“Conversations at the Edge” is a seasonal series consisting of screenings, performances, and talks given by contemporary media artists both up and coming and at the top of their game, and answering the question “what’s happening globally in the world of media?” Coordinated by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s department of Film, Video, New Media, and Animation, and in association with the Gene Siskel Film Center, the 2024 season for “Conversations at the Edge,” continues to generate more stimulating, and invigorating dialogue for screenwriters, directors, animators, and artists alike amongst our campus. Hosted at the Gene Siskel Film Center, tickets are $13 for the general public, $5 for SAIC faculty and staff, and free for SAIC students.

“Conversations at the Edge” has a history of bringing in fantastic artists internationally to share their work and engage with our student body, with filmmakers such as Lawrence Andrews, Lizzie Borden, and Tsai Ming-Liang in attendance at previous series, spreading their vast knowledge and experience with the community here at SAIC. This year’s lineup is no different, starting with Polish animator Tomek Popakul.

Graduating from Łódź Film School, Popakul is an animator, graphic designer, musician, and music video director. Popakul is currently recognized as one of the top animators in the world; viewers and experts alike are constantly awed by his style and approach to the medium, as well as his ability to use storytelling to generate immersive worlds with cutting edge animation. His last two films swept at various film festivals, with screenings at the Ottawa International Film Festival and the Sundance Film Festival. One of his films “Acid Rain” (2019), received a prestigious Annie Award nomination, and two of his films, “Acid Rain” and “Zima” (2023), were longlisted for the Academy Awards. Tomek continues to make films that provoke, stun, do not demand closure, and above all, speak for themselves.

At the Gene Siskel Film Center, three of Tomek’s shorts were screened and accompanied by a Q&A session. The first film, “Ziegenort” (2013), was a Poesque tale of a boy growing up half human, half fish. The film used audio to create tension, making some sequences equally disorentating and engaging. With a charming animation style and immersive cinematography, the audience becomes a part of the landscape of the film.

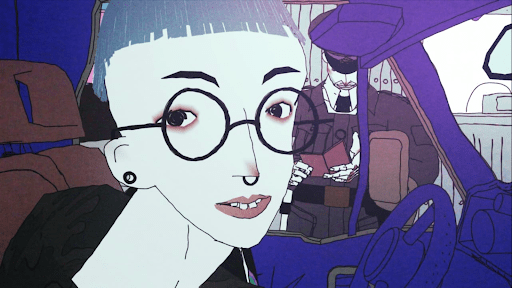

The second film screened was “Acid Rain,” which is like if the film “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” was an Aphex twin song. “Acid Rain” follows a teenage runaway who hitches a ride with a stranger to embark on a journey with no particular destination. A love letter to rave culture, the film seamlessly meshes 2D and 3D animation. This is combined with a masterful use of POV shots that make you feel as stressed and high as the characters on screen. And a film about raving would not be complete without electronic and trance music with and beautiful trippy visuals. Not to sound like a cinema purist, but “Acid Rain” is a movie best watched in a theater on the big screen in order to fully be able to soak it all in.

The third movie screened that night, “Zima,” takes place in a small fishing village, on a freezing winter night, where the relationship between humans and animals becomes reversed. Equipped with beautiful visuals, provocative iconography, and a heavy metal soundtrack, “Zima” truly emphasizes how some things really can only be done in animation.

Popakul attended SAIC on Sept. 19 accompanied by a screening of his three films.F Newsmagazine spoke with him afterwards.

Kate Mauthe: Do you have any particular artists and filmmakers that inspire or have influenced you?

Tomek Popakul: I would say [that my influences] are divided into more far ones and more close ones, because sometimes you say, “I’m inspired by this and that,” but it’s nothing similar to what you are doing, so it’s very hard to see the connection.

I think the things that are close to my style visually would be René Laloux’s film “Gandahar” (1987). I remember very vividly these images, and for me, it’s proof when an image is very strong, it stays with you for your whole life. I forgot all the movie, but I remember some blurry images. When I became an adult I found this movie again, and it was still great. I would pinpoint this as one of my influences [as well as other] animations from the ’80s and ’90s, I was watching them mostly on VHS, so specific quality of the image had a very big influence on me.

I live now in times when everything is 4K ultra HD, and so on and it’s super sharp. I actually by logic think you should follow the spirit of your times and be more contemporary, but I can’t help but follow these nostalgic images. I would say my films have a normal live action movies structure: their characters’ dialogues and plots so they could be basically shot by camera, so my inspirations are also from live action movies. For example, one movie about small communities I really like is a very old movie called “The Last Picture Show” (1971). I like the stories about something that happens in some community with a limited amount of people.

I was [also] inspired much by something that I [watched] with my mother on Polish TV. It was called “Theater of Television.” They were much less spectacularly shot than the movies but they were a tiny bit richer than theater. I was amazed how very layered stories you can achieve [when] you have just some characters in some space and there is some interaction between them.

KM: You talked about how your experiences growing up in your village gave you lots of inspiration for your film, “Zima,” but beyond that, how has your upbringing influenced your art and the stories you decide to tell?

TP: I think people are affected much by environment. Nobody chooses where you have been born. I mean once you’re [an] adult you can choose. But I feel a strong connection with [and] I have luck to be born in a village with access to nice water, a lagoon, and we have a very big deep forest that you can walk in for hours and not see a human. I’m always saying that [the] forest is my church, [the] forest is my temple. I live very close with nature. And also my father is a fisherman so he has a job [where] you get the food directly from the environment. His work schedule refers to weather and season: He gets up early in the morning, and he checks if it’s windy today or not, he starts fishing in the spring and he has free time during winter. Our family [was] living according to the cycles of nature, and, for example, there was one year [where] there were many fishes and sometimes there were no fishes and nobody knew why, so even how you maintain yourself was influenced by nature.

