A (Nearly) Lost Art

Illustration by Megan Pryce

From massive highway billboards to boutique storefronts, signs are part of any community. We may see hand-painted letterforms nearly every day, but few of us give them much consideration, let alone appreciation. But, for the artists behind many of the signs we encounter, a combination of their lettering artisanship with a nearly 150-year history of the craft is informing a growing fascination with sign painting and the typographic arts.

“We build letters,” says Jeff Williams, a Northern Illinois-based sign painter who also practices gold leaf and vehicle lettering, in an interview with F Newsmagazine. “I’m still fascinated by that, even after all of my time doing it.” With Chicago area-based colleagues Bob Behounek and Pat Finley, Williams has been working since the 1960s, hand painting everything from show cards to race cars.

Left to right: sign painters Pat Finley and Jeff Williams, Sign Painters co-producer Sam Macon. Photo courtesy of Jeff Williams.

Sign painting is a truly American art form. Beginning in the late 19th century, sign painters were the original advertisers, transforming symbols from their original purpose of identification (what was inside a building) into sales pitches (what was special about what was inside). Until as recently as the 1980s, sign painting was a common profession, but with the advent of computers and vinyl lettering machines, it has become a specialized trade. A great painter does not necessarily make a great sign painter; in art, the ego of the artist is at stake, and there is no right or wrong way to paint, but in signs, the ego of the client is at stake, and there is a clear agenda.

VICTORY OVER VINYL

Several sign painters saw their trade take a significant step into the public eye after the release of Sign Painters in 2013. First a book, then a nationally-screened documentary, Sign Painters is a project by Milwaukee-based artist, photographer, filmmaker and curator Faythe Levine and Chicago-based filmmaker, photographer and writer Sam Macon. They highlight the work of two dozen artists working across the U.S. amidst an overview of the craft’s history and near extinction with the onset of digital design.

Behounek, Williams and Finley participate in charity auctions through Chicago Brushmasters, painting automobiles and other items to raise money, but they say that Levine and Macon’s film has provided a new outlet for informing others about their work. “The auctions are one way to keep this trade and all of these handcrafted art forms in front of the public eye,” Behounek explains. “Before Sign Painters, that was all we had, but now that movie has told the general public that we’re still around.”

A sign by Bob Behounek. All photographs courtesy of the artists.

A chair painted by Bob Behounek

A sign painted by Bob Behounek

Levine got in touch with Behounek after seeing one of his colleagues pinstripe a motorcycle at a Harley Davidson event in Milwaukee. “I honestly thought that nothing was going to come out of it,” Behounek says. “We’ve been doing this for how many years, and no one had ever given a care. But she and [Macon] were right on and diligent.” Williams met Macon at the Sign Painters book launch in Milwaukee, and they collaborated, along with Finley, on scenes for the film that document the process of painting signs, to supplement interviews and historical footage.

Truck painting by Pat Finley

Truck painting by Pat Finley

Sign painting by Pat Finley

Sign Painters addresses the demand for hand-painted work and a recent surge of interest in typography: the difference between “typeface” and “lettering” (lettering implies drawing, while a typeface is a mutable group of letterforms that work together as a system) and that sign painting is the opposite of fast, quick and cheap production. Several of the artists featured say they feel American culture, as a whole, is being aesthetically dumbed down as quality dives and the notion of craft continues to be discarded in favor of speed. Others speak to a steadily growing demand for authentic, handmade items, part of a nostalgia involving re-discovering older technology in new forms.

“If the film is going to do anything, it will bring in new, fresh artists to the trade, people that have never seen sign painting before,” Behounek says. “You can assume that anyone under 40 years old hasn’t ever seen a sign painter paint anything, anywhere. The movie has definitely opened up avenues for younger people.”

“Designers are now realizing that if they can bring in some hand-drawn artwork to what they do, they’ll have an advantage over others who are only using computers,” says Williams. “They’re taking a step backwards to do what we’re doing, and they’re intrigued by people like us, from the old school, who are still out there.”

CITY OF BIG SIGNS

Stephen Monkemeier is a young Chicago sign painter with a background as an oil painter and graphic designer. He recently started his own sign shop after working for six years as a sign artist with Trader Joe’s stores in New York and Chicago. A colleague there got him interested in vintage techniques for handmade signs. “I don’t feel like I ever made the decision to become a professional sign painter,” he tells F Newsmagazine. “Once I knew it was something that I could do, I didn’t look back.”

Stephen Monkemeier. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

After his time in New York, where he found Levine and Macon’s Sign Painters blog, Monkemeier moved to Chicago and immersed himself in the local sign painting community. He connected with Stephen Reynolds, whom he credits as teaching him how to use a lettering quill as well as “how to deal with clients professionally, how to work faster, how to set up a workspace on any job site and most importantly, how to trust my own instincts rather than over-planning everything,” he says.

