By Joel Kuennen

By Joel Kuennen

“A chess game is

something very plastic.

You build it. It is a

mechanical sculpture,

with chess one creates

beautiful problems and this

beauty is made with the

head and the hands.”

—Marcel Duchamp

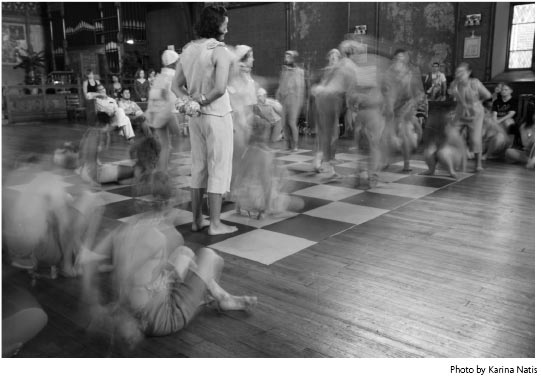

A linoleum chessboard sits in the middle of the darkened Betty Rymer Gallery. Strings of artificial stars hang down. Viewers are seated around the board, crowding back against the walls, watching an empty space. A tapping, then a clanging echoes down the hall outside. A master of ceremonies, sound and performance artist Sebastian Alvarez, strides majestically in, gonging a Himalayan bowl, and walks around the board to station himself in the back of the gallery.

The jingling march continues to be heard and sixteen pawns garbed in burlap masks and skimpy burlap shorts concordantly come in and take their positions—snarling and hissing at their respective opponents across the demarcated space. With greater pomp, the upper echelon of pieces arrives, all but the kings and queens. Finally, the kings and queens arrive, arm in arm; making the round of their garrisons, they take their spots. “One,” says choreographer Davy Bisaro, firmly. A pawn awakens, squirms, snarls and moves to its appointed position. The game has begun.

This is Anatomy is Destiny, a collaborative performance designed by Liliya Lifanova, which took place at the Rymer on September 11. Lifanova’s performance script enacts a game of chess played by Marcel Duchamp against himself as his female alter-ego Rrose Selavy. The performance reveals how in many ways chess was created as an abstract form to represent the grand narrative of life within its structure, battles, outcomes of win or loss.

Chess is dualistic, much as our culture has been conceived, the forces of light and darkness, good and evil battling for the win, so to speak. In Modern times (and beyond), an all-pervasive relativism has come to represent this binary dance. Yet relativism must remain dialectic, a conversation between poles of understanding that moves towards the relational. As any avid chess player will tell you, the joy of the game does not come from the recorded win or loss, but the road taken, and the conversation between the pieces. This dance reveals the fluidity of one’s position, how power shifts.

The costuming designed by Lifanova, with special attention paid to the positioning of each performer required by the garments themselves, not only signifies the role of the performer for the viewer, but makes us question what it is exactly that puts us in these positions to begin with. What determines our daily wins and losses? Every minute of everyday, snap-judgments concerning one’s roles are made, consciously or unconsciously, on the appearance of those who we meet in time and space. We try to discern as much as we can about the foe before us, visually comparing and classifying the sensory into categories of knowledge.

The costuming designed by Lifanova, with special attention paid to the positioning of each performer required by the garments themselves, not only signifies the role of the performer for the viewer, but makes us question what it is exactly that puts us in these positions to begin with. What determines our daily wins and losses? Every minute of everyday, snap-judgments concerning one’s roles are made, consciously or unconsciously, on the appearance of those who we meet in time and space. We try to discern as much as we can about the foe before us, visually comparing and classifying the sensory into categories of knowledge.

Anatomy is Destiny transforms the objective game into something that more closely resembles the metaphorical meaning of the game. It is within the interaction—the conversation—that the meaning of grand-metaphors becomes realized.

In her artistic statement, Lifanova explains: “When I study a transcript of a chess match between two players, within a short period of time I can see each person’s aggression, defense, victory, and defeat expressed through the language of the relational. In each game, a common narrative begins to emerge, a metaphor for the complex system of life itself expressed through the abstract and silent pursuit of the bottomless truth or the full acceptance of the absence of it and the continual re-creation of one gradually sculpted in time.”

If chess is a metaphor for the game of life, there is one fundamental difference. In chess, two entities collide in space and time and only one may occupy that space. It is the entity with the highest status that supersedes the other—sending one after another off the plane until the game is reset and the great dance in space and time is begun again. In life, the hope is that the rules can be broken, even while the over-arching system endures. As Foucault writes, using a different kind of match as metaphor, “In judo, the best answer to the opponent’s maneuver is never to step back, but to re-use it to your own advantage as a base for the next phase…Now it is our turn to reply.”