On July 20, 1969, 600 million people watched the Apollo 11 moon landing, but how many appreciated its significance in terms of surmounting what Neil Armstrong referred to as the “glitches?” Impediments, or variations on perfection, that’s the intuitive understanding of a glitch. Live radio technicians in the 1940s coined the phrase to indicate interruptions in transmission that were irreparable because they couldn’t be traced. They tended to be self-correcting. This definition is what I call “glitch purism” — a glitch holding fast to its origin story.

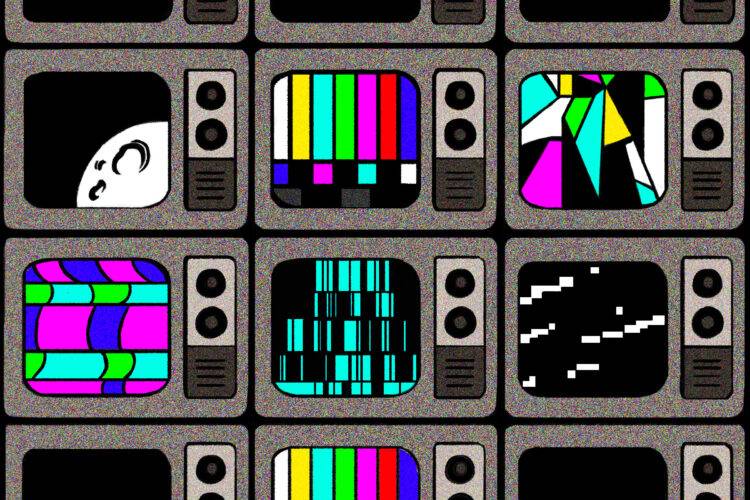

As electronics proliferated in the ’60s and ’70s, many more glitches were seen and heard as the result of invisible flaws in the circuitry. First thought to be bad things, in time, people learned to relax through these temporary states of flux, and some appreciated them for their own aesthetics that were unrepeatable, at least on demand. “Snow” on television screens became a sort of ambient lighting, static white noise with its own sleep-inducing visuals. Car alarms triggered by loud noises, stray cats, and staggering drunks became atmospheric soundtracks.

In this context, glitches without frequencies would seem impossible. This was “pre-code time,” that is, post-Lovelace and C programming, but pre-Python and Java, i.e., when coders worked mostly at computer companies. In industry and the arts, mass production and reproduction embraced their potential to make identical copies: a series of photographs, lithographs, and engraved prints considered irregularities as undesirable as if they were to be detected in a can of Coca-Cola or a loaf of Wonder Bread.

By the 1980s, more than half of Americans had cable television, meaning — you guessed it — the problem of radio wave malfunctions was sharply marginalised. But a whole new variety of glitches took up a lot of slack: code errors.

Synthetic instruments and sound machines ascended, and manipulations came into vogue, popularising the layered sound of the ’60s with MTV era groups of the ‘80s like Duran Duran (the name itself nearly a glitch), recording twitching, repeating frames of words and movements (such as in their song “The Reflex”). This trend yielded to sampling, overdubbing, and mixing of occasional sounds. Some of it was accidental, but much of it was deliberately meant to accentuate, even luxuriate in, what could be heard as a luscious error.

Sound distortion has much earlier origins, as does the distending and distortion of materials in art making. These can be mortared ‘into the glitch’ so the distinction between accident and its amplification is now occasionally (perhaps usually) blurred.

And so to the 2020s, where sameness and uniformity are no longer celebrated as they once were, tiny nuances are the distinguishing watermarks of our individual identities.

The School of the Art Institute of Chicago has given birth to a few glitch artists, some of whom even identify as such. Emerging from the Department of Art and Technology / Sound Practices (AT/SP) is a self-organising group called //sense (affiliated with but not sponsored by the school) who organized the performances, “knock, and the doors of perception will be opened to you” and “Sound Waves” at the International Museum of Surgical Science on Lakeshore Drive and a community center on Elston Avenue in 2024.

Tom Sibley (Bachelor of Arts Art and Technology 1996) — himself a glitch artist of sorts — described the events as “jarring yet pleasant, sensory overloads that reaffirmed his faith in the next generation of electronic artists and audio/visual deviants.”

Ranging from bio art and bird automatons to “dirty audio visual mixing” as performer Omnia Sol (MFA 2025) described it, the events were “an intermix of media, technology, and performances.”

Gordon Fung (MFA 2024), the events’ curator, created an interactive feedback loop between disintegrating and reassembling video color bars, static, and crunching decibels. Fung describes his work as “using feedback loops to create generative materials” and “employing organized chaos to deweaponize the tools of propaganda and regain agency through the repurposing of technologies.”