Sign painting by Stephen Monkemeier

Sign painting by Stephen Monkemeier

Sign painting by Stephen Monkemeier

The Chicago area is home to a number of active sign painters, including Behounek, Williams, Finley, Reynolds, Ches Perry, Robert Frese and Andrew and Kelsey McClellan of Heart & Bone Signs, among others. With its printing and publishing industries and its being a major American commercial hub, Chicago has historically been a powerhouse of advertising and typographic arts. Beginning with the work of Frank Atkinson, who published several sign lettering manuals at the end of the 1800s, Chicago’s demand for innovative signage kept growing. In the 1940s a number of designers came to work for the Beverly Sign Company, which at its peak employed 50 full-time sign painters. Chicago is also home to the Sign and Display Artist’s Local Union 830, where Behounek trained under former Beverly employees; he is now a member and Apprentice Instructor.

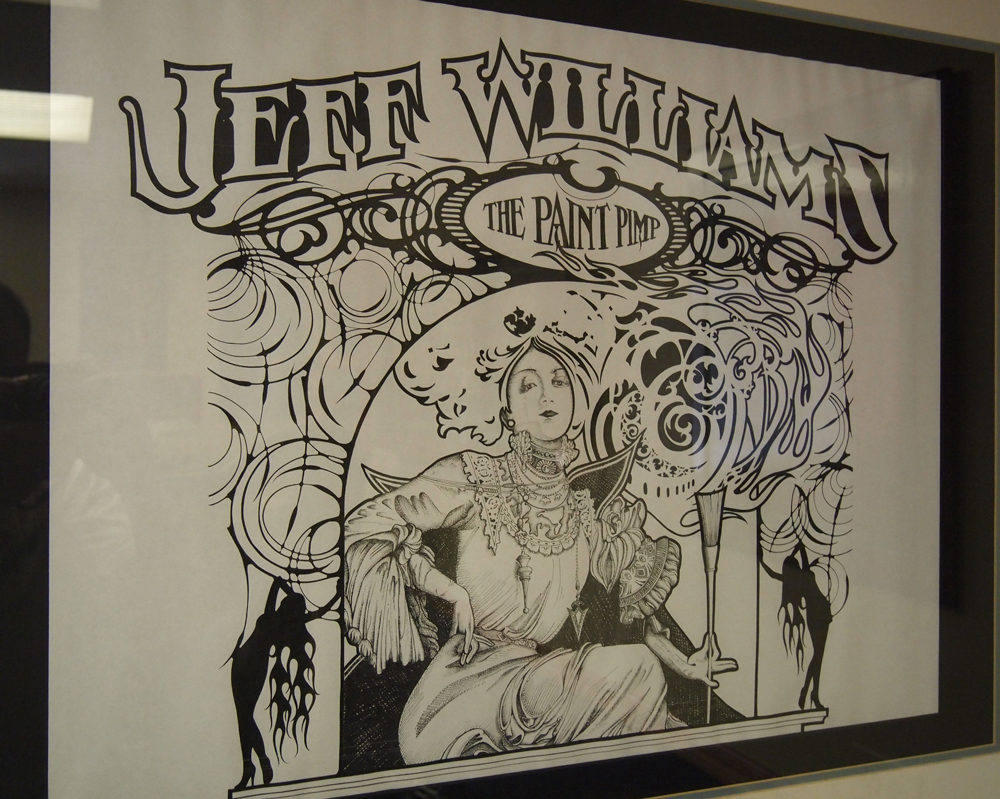

A window sign by Jeff Williams

Work by Jeff Williams

Sign painting by Jeff Williams

Beverly garnered national attention for their development of the avant-garde “Chicago Look,” a combination of pastel colors and panelization, as Finley explains. “You take a color-filled geometric shape and insert type into it, and then that breaks down the design into a few different signs, depending on size. That was unheard of before Beverly — those people were pioneers, and with everything they did, the world followed.” It attracted flocks of aspiring sign artists.

From sign painting’s roots in the city, a creative incubator continues to grow. “Being a part of the community is my favorite secondary characteristic of sign painting. Compared to New York, it’s been really fun and easy in Chicago to meet other design aficionados and artists. People aren’t as exclusive,” Monkemeier says. “It’s also a much easier city to live in, so I actually have time to pursue my interests.”

Behounek feels that the key to keeping the craft alive is openness and a greater sense of community. “Sign painters have traditionally been known to be secretive, and one of our downfalls is probably not divulging information about technique,” he explains. “But if we didn’t share information with other painters, the trade would never progress. No one would learn, and there would be no inspiration.” This sharing, especially of the finer details, is essential. “It’s not the big things, it’s the little things that need to be passed on,” Finley says. “Like, how many drops of silver you put into white paint to make it shimmer, or how to trim the edge of a striping brush.”

