On Nov. 24, the Chicago City Council approved Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s budget proposal for 2021. This year marked the second year in a row of an “unprecedented level of community engagement,” as noted in the budget overview, which involved a survey distributed to residents and five virtual town hall meetings broadcast on Twitter and Facebook. Unlike last year, there has been an overwhelming and widespread call for the city to reexamine the police budget — both through these official routes and through continued protests against police violence.

In June an op-ed was released by the Chicago Sun-Times, co-authored by six aldermen across the city, all members of the City Council’s Socialist caucus. The op-ed was a call to cut police funding for the sake of public safety, pointing out that the city spends nearly $5 million on policing daily. This is what mental health services get in five months, what substance abuse treatment programs get in 18 months, and what violence prevention programs get in two years and eight months. They wrote, “Chicago needs enormous public investment to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, and when we sit down to hash out a budget this year, we will be faced with a choice: we can cut policing, or we can slash basically everything else.”

Chicago is facing a roughly $1.2 billion budget deficit, 65 percent of which is due to the current pandemic. Mayor Lightfoot is cutting the police budget by $58.9 million, or about three percent of their current budget. The majority of this reduction comes from cutting now-vacant positions. She has stated that she rejects “the false narrative that it is either fund the police or fund communities. We must and can do both.” City funding for community services rose by $10.6 million in the proposed budget, particularly funding for Chicago Public Libraries, Chicago Department of Public Health, and the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities; however, funding for the Department of Family and Support Services was cut by $22.7 million or about three percent of its current budget.

