Still life paintings are one of those aesthetic practices avoided by a majority of artists due to their stateliness. A vase, a bowl of fruit; a dinner table with disheveled place settings, all rendered gorgeously in their silence, as if a spotlight were thrown on them for investigation. In modernity, their technical mastery is offset by courtly images of Old Masters operating within a closed system. In their function of the elite recording itself, perhaps portraiture is the only genre rivaling it.

However, unlike portraiture — which has seen a revival in recent years due to an increased desire for more diverse representation in media — the still life remains on hard times. It’s more difficult to implicate broader significance in a flower bouquet than in an undocumented immigrant or an unarmed black person killed by police. As a concept, the still life requires a sincerity in application, and an appreciation of surface images that “the demands of the times” are justifiably losing patience for.

In the words of Susan Sontag, style is a means of insisting on something. “Still Moments,” the closing exhibition at Matthew Rachman Gallery, manages to combine two unique yet thoroughly accomplished artists emphasizing the bracing and fleeting nature of memory.

___

Tom Judd, who’s currently based in Philadelphia, lived in a modernist home in Mount Olympus, UT, as a child. At the age of six, his family moved to the suburbs of Chicago for a year. In interviews, he’s described this experience as traumatic, and his affinity for painting modernist structures functions simultaneously as a preservation and an inquiry into whether or not anything can be preserved — a monument on shaky ground.