DRAW TYPE AND MAKE FRIENDS

Sign painters, despite their varied talents and styles, are linked by drive, dedication and passion; while the trade is based on apprenticeship-style learning, it takes time and commitment to process. “We tell aspiring artists that they need to practice at least eight to ten hours a day, six days a week, for about five to ten years to even get the basics down and get halfway good. Then you’re ready to start your own style,” Behounek says. “You need a conscious effort of the foundations of lettering. Start with perfecting Franklin Gothic, and draw type until your fingers bleed.”

But mentors along the journey are increasingly hard to find. There are not enough sign painters now, Finley notes, and “as much as I’d love to teach someone, I couldn’t afford to pay them for helping me out.”

Plus, as Williams says, aspiring sign painters often lack an understanding of how much work it takes to gain the skills. “People don’t want to just practice drawing block letters; they want to get to the fancy, fun stuff. If you can’t hold back and take it slow, you’re not going to make it as a sign painter.”

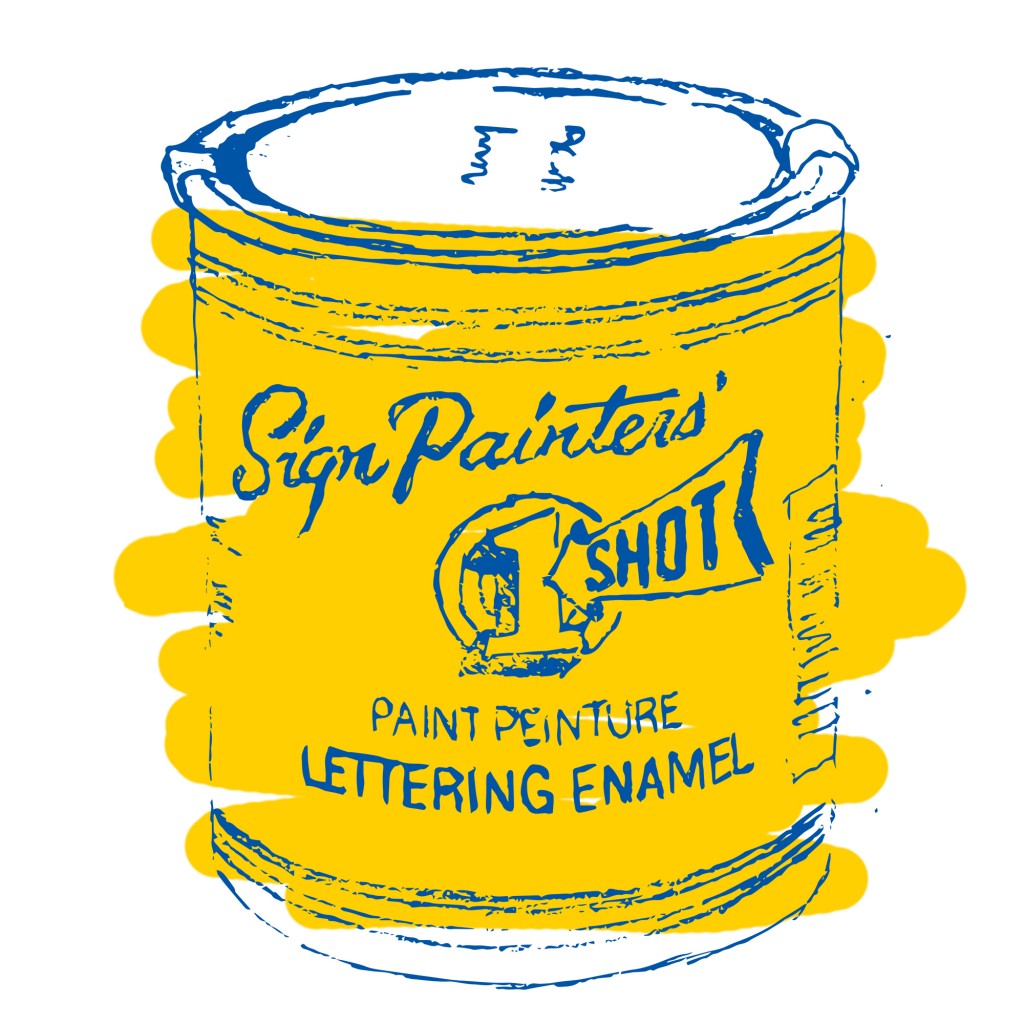

Behounek suggests that young sign painters find the work of lettering artists that they admire and try to emulate their work. Or make trips to the grocery store. “You can learn a lot through packaging design, newspaper design, anything that has any kind of advertising on it. Just like Andy Warhol, go down the cereal and candy aisles! Look at all of the different possibilities for color and type combinations.”

Monkemeier’s advice is simply to practice and to get as much creative input as possible. “Be original! Know the difference between following the rules and ripping someone off,” he says. But most important is patience. As if considering the very future of sign painting, he remarks, “Put in the effort and it will pay off.”

Jessica Barrett Sattell is an MA candidate in New Arts Journalism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She writes about the intersections between design and community and likes monospaced sans-serif typefaces (especially Letter Gothic).