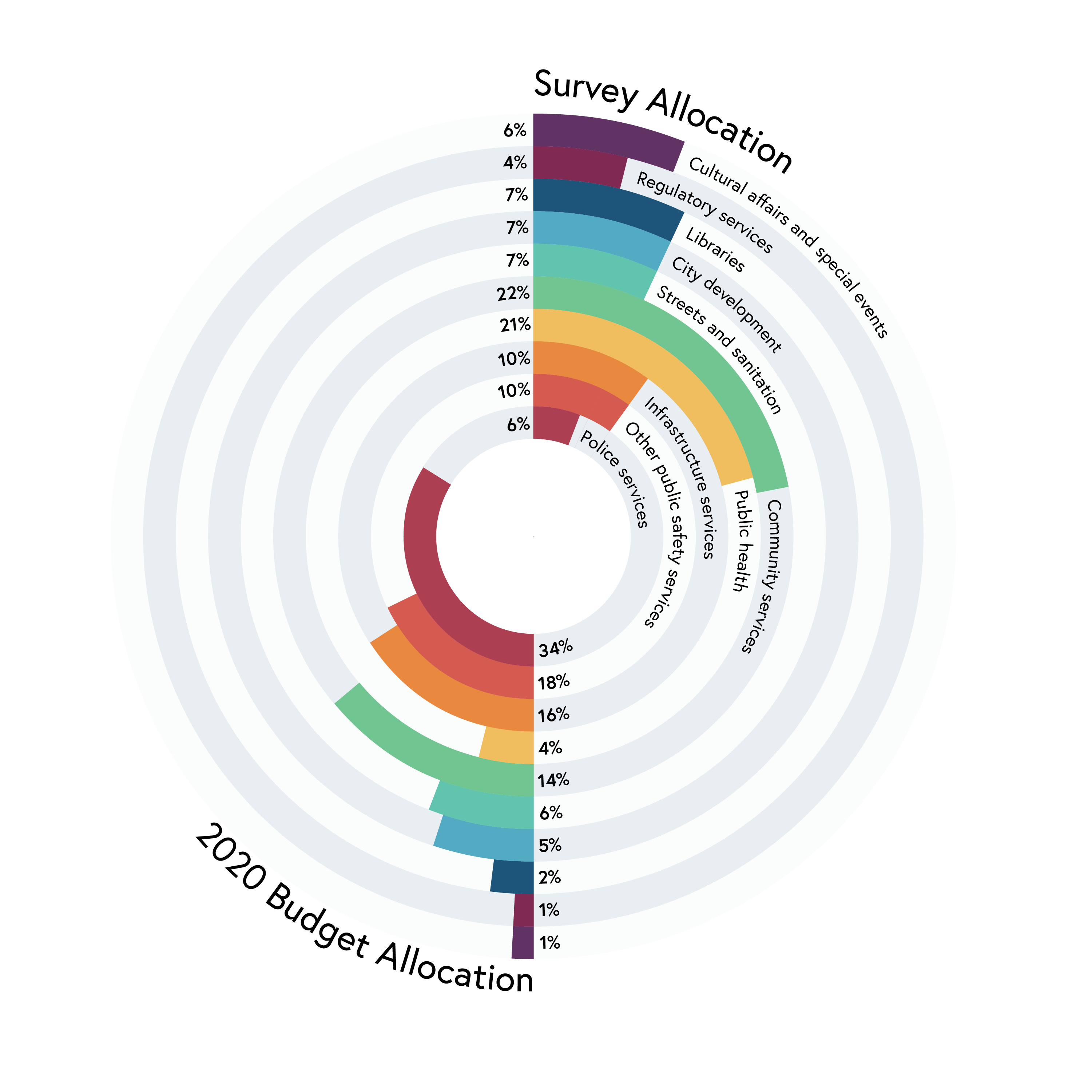

For a single optional question asking respondents to share “other concerns or revenue ideas related to the 2021 City budget” the city received 8,168 comments about defunding the police, out of 19,650 comments total, only 1,042 of which didn’t mention the police. The city asked respondents to distribute the city’s budget between police, other public safety, infrastructure, public health, community services, streets and sanitation, city development, regulatory services, and cultural affairs and special events.

The responses to the survey were used to inform focus groups, which were distributed more equitably throughout the city than survey responses, and town halls on the budget. Comments made in the focus groups also reveal the concern throughout Chicago about the state of policing and its budget; one focus group member said, “We need to invest in the root causes of crime. Community violence intervention programs have proven effective, and I am tired of wasting my taxpayer money for having incompetent police officers settling lawsuits with families who have to deal with harm from police.”

Another respondent highlighted the need for mental health resources on the South Side, citing time, labor, space, and living wages as necessary components for improving mental health services in a community that needs them: “The budget framing does not need to be an equal distribution, but it needs to be equitable.” Restorative justice, alternatives to police, and reparations for those imprisoned because of the criminalization of cannabis were all mentioned as important aspects of investing in under-served communities.

One person said, “For too many people in the city, calling police heightens violence and even death … We need to put funding toward creating alternatives, concrete, sustainable, sensible alternatives powered by people and well-managed, with clear systems and operations as well as transparency. [I believe the] city of Chicago has the capacity to do this!”

The city of Chicago has not done this. As Ald. Rossana Rodriguez Sanchez (33) has put it, “[Lightfoot] looked for feedback. She received the feedback. She did not like the feedback.”

New budget, old patterns

The CPD has consistently received around 40 percent of the city’s budget for decades despite violent crime steadily declining for the last 30 years, and the rate of police solving murders dropping. Mayor Lightfoot has been involved in Chicago city government police oversight on and off since 2002, at times pushing for stricter responses to officer violence than CPD but also drawing criticism from activists for lack of thoroughness and accountability.

In 2018, the city spent $97,801,760 on settlements related to police violence. They set aside $152 million for the same purpose in 2020, separate from CPD’s $1,778,002,408 budget. As the call to defund the police has become more visible, Mayor Lightfoot has pointed to the fact that the majority of the police budget goes to personnel, specifically stating that “diverting money from police would mean the youngest, newest officers — who are also the most diverse and well-trained — would have to be let go.” According to city data, the lowest salary of any Chicago police officer is $48,078 a year; the highest is $96,060. Before Governor Pritzker signed off on a new $40,000 minimum annual salary for Illinois teachers, the minimum teacher salary ranged from $9,000 to $11,000. Teachers need twice the time in training than police officers do in order to become certified.

The pandemic factor

The primary economic concern right now is dealing with the COVID pandemic. To that end, it’s worth pointing out that as of early October, 950 people in the police department have tested positive for COVID since the pandemic began, about eight percent of the department. There have been ongoing reports and photographs of police officers not wearing masks on duty, most glaringly at protests against police brutality; everybody regardless of occupation has been required to wear face coverings in public since May 1, and last month Mayor Lightfoot called for “updated strategies” in every city department to ensure employees are wearing masks.

