In Their Own Words

Jessica Abel

Did you read comics as a kid?

From my earliest moments, I remember being interested in drawn images to the near-exclusion of photographic ones. When I was a little kid, my best friend Kristin’s family had a small boat that they kept at a marina in Michigan. I used to go up there with them occasionally to spend the weekend. The four-hour car ride was nearly interminable to my seven-year-old self, and, to keep us happy, Kristin’s mom would buy us each a three-pack of comics at a gas station near the beginning of the trip. They used to sell comics this way at gas stations: sealed-in-a-plastic-bag three packs of kids’ comics, like Richie Rich and Casper. Anyway, the only problem with this cushy arrangement is that I read them all in an hour or so, and then had to spend the rest of the trip wishing we had more and whining “are we there yet?!”

At the time, I thought it was pretty rebellious and “punk” to be a girl and yet reading comics. My interest grew and a gift from my dad of some Ms. Tree comics (a black-and-white mystery comic from First Comics) scripted by one of his clients helped me start to seek out more black-and-white titles and whatever seemed interesting. I was pretty lost in a comics store at that point, though, and didn’t have much of a clue what I liked. I also didn’t know anyone else who read comics, so didn’t have anyone to talk to about it. Soon after I arrived at college in 1987, I stumbled across Love and Rockets #21 in a local record/comic store, and it made a huge impression on me. That comic was a new beginning.

Are your comics feminist?

I am an ardent and declared feminist, not afraid of the label, but I simply allow my view of the world to inform my writing, not dictate it. My comics are implicitly feminist (because I am), but not explicitly so (because that’s not what I’m interested in writing about). Why aren’t men asked this question?!

Is the comics world sexist? I can only speak for the “alternative” comics end of things, but my experience has been: implicitly perhaps, but not explicitly so. No one has ever told me that they aren’t interested in publishing/carrying/selling/buying my work because I’m female, but, then again, there are quite a few female comics artists I know or know of, and I don’t see their work represented as well as they ought to be, but, then again, I have no idea. Maybe there just aren’t enough of us. We do get asked stupid questions like this one, though. As to the “mainstream” comics world, yes, to my knowledge it is sexist, though it seems to be so mostly on the readership side, not the editorial side, but I don’t have that much to do with it, so don’t quote me on that.

Do you feel comics are a “fine art”?

Of course [comics are a “fine art”], but it’s a lot more akin to film and literature than to painting and sculpture, thus probably won’t be on the walls of museums much, but it doesn’t really belong there. You can’t really “get” comics without reading them, and that’s not an activity that is easier and more pleasant by squinting at a wall. Anyone who [thinks] that putting words and pictures together somehow makes them less expressive and less interesting, is really not thinking clearly. The suggestion that this might be the case is not only insulting, it’s nonsensical. I’ve heard it all my life, and every time I do, it sounds more reactionary and sillier.

How did you get started in comics?

Born in 1974 and raised in Denver, I moved to Chicago when I was 18 to attend SAIC, then to Austin two or three years after graduating, where I still currently live and make work.

In middle school, I made my own comics and xeroxed them and sold them (to great thrill!) at a Mile High Comics franchise shop in a small strip mall by my parent’s house. I remember the dumbest one, called “AFTERDEATH,” which was a story about nuclear war survivors, which I drew during math class with my friend Tim, pretty much populating the whole thing with robots, explosions and a struggling inability to draw women’s breasts in any lifelike proportions. We sold 46 copies, they’re out there somewhere–haunting me.

What are you working on now?

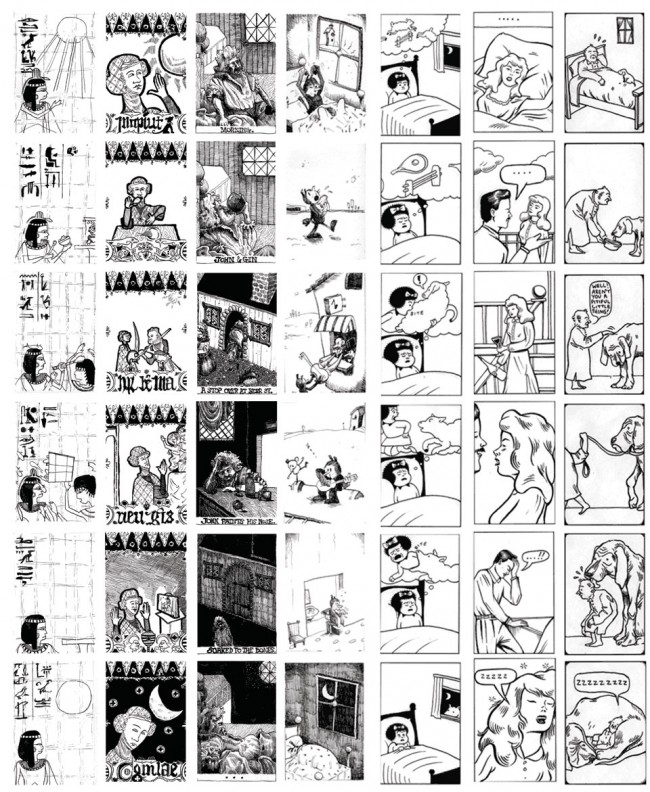

My website, www.ep.tc , has been my longest creative project. I started it in 1993. The Internet was SO SLOW back then. As the web got quicker, I started adding stuff to it, including midi file versions of sound work, essays, reviews, etc. It became a zine to me, and the closest thing to a representation of myself to others. I just continued adding to it, and taking away from it, as time went on. The most notable item I have there right now is a completely unknown, incredibly elaborate comic from 1957 on the birth of Atomic Energy. I also have a comic posted on heroin addiction in New York, from 1966. Both were previously unheard of, I’m proud to say.