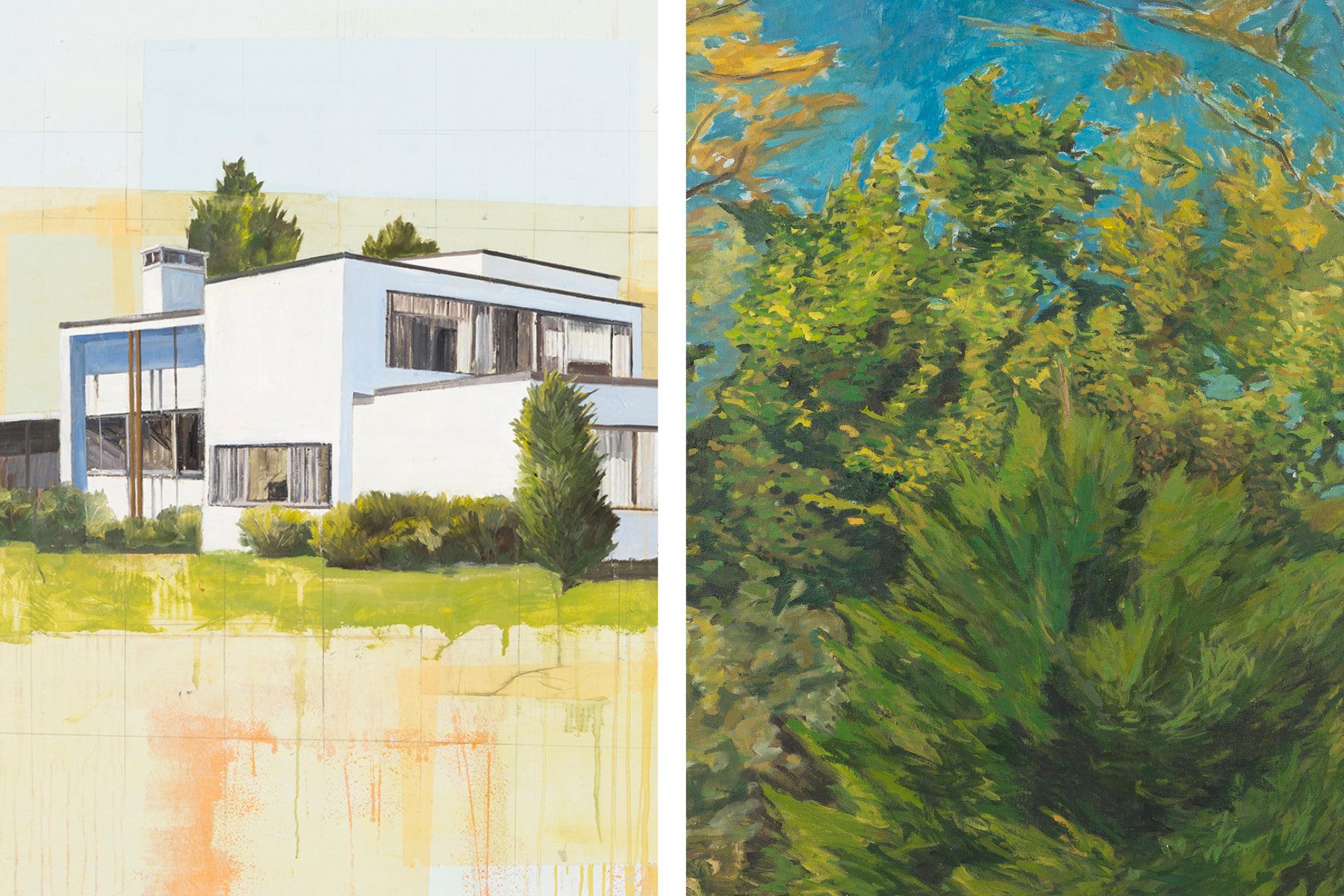

In fact, the houses are the only thing Judd seems sure about; in “Neutra,” skies are rendered through light blue brush strokes failing to saturate the entirety of upper parts of Judd’s composition, while in “Breuer #4” and “Mouro,” the texture of grass and foliage is achieved through sharp strokes and insistent pressings, or barely scraping green across the foreground. (Clay and rock formations are achieved similarly, in pale pinks and shadowy grays.)

Clearly, effort has been put into constructing these scenes, but in a manner that doesn’t call to mind exactitude or surety. The efficiency of their construction gestures towards getting the approximate details right, rather than remembering every pebble or counting every branch on a tree. However, in all of Judd’s paintings, the houses are drawn precisely, with clean lines and dense saturations establishing their solidity.

At least until the paint drips down the rest of the canvas. Outside of how environments are rendered, Judd’s paintings also challenge still life forms through showing the skeletons of their conceptualization. Numbered grids, resembling blueprints, are the speculative outlines on which images are constructed. Judd’s signature, the dates of the paintings, and his notes are scattered throughout the composition’s edges. Combined with the fleeting nature of the environment around the houses, the paintings are profoundly speculative; in a sense, one isn’t sure of where imagination ends and where physical forms, existing in the world, begin. However, another way to look at it is that the line is so porous that it’s impossible for imagination and physicality to remain in their respective camps. Perhaps this is best evinced by “Farnsworth House,” a black and white piece whose black surface resembles a night sky, with chalky grid lines calling to mind constellations of stars.

___

Similar to Tom Judd’s fixation on houses, Slater Sousley, who received his BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), appears committed to rendering woodsy, outdoor scenes. The comparisons end there: Whereas Judd uses his gifts to render metaphysical movement, Sousley’s interests lie in the physical. His paintings, at first glance, have the appearance of camouflage, built with smudges and smeared brushstrokes of paint. This is part of their game though, their grandeur. Through a precise juxtaposition of concrete and abstract structures, Sousley captures the feeling of stumbling through nature’s expanse.

The vantage point is always close up; the images, a little out of focus. Angular bursts and slashes cut throughout like branches blown in the wind. The reach of trees and bushes is overwhelming, until — as in “The Woods Beckon” — you come across a gargantuan tree trunk. Solidity. Relief. Another whorl of autumnal browns and greens (“Overgrowth on the Bank”), until you’re overtaken by “Treetops,” an angular spray of fir needles crowding the wobbly space of birches and oaks.

Precision versus expression is a classic artistic consideration — a conundrum of which still life painting possesses a large stake. It’s a testament to Sousley’s technical acuity that he’s able to deftly traverse the ground in between. How else to explain “November Brush,” a green-and-cream painting, with streaks of brown and shadowy purples coming together to form a bush we’ve stooped down to examine, other than to say that he precisely expresses experience?

___

Outside of revitalizing still life painting, the exhibit was doubly impressive due to the youth of its curator. Still Moments is the first exhibition organized by Martha Morimoto, who also received her BFA from SAIC. She deserves a great deal of praise for her thoughtful and elucidating work, as well as a coterie of eyes on the lookout for her future projects.