Any show centered on work by students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) is bound to touch on a wide variety of global and national issues, simply because of the cultural diversity in the student body. However, the Low-Residency MFA Show, on view at the Sullivan Galleries from July 11 to 28, emphasizes this more, likely because of the nature of this particular graduate program. Most SAIC students, although they hail from all around the world, live, share experiences, and grow artistically within Chicago. Low-Res students, on the other hand, complete their program remotely, living and working elsewhere for most of the year and congregating at the school for three consecutive summers.

For their final summer at school, the 23 participating artists that form this year’s Low-Res MFA graduating class put together an exhibition that not only showcases their geographic origins, but also their identities as they are shaped by place. This is most evident in “1991-2019,” a piece by Meagan Cope consisting of a series of small floor plan models that, per the wall text, are “constructed from memory for every place the artist has lived.” The models, like the different buildings the artist has lived in, vary in size and shape; a two-floored house with multiple rooms follows a simple studio apartment. But they all have one thing in common: The walls are all transparent acrylic and the floors are all mirrors. Although painstakingly recreated from memory, it doesn’t matter where these rooms actually are. They’re anyone’s journey.

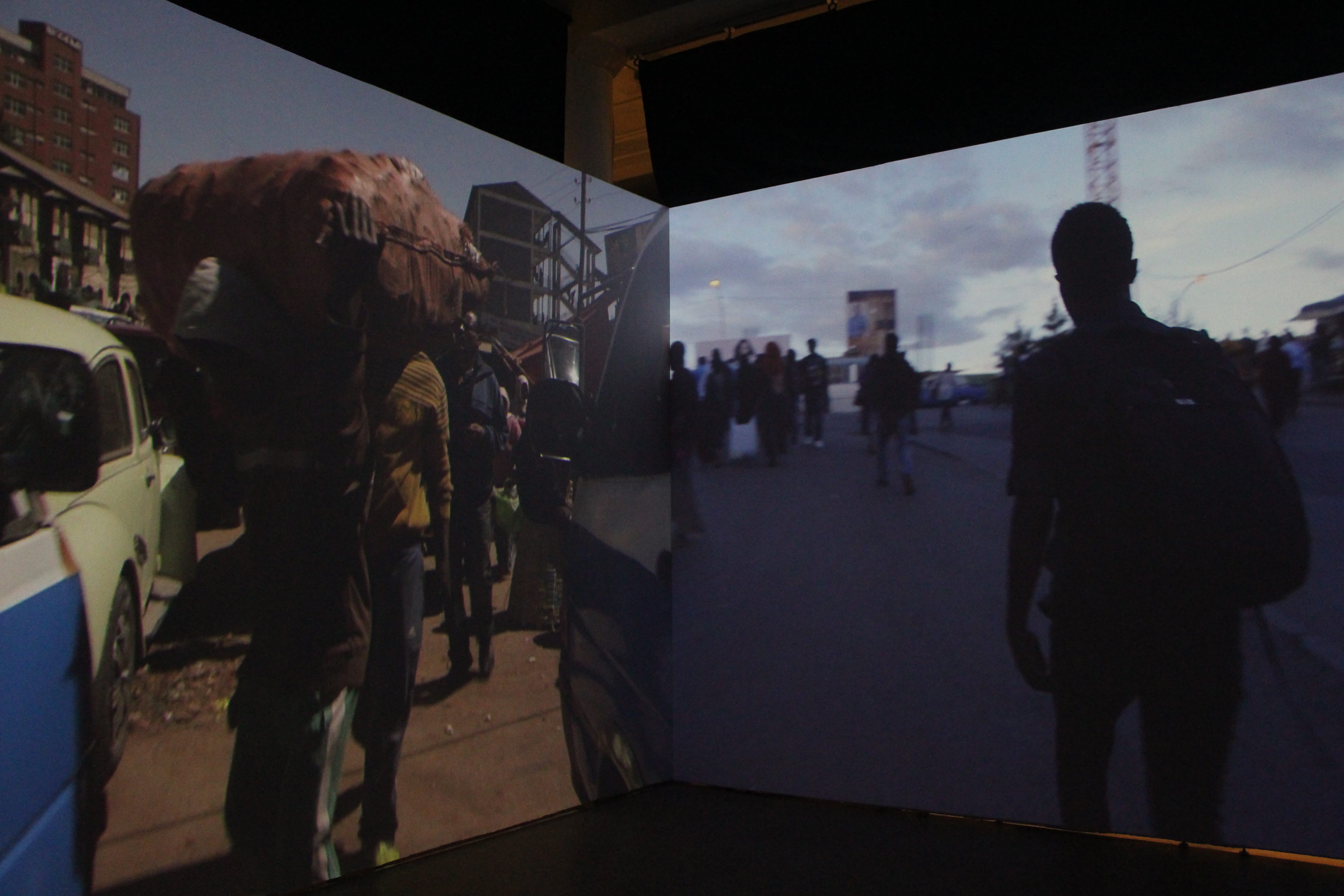

Identity defined by travel is a key factor in more of the show’s pieces, such as Lucas Habte’s video “Back To You,” a looping video with two alternating channels, each projected on a different wall. While the left channel shows a person in Paris overlooking the Louvre’s glass pyramid, the right one follows someone along a busy street in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The left shot remains on screen as the other cuts to black and then goes to another location. Then that one remains, and the left one switches. The two channels take turns showing an open field, a tranquil shore, and a loud nightclub, making the video feel endless. This mind, the piece shows, is constantly in two places at once, circulating between locations with no observable beginning or end.

While Habte’s piece invites the viewer to multiple locations around the world, Betelhem Makonnen’s work turns the camera, literally, back to the artist. Makonnen’s “selfing studies,” while simple in idea and execution, give a new perspective on selfies. The artist’s portrait and a picture of her taking a selfie are both printed on clear film, wrapped cylindrically, and placed on a reflective cardboard surface, amplifying the images in an almost kaleidoscopic output. In an exhibition full of works that explore the concept of self and place, these “selfing studies” accomplish an entirely different presentation of the idea of being everywhere at the same time.

