Media reactions toward Koons’ broken piece. Internet source.

Jeff Koons’ signature icon “Balloon Dog” got accidentally destroyed by a visitor at Art Wynwood, a contemporary art fair, in Miami on Feb 16, 2023. What rings are not the shattered clamor, but the outburst of coverage on the discussions that followed. Flooding social media and arts news, Koons’ “misfortune” turns out to be a chance for the art market to resurrect this broken kitsch work into a golden opportunity of reselling it at a higher price. This series of overpriced “Balloon Dog” has sparked controversies due to its kitschiness. “Balloon Dog” is a series of Limoges porcelain sculptures crafted in Bernardaud Porcelain — a French family business founded in 1863 in Limoges. The limited edition of 799 shines in various sizes and hues: blue, magenta, yellow, orange, and red. The most expensive one, an orange rendition, sold at Christie’s, an auction house, for $58.4 million. The particular “unique” one broken at Art Wynwood cost $42,000 before it was smashed — fulfilling an Adornoian prophecy on how the cultural industry exists at its worst.

The shocking part of this “Balloon Dog” breaking may not be the incident itself, but the aftermath that collectors might want to make an offer to purchase this “blown up balloon.” Along with all the sudden attention granted to Koons, one wonders if the “offers” are simply performative or if the “accident” could be a staged one — as Stephen Gamson, an art collector on the spot, once thought.