Can you tell us about your current projects?

As for stories I have on my website: TEDDY is about an unfixable love affair between two young people, based in Chicago ten years ago, told simultaneously with four comic characters of mine named Teddy, Girl, Clod and Clown. Actually, many people tell me this particular comic is very difficult to describe, so you should just read it yourself. I think it’s one of the best things I’ll ever make, though. It works for me like a photograph does for other people. I’m happy to say a lot of people seem to take value from it, too, which matters a lot to me. A DOG AND HIS ELEPHANT is more of an actual drama, scripted out like a play, self-contained in a single room where the camera angle on the characters never changes. Kind of like having a webcamera on someone and them not knowing it. It’s very difficult reading at points, dealing with an abusive trapped relationship.

Do you think comics are a “fine art”?

I think it’s an outdated myth that comics aren’t already considered a major and highly powerful means of art-making. It’s certainly capable of ripping film in half as the most powerful pop-cultural means of telling a story. As a means of self-expression, few acts of labor and design can beat drawing the damn things, too.

The larger issue isn’t the art world embracing comics as an art form, so much as the comics community embracing art as a concept. There’s a lot of antagonism, particularly with the readership. I’m much more familiar with comics-people having outright judgemental and hostile feelings towards the art world and viewing most art as bullshit than the art world viewing comics as marginal. I’m much more on the side of art here, and I feel a lot of comics makers are creative prudes, and their audience is a trainwreck, too. That’s changing, though, fortunately. There are a lot of comics right now that are absolute pieces of art, and are very much made my art-minded people, making the work because they need to and for no other reason.

Comics are cheap to make. They’re also extremely fun to do. The only gamble is they take a long time to get good at. But you’re given complete creative control of them and you work to make a reproduction. The art object is the reproduction, so people can own your work at their home and not have to visit somewhere (a gallery or a theatre) to experience and enjoy it. Also, the language and history of the medium is fascinating and rich–as old as vaudeville. Many people have noted that the only three American art forms are Jazz, Film and Comics.

Scott Marshall

How were you involved with the School of the Art Institute?

Born in Chicago, I spent my first 20 years in Skokie, Illinois. Ever since earliest childhood I always knew I wanted to devote my life to visual art and music. In 1992, I had an interview with an admissions counselor at SAIC. I discovered I had 60+ credits that would still be accepted from my laughable first attempt at college. I applied to SAIC, and to my amazement, I was accepted and given a small scholarship. The funny thing about SAIC was that I had gone there for representational painting, yet was pretty snubbed by the painting department which looked at me like an alien or a low-grade moron for wanting to paint narratively. I spent two years at “F [Newsmagazine],” the second year I was the Art Director of the paper.

What are you working on now?

I thank my old “F” comrade and friend Ethan Persoff for getting me involved in the recent Fantagraphics book about the evil scum in the Bush Junta. For these poltical cartoons, all I have to do is watch or read the news and get instantly outraged at the murderous lies, deceit, and fascist tactics of the Bush war criminals. [I’m working on] a new political cartoon and animated video project with Ethan Persoff, some new paintings, and a forthcoming short film with my regular collaborator, choreographer Scott Rink, for which I provided the soundscape and audio collage (a 20-minute dance narrative based on an early Ray Bradbury short story).

What advice do you have for prospective young comic artists?

If you want to be as unique as possible, do that one thing and do it ad nauseum. Then, just keep sending it around and promoting it whenever and wherever possible. Self-publish if you have to. For instance, I love Chris Ware’s stuff, and he’s a really nice guy too. He was a couple of years ahead of me at SAIC. One day in a printmaking class at SAIC, I was rummaging around in the scraps of small litho stones, and found a small stone buried in the back that still had a four-panel Ware cartoon drawn onto the surface. At that moment, I realized why he’s so darn good–because that’s pretty much all he’s ever done!

On the other hand, if a student wants to break into big-budget animation or publications, then they would do well to emulate an existing commercial style, do it to perfection, and then try to get an internship at a targeted studio.

What else are you interested in?

I’m not happy unless I am working on one of my creative projects (drawings, paintings, music, audio collage, etc.) Otherwise, I’m a bit of a recluse (much to my wife’s annoyance) and keep in touch with all my far-flung friends with lots of e-mail. I also am a big fan of cinema and watch a lot of movies.

Do you think comics are “fine art”?

If there is one lesson that was learned (often the hard way) from the paradigm-shift between Modernism and Postmodernism it is that A_N_Y_T_H_I_N_G can be considered “fine” art. And I’m not talking about numbskull poseurs like Damien Hirst or Jean-Michel Basquiat (the former a true postmodern charlatan, the latter a drug-addled Nouvelle Retard). When I think of the comic form raised to High Art, with a capital “A,” I think of Peter Saul or Oyvind Fahlstrom or late Phillip Guston. And then why stop there? You can also include Red Grooms, Saul Steinberg, Sue Coe, and Ralph Steadman. The list goes on and on. Hell, you can say that even some anonymous Roman-era wall-fresco cartoons or 18th-century Hogarth illustrations, or, certainly, Goya’s “Los Caprichos” should be included as well. Short answer: yes; as it always has been, so shall it always be.

March 2005

Some of these cartoons were simply weird looking, the characters featured by Ethan Persoff that look like burn victims! Now, I realize he did these as a brain addled school boy so he gets a break…