“[Fung] had me at the opening seizure and sound level warning,” said Sibley.

Sibley is also a hybrid artist at Labforms (@labforms) who studied kinetics and electronics, holography, video processing, sound, and film theory. Working in image visualization for over three decades, he’s invented and patented a number of spatial projection systems ranging from video holograms to auto-stereoscopic and panoramic projectors. His work explores “glitching” eye brain physiology into perceiving volume and depth of field without the need of 3-D glasses or headsets. He is currently working with architects and designers to convert drawings and models into video holograms and glasses-free mixed reality. His most recent installation, “Alien Antennae,” produced at Aktuelle Architektur Der Kultur (AADK) in Blanca, Spain, used AI, 3-D visualizations, sound sculptures, and video collages to imagine an alien perspective of human civilization.

AADK (@aadkspain on Instagram) should be considered by SAIC students looking for international experimental residencies. They have announced an open call for one month residencies on the theme of space and memory with a deadline of Nov. 20.

Glitch art exists far beyond our Chicago art school bubble. Glitching is a global art-making tool. For example, U.K. artist Amiangelika (@amiangelika) uses frequencies and glitches in performance. With her sound partner and electronic music producer, 1100 (@11hundred), Amiangelika fuses digital and analog sound with moving images to create feedback loops. Their installation “BLCK SUN” at the Outernet London spread across the ceiling and walls in an outdoor overhang adjacent to a theatre. It was the kind of immersive work that lives up to the name. The show has travelled across the world— from Times Square to Buenos Aires.

Jake Elwes is another artist last seen (by me) at the Victoria & Albert Museum with governing objectives too gloriously complicated to explain in this short treatise. They might even object to a “glitch” classification. The Zizi Project (2019-ongoing) hypothesized that AI would struggle to recognise trans, queer and marginalised identities, and by failing to do so contribute to the inertia of heterosexual norms embedded in society. They noticed that certain frames frequently glitched when they couldn’t understand a performer’s movements By creating a digital drag show deliberately hybridising identities, they wished to adjust this bias. Their body of work continues to develop (@jakeelwes). Those interested in modern curation of digital artists in London should follow Gazelli Art House to view their current roster of residents and new artists.

Glitches can be over-conceptualized. They are not “skin.” They are not “cyborgs.” They are not even necessarily “voids,” though I am partial to the definition given by Rosa Menkman as “breaks in the flow of expected information.” Glitches can as easily be surpluses as deficits, and they may or may not provide ground for what a social anthropologist calls re-levelling.

But glitches can be fascinating, and even useful. In physics, “glitch materials” are being developed to create environments for testing quantum particle interactions, magnetic fields in rock samples, and thermodynamics in living cells.

Glitches are not political per se, though they have been deployed for various political and social causes: a methodology for embracing failure, discarding the hegemony of canon or patriarchy. In her book “Glitch Feminism,” Legacy Russell champions glitch as emancipation from “the trap of visibility in lieu of fair and equal representation under systems of supremacy.” “Failure,” she argues, “is not the opposite of ‘visibility’ or ‘power.’”

“Bodies that ‘fail’ are bodies doing radical work, refusing to center and aspire toward legibility within a society that demands assimilation into an ableist, racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic framework in order to be deemed deserving of life.”

The Brooklyn Rail leans into her perspective. In reading the coverage, perhaps more people “in the margins” will become aware of new interpretations that allow them to acknowledge and tap into these sources of power.

“The machine world is machined by us out of the world, and we have machined the world. It’s our world, in the sense we have crafted it. And we’re constantly crafting and re-crafting it. Then it produces errors, mistakes,” said glitch artist Jon Coates in a 2014 interview with Hyperallergic.

While it can serve many purposes, glitch is not malware nor intentional data corruption. It is not alchemical, a filter drawn for encryption or conversion of one type of material into another. Glitch is not subversive, per se, just as it isn’t any type of art per se, even if that art challenges everything that came before it. It may have taken fifty years for punk rock to be played at a Coronation Ceremony, but the anti-establishment does often get folded into the establishment, and that occasion neither creates nor destroys that which is glitch.

Please follow @revedinlibert for connectivity across national boundaries in art and technology. In October and November 2025 she is curating an installation that imagines how modernist art might be reconstructed by AI for the 21st century. LightForms – Future cities of the Past is at Roca London Gallery from 16 Oct. through 25 Nov. 2025 https://www.rocalondongallery.com/storefronts/lightforms-future-cities-of-the-past