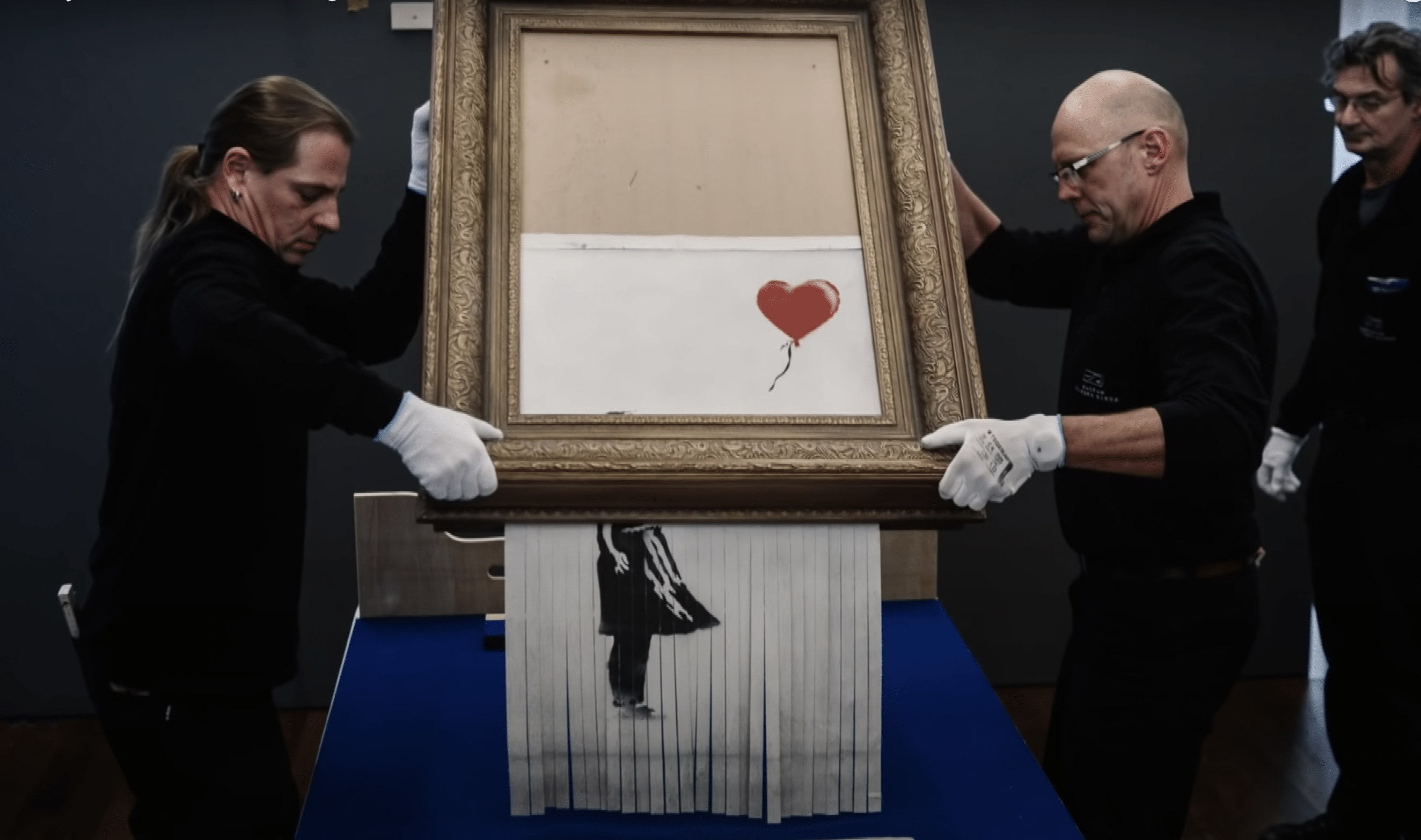

This high-profile incident harkens back to Banksy’s dramatic “Girl With Balloon” auction in 2018 at Sotheby’s, where Banksy’s absurdist device shredded the painting in front of uninformed bidders after it was sold. Banksy’s “torn” work, soon renamed “Love is in the Bin,” went from an offered price of £1,042,000 to a resold price of £18,582,000. This more-than-tenfold increase invites us to rethink how the art market dictates. But as a reminder, Koons’ broken dog was listed at a mere $42,000 prior to breaking.

Banksy’s “Love is in the Bin.” Screengrab via Inside Edition.

Beefing up his “Balloon Dog” series, in 2013, Koons claimed “I’ve always enjoyed balloon animals because they’re like us. We’re balloons. You take a breath and you inhale, it’s an optimism. You exhale, and it’s kind of a symbol of death.” Unlike a real balloon dog that brings joy to children, Koons’ optimism comes with a cost — typically five-digit. Such a delight presents nothing more but a broken promise. After all, this contentless balloon, with its disingenuous shell, contains nothing more than an egoistic breath — as Clement Greenberg asserts, “Kitsch is deceptive.”

Koons, in his 2015 lecture “Jeff Koons Returns to SAIC,” commented on his use of reflective surfaces: “The idea of a reflective surface affirms you…you see your own reflection. It is informing you that the art happens inside you. It is an object, just a transponder. Nothing happens in it. There is no value in art.” Clearly, through reflection, he tells the truth that some “objects” can be intrinsically valueless — this echoes Michael Fried’s discussion on how arts simply fall into a mere object through “objecthood.” When an artwork becomes merely an object, it poses a dilemma to viewers of what arts can be. The kitschiness of the “Balloon Dog,” as an “object,” sparked controversy at the Château de Versailles as it appeared crude and too modern for Louis XIV’s former palace — clearly “pets are not welcomed” in this castle, neither is an overly mundane “object.”

When it comes to references to daily objects in arts, artists can still infuse artistic value through subtlety. For instance, Marcel Duchamp’s readymade “Fountain” (1917), also controversial, is more valued as it challenges the art scene and audiences. Both the “Balloon Dog” and “Fountain” represent “objects” and have multiple iterations. But my admiration for Duchamp credits to his criticism of the corrupted art scene. Duchamp’s “objects” stand the test of time as conceptualism speaks for itself. Most importantly, Duchamp pokes fun at the hypocrisy in the art market. The “Balloons” are, however, merely pokable objects that burst into their egoistic fallacy. Duchamp’s broken glass — “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even” (1915–23) — certainly makes a case (well, it literally does), for it justifies its cause to embrace absurdity genuinely; Koons’ broken porcelain, by no means, invited the media and market to make a scene.

The art market, like a black box, often controls what is accessible to the mass public. Such obfuscation hinders the showing of arts that present critical commentaries in response to political, social-economical, gender issues, and beyond. This is especially true in the realm of Pop Art, where the market largely dictates the scene. Crowned as one of the “Fathers of Pop Art,” Andy Warhol’s screen prints of Campbell, Elvis Parsley, Marilyn Monroe, and Chairman Mao predominate the narrative of his endeavor in the public eye. His experimental works, however, remain largely disregarded. Warhol, a prolific filmmaker, produced over six hundred films that even most “admirers” are unaware of. To name a few of his outrageous productions, “Blow Job” (1964), a 35-minute film showing DeVeren Bookwalter receiving fellatio from a group of, potentially, “five beautiful boys;” “Empire” (1965), an over eight hours slow motion footage of the Empire Building; and “Eating Too Fast” (1966), another fellatio-related 67-minute film. With collectors and the general audience’s over-fixation on Warhol’s more approachable posterized print works, his films are only known and accessible to true enthusiasts.

Still of Andy Warhol’s “Blowjob.” Screen capture by Gordon Fung

The art market’s taste declines, but Koons’ recognition is certainly boosted. As much as collectors crave to lick the spilled milk from the shattered balloon, I personally love Warhol’s “Blow Job” more — this daring work remains one of my favorites of all time. My major concern is that kitsch will continue to make its way to further the art market’s dominance through the cultural industry, consumerism, and capitalism. “Pop Art masters” and “kitsch makers” will continue to confound the art market with their eye-candies, but the avant-garde camp will surely safeguard and carry on the Greenbergian mission, where avant-garde serves “to find a path along which it would be possible to keep culture moving in the midst of ideological confusion and violence.” So, bring it on.

Gordon Fung (MFA FVNMA 2024) is a transdisciplinary artist working with experimental video art, multi-/ new media, installation, sound art, audiovisual performance, and conceptual arts; also a runaway composer, writer-in-closet, and metalhead.