We respond to faces. In conversation, we watch each other’s eyes or the positioning of the head for cues. It is other people with whom we are often most preoccupied, and who can both inspire an artist to paint a likeness and entice a beholder to ignore the artifice of that likeness, making portraiture perhaps unique among artistic traditions. As portrait artist Gwenn Seemel has pointed out, when someone says “my portrait,” they usually mean it is of them, not by them, implying that here the work is less important than the subject.

“There is great difficulty in thinking about pictures, even portraits by great artists, as art and not thinking about them primarily as something else, the person represented,” writes Author Richard Brilliant in his book “Portraiture.” This seems to assume that an effective likeness cannot be created without the personhood that goes along with a face. But, need a subject be real to make a good portrait? At Roman Susan Gallery six Minneapolis artists offered answers.

The exhibition “Portraits” depicted fictional individuals. Though the works were from different artists, the people they represent seemed all to be residents of the same place. Their features distorted, highly conceptualized or masked, they represented the denizens of a village manufactured by a single mind, in this case one shared by several people.

It may simply be that the artists are also close to one another, as in the collaborative paintings of Andrew Mazorol and Tynan Kerr, or the father/daughter team of six-year-old Dakota Temte and Dylan Alverson. And all of the artists are friends. Unintentionally, they have depicted creatures that seem to come from the same place: a Blakeian universe, in places bubbling sinister on the surface, but everywhere a foundation of sincerity, conviction and even sweetness is a scratch below. The exception was four portraits by Colin Marx, in which the faces have been removed to reveal the terrific void of soullessness — these are the villains.

Other inhabitants were Temte and Alverson’s schoolgirl and middle-aged man as well as their authority figure, perhaps the ultimate: Jesus or an art teacher. Mazorol and Kerr who work only together sometimes paint over each other’s work on the same piece. Are the arguments they claim to often have in their studio over which aspects of their aristocratic figures to preserve? Or, about whether their subjects’ faces should be masked? Are they masked?

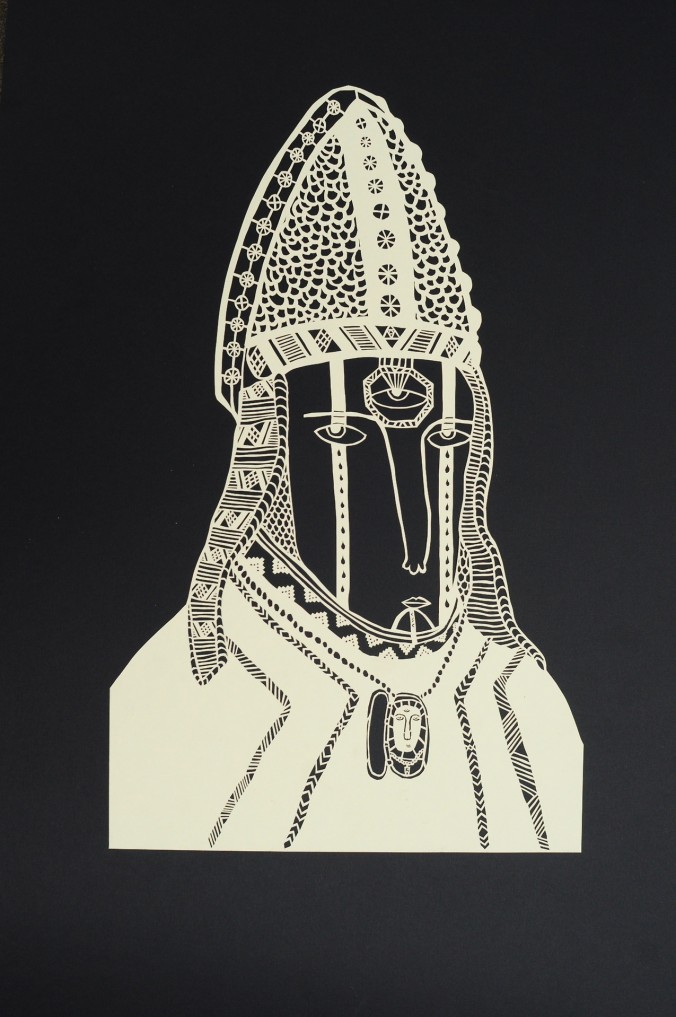

We are used to seeing a portrait and being interested in the subjects because we believe they’re real. But, though we know the subjects in “Portraits” were not real, we could take almost the same interest in them because the figures depicted were directly related to these artists’ collective interpretation of the world. The incredible detail of artist Christopher Saint Christopher’s amphetamine paper cut-outs are breathtaking in their exactitude and scale. The tedium of their creation makes his subjects powerful figures in their world, and the details do not distract from the grave, judgmental countenance of his priest in vestments nor from the grace and mystery of his bearded mystic.

Lauren Roche, whose portraiture was effective in the forgettable-ness of its subject matter, did the work of populating the world these artists share with ordinary people. In her contribution of six works, the figures were dark, rich and personal, with shadowy backgrounds and small red flares in a headscarf or pair of painted lips. In these portraits, Roche established a taxonomy, in which can be seen the fashions of the time and the genome of the people.

In his book, Brilliant discusses how portraiture changes when the perceived nature of the individual in society changes — who is important to immortalize at a given time, who is influential enough to command a portrait and what the very definition of individual importance is. In “Portraits,” the artists instead embraced the power of the transaction between the players in the genre by questioning whether one of them even need exist.