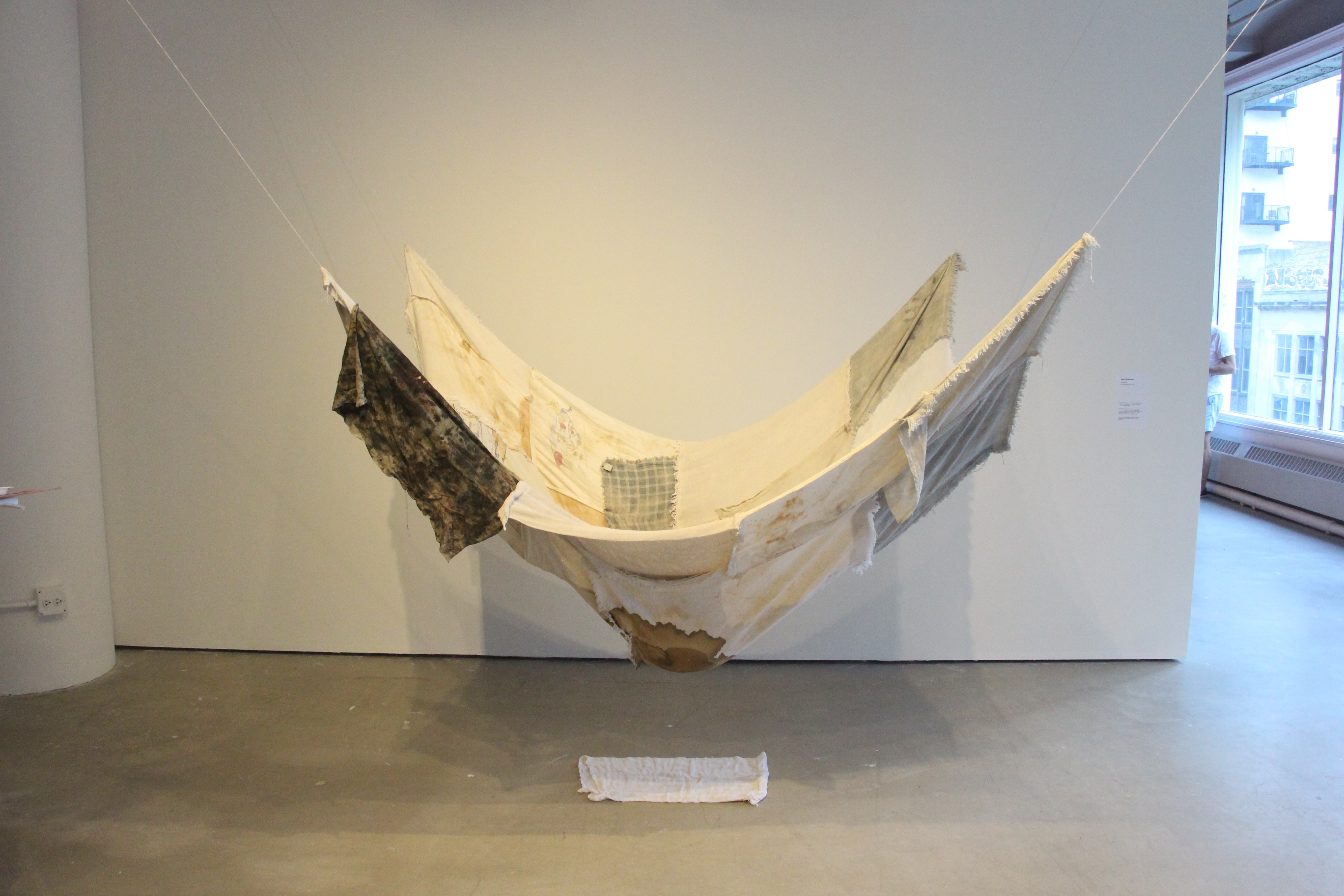

Another essential way the show evokes the idea of place is through the use of materials, and nowhere in the galleries is this more explicit than in Daniel Sacramento’s piece “Stain.” The installation consists of a number of used rags sewn together into a large, suspended rectangle, inside of which is a few pounds of ground coffee. Underneath it is another rag collecting water that drips from the top of the piece, which is essentially a massive coffee filter. Brazil, the wall text reads, was the country with the largest number of enslaved African people from the transatlantic slave trade, and many of them worked in coffee fields. It was also the last country in the Americas to abolish slavery; it was outlawed 131 years ago, in 1888. While simple in its composition, the piece is nonetheless powerful in its delivery, presenting an enlarged, grotesque version of a task as quotidian, yet historically charged, as brewing a cup of coffee.

Speaking of surprising material use, Ukiko Ueda’s installation “DELVE: Watts Bar” uses something guaranteed to make most viewers at least raise their eyebrows, if not outright squirm: earthworms. Inside a room covered with dark paint and an equally opaque curtain, the audience looks up to see several aligned transparent circles, each one of which holds a few specimens of worm in a petri dish-like arrangement. Lit from the top with red, green, and purple lighting, the room subtly combines beauty and uneasiness by giving the viewer a very particular type of vulnerability: the sensation of being looked at under a microscope.

As is the norm at most SAIC art shows, the exhibition has something for everyone. Next to pieces that offer the viewer several paragraphs of context are others that cede nothing more than the names of the author and the work. The first ones may be better suited to target specific issues that the artist touches on, usually critically. The latter ones, on the other hand, may appear daunting for audiences who prefer to be given a way into interpreting the piece, but may be perfect for those who prefer to absorb art primarily through its aesthetic, or who would rather understand the piece not through what the artist intended, but by how it may relate to the viewers’ own experiences.

In the end, this show felt different from the BFA and MFA shows at the end of the spring semester, each one showcasing work from hundreds of students. While it is understandable to show the work of all graduating students, these shows are inevitably challenging to viewers simply by the sheer amount of art exhibited. It’s a relief to return to the Sullivan Galleries to an exhibition with fewer works on display, allowing each artist to use more space and each viewer to enjoy looking at a less strenuous pace.