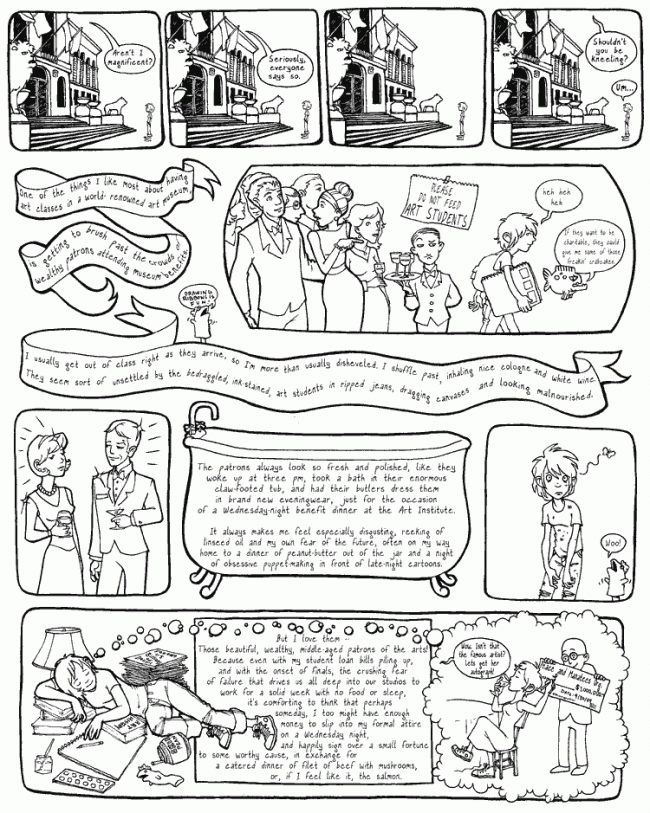

There is a certain amount of privilege that is associated with attending art school. Entering the rotating doors of the Michigan building for the first time to attend orientation, a week before the start of classes in the First Year Program, the student is swept up into the penthouse of the ivory tower. Public intellectuals, regularly quoted in the leading publications, recluses who just received rave reviews in the European press for their piece in the latest Biennale, committed craftsmen who couldn’t care less about the latest neo- or meta- theory and many more “types” are housed under the three roofs of the SAIC. But as orientation goes on, the student becomes hungry and sleepy, the speeches blur into one, and one fact becomes clear: these people work for a living. The realization might not strike you at that particular moment, it might have come years before or will come years later.

The mission of the school is to train artists. The school is an educational institution that allocates funds and physical and human resources to fulfill that mission. Jobs are cut or created, inventory purchased or sent to salvage in order to maximize production. It is not Adam Smith’s pins that the Art Institute churns out. The institute is in the business of exhibitions, publications, performances, the creation of cultural assets. The success of each student, alum, staff or faculty member increases the reputation of the school. Exhibitions and events like the Fashion Show and the Art Sale are open to the public and serve an important purpose in exposing the school to the community as well as to the professionals in the field. Curators and collectors check out the BFA and the MFA shows looking for fresh talent. The shows’ primary goal ought to be to showcase the work to one’s peers, but students still believe that at these events, “My art career can start tonight.” The ArtBash, an exhibition of work from First Year Program (FYP) students, on the first floor of Gallery 2 at 847 W. Jackson, is hosted in conjunction with the MFA show which is relegated the second and third floors. “This is where it all begins and this is where it will all end!” the shows proclaim to prospective students and parents. The FYP students and MFA graduates are peers. Both groups attend the same institution under the umbrella of the same interdisciplinary conceptual educational philosophy that is intended to pervade all of the school’s curricula.

The Rhode Island School of Design, tied with SAIC in rankings, requires its incoming freshmen to take separate classes in drawing, 2-D design and 3-D design, as well as art history and liberal arts classes. SAIC’s neighbors, Columbia and UIC, require incoming art students to take classes with titles like Beginning Drawing, Fundamentals of 2-D Design, Foundations of Photography I, Sculpture I and Introduction to Time-Based Visual Arts. At SAIC, the studio requirement for the first-semester first-years consists of 6 credits of Core Studio and 3 credits of Research Studio. The Core Studio, co-taught by four faculty members from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. on two consecutive days of the week, is intended to provide students with an intense introduction to contemporary art practices. Students are encouraged to think outside of the traditional dimensional and disciplinary frameworks to create work rooted in original concepts, rather than the medium of the work. The four faculty members collaborate with each other to create assignments that are intended to balance the conceptual and technical development of their students.

The school, much like the art world, is not easy on newcomers, but it reflects the liberating yet harsh reality: “The possibilities are endless.” Students who come in with the intent to pursue a particular medium are required to experiment in different media while taking 15-18 credits their first semester, leaving little time to the kind of work they intended to do when they enrolled. In a survey of 70 FYP students taken in November of 2004, 60% agreed that students should be required to learn how to work in a variety of media, while 31% wanted to work in the media of their choice. In response to students’ wish to get more involved in a particular medium, each department offers introductory courses called Contemporary Practices, which students can take once they have completed the core studio requirements. However, one participant in November’s survey complained, “I had to waste money on taking 18 credit hours on classes that didn’t apply to my major.” Jennifer Kramer, a FYP student in the spring of 2005 said, “My main area of interest is in painting and drawing … I am glad the FYP is structured so that I can try out different mediums and techniques. I think that getting my feet wet in different types of art will help improve the way I approach my 2-D work, but I’m getting a little antsy because I haven’t had time to sit down and paint for the last couple of months.”

The conceptual framework directs the experimentation that happens in the Core Studio. Students are asked to talk about their work, explaining the formal solutions they applied to a particular idea they had in mind when creating the piece. However, the large class size (60 or more students) hinders the quality of critiques, according to Adjunct Associate professor Gordon Powell. He said that students became disengaged as the critiques progressed. His team tried to split the large group of students into smaller groups, but students were not receiving the full benefit of a critique from four different faculty members and the larger class. He also said that the large class size did not allow him to get to know the students and their particular concerns as well as he would have liked.

2004 was the first year the new FYP was implemented, and growing pains are to be expected. Next year, according to Jim Elniski, Associate Professor, Director of the First Year Program, the Core Studio class size will be cut to 45 instead of 60 students, split among three faculty members. Each instructor will be assigned 15 students and the groups will rotate between faculty during the semester. Powell mentioned that although teaching this year was a challenge, he looked forward to learning from the faculty he was teaching with. Although his work is primarily sculptural, he wanted to learn from faculty whose work was time-based. However, the current collaborative teaching arrangement, as well as a large class size, made the process of teaching “much more complicated,” resulting in “endless meeting and constant adjustments.” Powell taught 3-D studio in the previous FYP and said that he had to work a lot harder this year, meeting with other faculty before class and constantly revising the curriculum, a situation that sometimes proved frustrating.

Elniski admitted that the 60-student model did not prove to be sustainable, partly becasue of resource allocation. In some cases, it was impossible to provide enough equipment to 60 students at once. He said the FYP program was moving in the right direction, and the reduced class size will make the program more sustainable. It will provide “discipline in the interdisciplinary context,” while fostering “a greater sense of community between students and teachers.”

SAIC’s resolve to adjust its curriculum to remain “the most influential art school” results in hard choices for its students. Those who come expecting a more traditional, streamlined education will feel uncomfortable. The school expects the incoming students to be open to the various possibilities of art making. However, many undergrads make the choice to come to SAIC just because of the school’s position in the U.S. News and World Report Rankings that asks the deans of art schools to rank all other schools except their own. The report does not even rank undergraduate programs.

May 2005