As an avid and obsessed fan of noir and neo-noir American films, I started watching Wong Kar Wai sometime at the start of this year at someone’s recommendation. I was blown away. The movie I watched was like a Quentin Tarantino film, except it was made earlier. The set of Hong Kong provided an exceptionally thrilling visual backdrop.

I started with with his softest work, “Chungking Express”; then I dug into his other less conventional films like “Fallen Angels” and “Happy Together.” Something about the green tones of the movie; the dark corners of the ragged rooms; and the sad, lonely characters appealed to me. Then I discovered the vast fan base that clamored over Wong’s films, and the existence of other East Asian filmmakers who were exploring similar themes of isolation in a fast, upbeat city. Of course, I had much prior exposure to Korean genre directors growing up in Korean culture as well.

There is no doubt that interest in East Asian filmmakers from the 1990s to early 2000s has been growing, developing a significant cult following over the years that now includes a large and expansive Western fanbase outside of the directors’ home countries. On websites like Fanpop you will come across various chains of discussions about Wong’s “peerless style” or his magical ability to “turn 22 seconds into eternity.”

The raw aesthetic and mood of the movies contrasts with the sleek, polished (and perhaps rigid) films in Hollywood. Maybe it is this “amateur” aesthetic of shaky, choppy, chase scenes and lonely and warped shots of eating in McDonalds restaurants at night that appeal to Wong’s following and younger generations. The familiarity or unfamiliarity with the settings and atmospheres of these films piques the interest of both Asian and Western audiences.

The international recognition of Wong Kar Wai, Chan Wook Park, and Tsai Ming Liang is probably only increasing as you read, so now may be a good time to get familiar with their work.

To start, the ambiguous narratives carry notes of longing alongside the desolate nature of the city. The troubled relationships and loneliness that characters often experience lead to an overall mood of heartbreak or apathy.