Understanding the public response

This year’s budget survey got 38,336 responses total — up from 7,347 in 2019. This year, 3,855 of responses were from just outside city limits on the South and West sides. According to the 2010 US census there are 2,695,598 people in Chicago, about 2,638,000 of whom are adults; this means only about one percent of the city responded. Forty-five percent of these responses came from the North Side, which represents 24.6 percent of Chicago’s population. Responses from the South, South West, and West sides totaled only 21 percent despite those areas housing 51.3 percent of Chicago’s population.

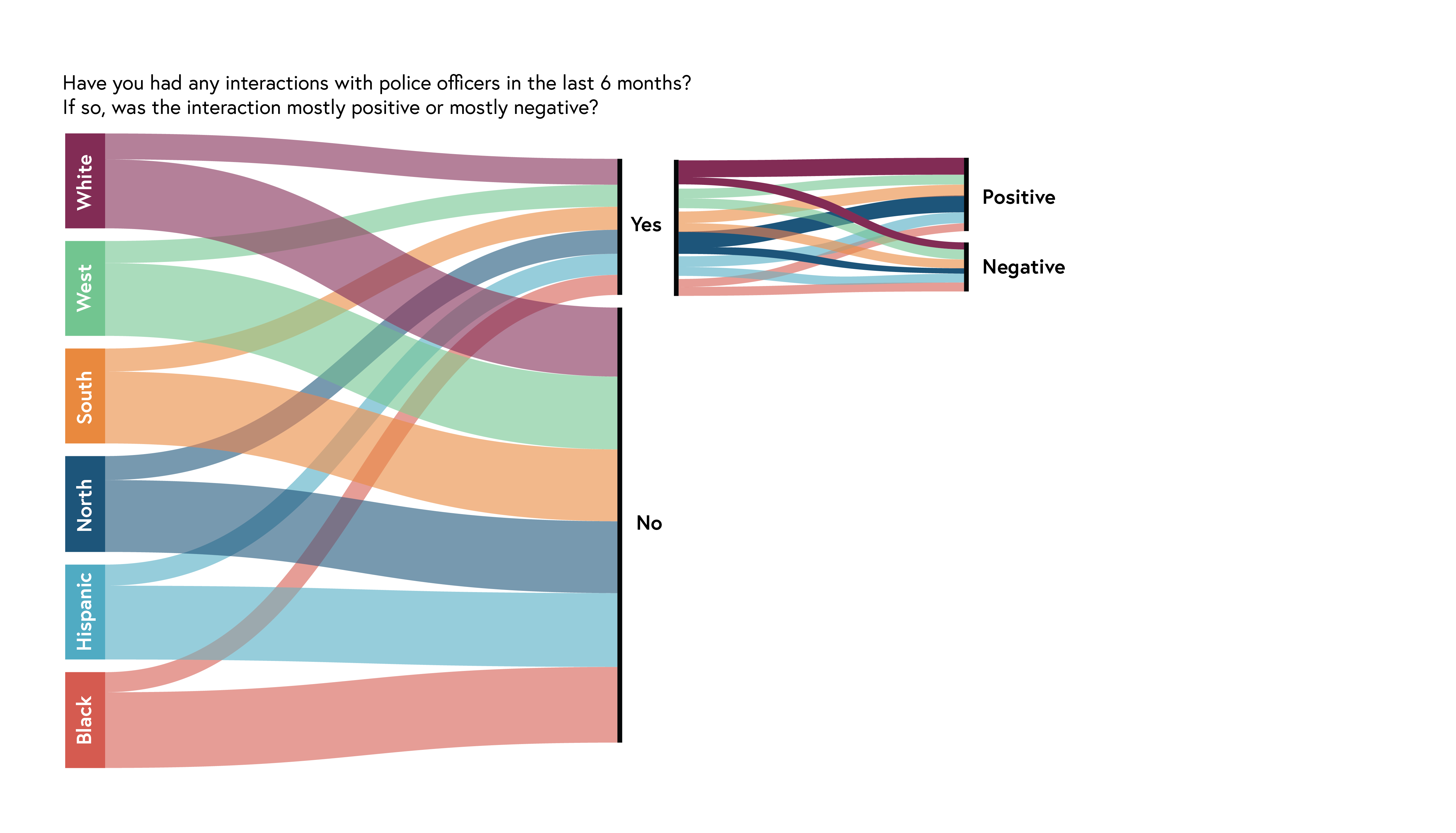

At face value, this might appear to be a major geographic bias, but it’s worth looking at how exactly attitudes surrounding the police among North Siders may have shifted in recent years. A survey conducted by The New York Times and the Kaiser Family Foundation in 2016 found that, when compared to Chicago as a whole, people living on the North side were more likely to say CPD were doing an “excellent” or “good” job.