I can talk a lot about my village. I’m not very patriotic about Poland, but I’m just a local patriot of my village. …Small community … It’s nice and cozy, intimate, but the bad part about a small village is that everyone knows everything about everybody, so to keep your space, you know, everyone has some of their own secrets and so on, so it’s a very dense situation.

KM: Music plays a massive part in the overall composition of your films, and I know that you are a musician yourself. What role does music play in your life in terms of your art and beyond your art?

TP: I could live without watching movies, but music is this big part of my life. Music is very stimulating for me, and my imagination, and when I hear music I see scenes or landscapes or characters.

As a kid I was drawing illustrations to some music I liked. I remember my father had two albums, one was King Crimson, prog rock, and Duran Duran, ’80s pop, and that was my first moment when I started to imagine movies. Later I had a cousin who had the biggest collection of cassettes in the village. He was the first music nerd I saw, and he was much into rap from the ’90s, so he showed me Wu-Tang Clan and Snoop Dogg. Later, in my village, there was a lot of listening to Techno, or something that was named as Techno, but it was more like a very cheesy Trance. My village is very close to Berlin, so all this music from this massive event called Love Parade was coming.

But then I moved to art school, to the city, and there I saw for the first time [saw] people from subcultures, and people listening to more metal, more guitar music. So my art school was filled with goth, punk, and metal people. When it comes to youth culture, what music you like plays a big role in forming your identity. Music is a great social glue. When I became an adult and I started to play music and go to concerts, I made many friendships through music. For me, the music itself is 50 percent of the experience, but another 50 percent is being with people. We have a community radio in Warsaw called Radio Kapital, where actually anybody from the street can apply and say, “I want to have a radio program,” and you get assigned a slot, and once a week you prepare a one-hour long mix with whatever you want. So it’s very awesome. I met many people by just [saying], “oh, can we make this program together, half of the tracks will be mine, half yours.”

I feel inspired not only by the sound of music, but also the names of the bands, or titles, or lyrics in particular. One of many artistic influences is such a guy from the Polish punk rock band called 19 Wiosen. In Polish, it’s Dziewiętnaście Wiosen. It’s very hard to pronounce, but the translation of this name is 19 Aprils (19 Wiosen), which means in Polish that you are 19 years old, and they started this band when they were 19 years old. Marcin Pryt, the frontman and the lyricist, he’s now 50 something.They played for decades. It’s a very niche band, but his lyrics are very special. He’s from Łódź and he writes about his city in a very magical way. I read his poems in high school, and those words stayed in my head, and finally I moved to Łódź to study in film school. My friend said “this guy works in a library,” and you can just go and meet him, and this is how we became friends. I would want to make a movie based on his lyrics, and so far I have made a music video for them. Also in “Zima,” in the church scene, the organ music is actually one of their tracks. I joke that I want to be buried in this band’s T-shirt. It’s such a small band but [has a] hardcore group of fans, and people can sing their lyrics from memory.

KM: When did you realize that you wanted to be a filmmaker?

TP: As a kid, I was reading a lot of comics. When you read comics and you know how to draw, sooner or later you will want to draw your own comic. It’s like a storyboard, making [a narrative] of the pictures there. And I went to art school, and I was interested much in 3D graphics without any intention of being a filmmaker, with no big ambitions or plans. I was feeling very so-so during highschool. So the reason I tried actually [was] to not go crazy. Instead of thinking about how bad I feel, I should put this energy into something that takes time and it’s kind of never-ending, which is working on animation. So, I get up in the morning, and I don’t think about my life, but I think about the next shot. Working on animation helped me to go through hard times, just to focus on one thing to do, and over the years it led me to places and people that I would not have expected.

KM: Your films have so much diversity in terms of themes and subject matter, how do you hope your art and filmmaking impact people?

TP: I don’t know. I would say my works are very subjective and personal. And when I’m thinking about the role of artists in society, I’m not sure if I believe that art can change the world in such a direct way. Like, I don’t know, you make a movie about … “stop war” or something, it will not make the war stop, but the main idea is that you describe something that many of us, maybe, feel inside. If you are too shy, or you don’t know how to put it in words, or you never think about it, and you’re watching it, then you feel that you are not alone. You can watch a movie, and you can feel, “Oh, actually I was feeling exactly the same.” So it’s sharing what’s deep inside of you. I like to do personal movies, and I also like to watch personal movies, because I think we can communicate as people on some deeper, unspoken level. […] You have this tool to turn difficult experiences into something valuable, aesthetic, interesting. I think it’s good. I think sad movies have meaning.

KM: What part of filmmaking and animation excites you the most?

TP: I think script writing, coming up with ideas is the main creative part. When you write and think about the story and you imagine it, it’s moving your head, and later it’s … I wouldn’t say that it’s just the process of executing it. What you have in your head, but just making it happen. Pushing yourself every day. It’s what I like.

KM: Do you think you could walk through your creative process?

TP: When I have two or three such strong images, I can have a movie. So, for “Ziegenort” (2013), I imagined a boy who is [a fish], he has scales. and he tries to scrape them with a knife like my father does with a fish. Or I imagined there is somebody who takes a knife and cuts [the side of his neck],and then there are fish [gills]. And that moment, in the final movie is, like, two seconds — it’s almost not noticeable, but meaningful. I have those moments and then I build a story to connect those images together.

If filmmaking in any sense of the word is something that interests you, consider checking out the remaining sessions of “Conversations at the Edge,”SAIC’s critically acclaimed series, with dates on Oct 17, Oct 24, Oct 30, and Oct 31.