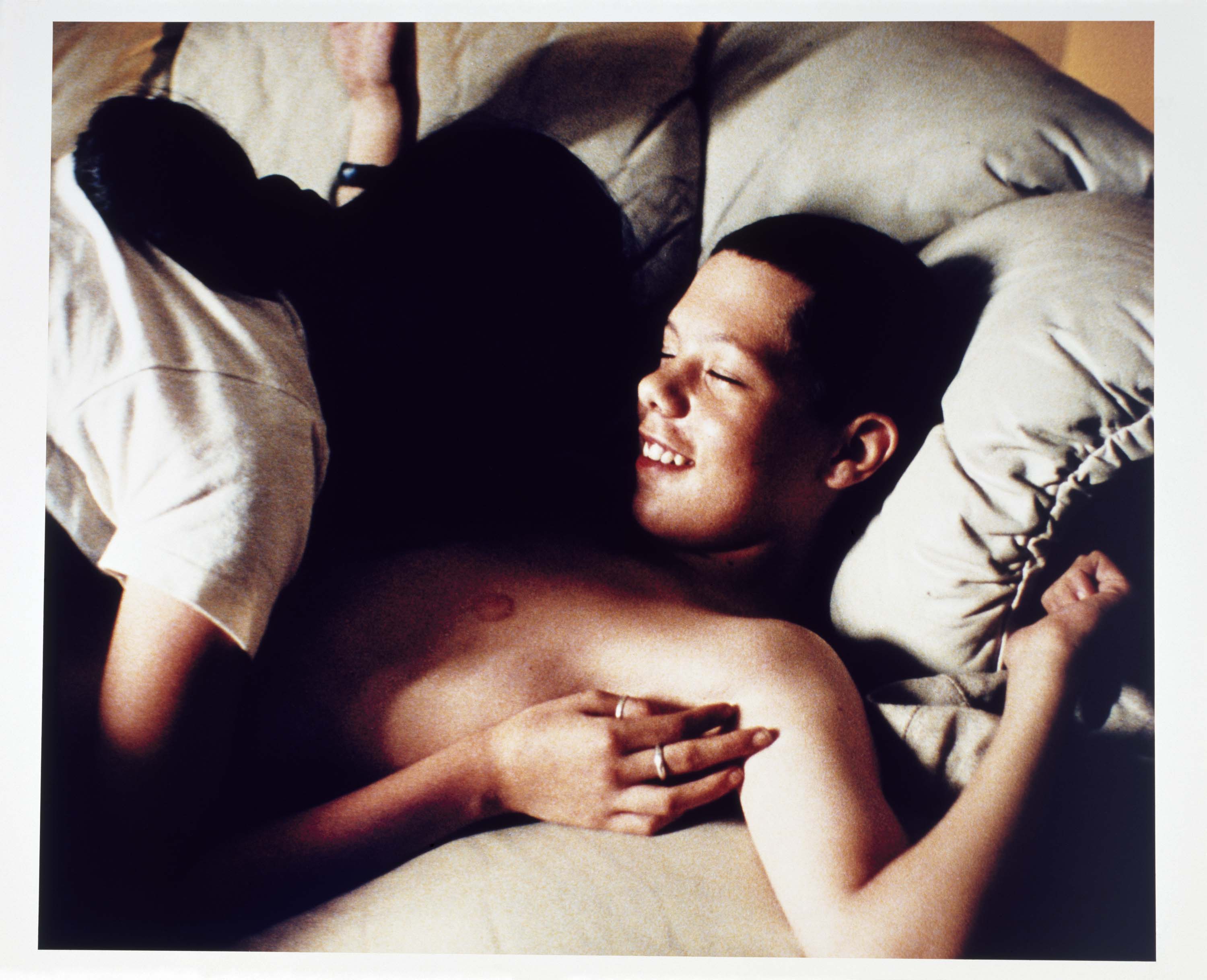

The visual appeal of the movies is strong. You find yourself staring at an excruciatingly long shot of a man devouring a cabbage painted as a head, then a 14-minute scene of the same man embracing his wife from the back. You might think it’s a still image, if not for the slight changes in expression as a subtle emotional tension builds. The stillness moves into a jarring sense of real time. Perhaps it’s the isolation of these characters that pull our sympathies towards them. They are financially and emotionally deprived. They wander and inhabit disappearing buildings and regions that are soon to be demolished.

In a way, these ‘80s to ‘90s settings of developing Asia, with all its flickering neon signs, grungy back alleys, and cheap motels, are documented as memories. They hold a certain familiarity, preserving fragments of the past. There’s a suggestion of time spent. The nuances of carefree youth become tangled in the atmosphere of the films.

During the past few years, international recognition of these directors has only increased. Their works have been showcased at various international film festivals such as the Locarno, Cannes, and Venice Film Festival. “Stray Dogs” won Tsai Ming-Liang the Grand Jury Prize at the 2013 Venice Film Festival. This indicates an increasingly positive reception of Asian films that are less conventional in style and narrative. Last year, Korean director Chan Wook Park’s “The Handmaiden” received the Vulcan Award from the Cannes Film Festival, and various awards for Best Foreign Language Film. Hong Sang Soo, also Korean and an alumnus of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), presented “By the Beach at Night.” The film won the leading actress Kim Min-Hee the Silver Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival. A Netflix-produced film called “Okja” is garnering a lot of attention as it prepares its premiere sometime this year. Bong Joon Ho — a celebrated Korean director who produced the Hollywood film, “The Snowpiercer” — directs the film. The trailer features Tilda Swinton among others.

There’s something edgy about these filmmakers. However, as Liang said in an interview, the works of East-Asian filmmakers cannot be defined under a single category. These films are unique precisely because of the different approaches that each director brings to the table. Every director experiments with different ways of telling a story, and with different visual techniques and narrative advancements. The films, ranging from super-banal realism to dark thrillers, are rich with color, cultural flavor, and a depth of character.

Currently, it’s unclear how long this enthusiasm will last. These filmmakers have been so overlooked in the past. Certainly, with the current political climate often retreating into hostile territories of racial ignorance, the future is foggy. However, these awards and cults around the Asian filmmakers are certainly improvements in the film industry that suggest a brighter future for diverse communities. These films have such a rich context to delve into, that they deserve every attention that is given to them.