As a group, respondents on the North Side were whiter and richer than the rest of the city. People on the North Side were also just as likely as the rest of the city to have had an interaction with the police in the previous 6 months, but those interactions were almost half as likely to have been “mostly negative”.

The city’s budget survey in 2019 informed this year’s budget. Like this year’s survey, it was meant to give the city “guiding principles” and “an opportunity to communicate the difficult choices to be made through the budget process.” Responses were also predominantly from the North side. Almost half of respondents indicated that information related to City spending on police was of most interest., and about one percent of respondents mentioned the Chicago Torture Justice Center. More than 39 percent of respondents said they would decrease the police budget to balance the city budget overall. Despite this, respondents only set the police budget 4 percent lower than the city did in the 2019 budget, and put less money into community services (which in this survey included public health) than the city did at only 13 percent of the total budget versus the city’s 18 percent.

The geographic skew to the North Side points to the city doing, at best, an inadequate job distributing the survey. I would argue the shift in responses is because the distribution is falling to individuals who pay attention to local politics; these people would probably be more likely to be politically engaged generally and be familiar with the argument to defund the police, and so would the people finding out about the survey from them.

F Exclusive: A Survey About the Survey

I surveyed some Chicago residents about their experience with the city’s budget survey. The sample size was ten, with a large chunk of respondents being current SAIC undergrad students. Of the ten people I surveyed, two took the budget survey this year and none took it last year. The two who did take the survey both said they did so after seeing people they know or accounts they follow promoting the survey, although this wasn’t the only reason they took it (one respondent specifically said they took it because “The city needs to hear that people want to defund the police.”)

One person who did take the budget survey highlighted something very important: The city “Committed a grave numeracy error by mixing units — they said that the city spends 1.7 billion dollars on police and expressed every other spending category in millions.” To put this into context, 1 million seconds is about 11.6 days; 1 billion seconds is about 31.7 years.

Another respondent said they were “pretty outraged to now know that I received absolutely no information on the budget survey, or else I would have absolutely participated, and I would be more educated on these issues.” Everyone who responded felt the city’s top budget priority was the police, with one person specifically mentioning “appeasing the FOP” and another adding “maintaining good relations with wealthy neighborhoods and high tourist areas that bring in the most money.”

The main reason people gave for not taking the budget survey was not knowing about it; only one person who didn’t take it reported seeing any advertisement either year. Only three people saw any kind of advertisement, and only one saw an ad outside the Internet (on CTA property in the outer loop).

Lightfoot responds

The budget survey was framed as a new turn towards real input from Chicago residents in the budget process. The survey was by no means a perfect representation of Chicago residents, but it demonstrated a major concern that has been disregarded. Mayor Lightfoot personally tweeted telling people to take the 2019 budget survey 9 times during the roughly 2 month window it was available. In the same window in 2020, she tweeted about opportunities for civic participation a total of 16 times; just 4 of these tweets were about the survey. In one tweet from this year, Mayor Lightfoot wrote: “Even in the face of this fiscal crisis, the challenges we face require us to lean into our values of equity and inclusion — not discard them as luxurious indulgences for easier times.”

This sentiment was echoed in her recent statement regarding the just-approved budget for 2021, released through the Chicago Sun Times under the title “Why I am asking you to support one of the most painful budgets in Chicago’s history.” Mayor Lightfoot addresses concerns about the $94 million rise in property taxes, which she says will cost the average homeowner about $56 starting in 2022. She also addresses why the city is increasing taxes to close the budget gap instead of draining the ‘rainy day fund,’ calling this a ‘rainy season’. Absent is any mention of CPD or their budget. The closest we come is an acknowledgement of the needs of the city’s most vulnerable residents: “We could absolutely abandon these residents and others, as well as the values of equity and inclusion as luxuries for better economic times. The fatal flaw of that strategy is that leaving people high and dry is not cost free. We have and continue to pay a price for our neglect of people, and neighborhoods.”

It’s hard to disagree with this last point. To repeat the words of some of our aldermen, “We can cut policing, or we can slash basically everything else.”