From denouncing Mexican immigrants as criminals and rapists to imploring Congress (and, by extension, taxpayers) to build and pay for a border wall, President Donald Trump characterizes Mexico as a den of thieves, the cesspool in which America’s worst national maladies breed. But “In a Cloud, in a Wall, in a Chair: Six Modernists in Mexico at Midcentury,” on view in the Art Institute of Chicago through January 12, invites us to think otherwise. By bringing together the work of Clara Porset, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Anni Albers, Ruth Asawa, Cynthia Sargent, and Sheila Hicks, the show casts Mexico as an epicenter of modernism, and as an asylum for political and artistic refugees.

Porset’s communist affiliations forced her out of her native Cuba and into Mexico in 1935. A frequent correspondent — and would-be student — of Walter Gropius and the Bauhaus, she developed the urge to design essentially Mexican furniture, pieces which reflected and could be seamlessly absorbed into Mexican culture. This desire eventually materialized in her Butaque Chair, whose low, slow curve looks like it could cradle the sun as easily as a human body. The chair’s shape is familiar; chances are you’ve reclined in one before. For Bauhaus artists, this is a mark of success — an aesthetic design at once economical, nice to look at, and intuitively useful. The Butaque Chair’s familiarity means its design and function are embedded in our furniture vocabulary.

Fearing espionage in the wake of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942. For about two and a half years, more than 100,000 people of Japanese descent — mostly U.S. citizens — were imprisoned in the “relocation centers.” Among them was Japanese-American Ruth Asawa, who, after the end of the war, took a class with Porset in Mexico. She derived inspiration from Tolucan looped-wire baskets, and employed the technique in her slender, symmetrical looped-wire sculptures. Graphite-gray, suspended from the ceiling, the sculptures often consist of two or more concentric bodies; like cross-hatches, their moments of overlap deepen each other. You think about pregnancy — perhaps you think about imprisonment. The sculptures are among the most aesthetically compelling pieces in the show — “That’s really cool!” exclaimed one young patron.

The show fails to mention that Mexico, following suit, instituted a similar anti-Japanese policy during WWII. It affected many fewer people, and occurred only after FDR got the ball rolling — but still, it would be irresponsible to think of Mexico as guiltless on this charge.

The most aesthetically compelling pieces in the show are Lola Álvarez Bravo’s photomontages. Perhaps sensing this, curators set “Untitled Mural for Fábricas Auto-Mex” (1954), a huge (around 15’x8’) print at the show’s entrance. The industrial tableau’s centerpiece is a man’s naked torso extending from an assembly line — a 20th century centaur, the writhing mascot of an age whose center will not hold. The photomontages, peppered throughout the show like aesthetic pit stops (especially at the end, when the show’s dynamism has waned), both amuse and unsettle. There’s something childlike about a photomontage. It’s something you probably did in kindergarten arts and crafts; you were tickled to glue a big head of broccoli on top of Derek Jeter. But the industrial chaos in Bravo’s pieces reads more like apocalypse, particularly in view of our world’s dire environmental conditions.

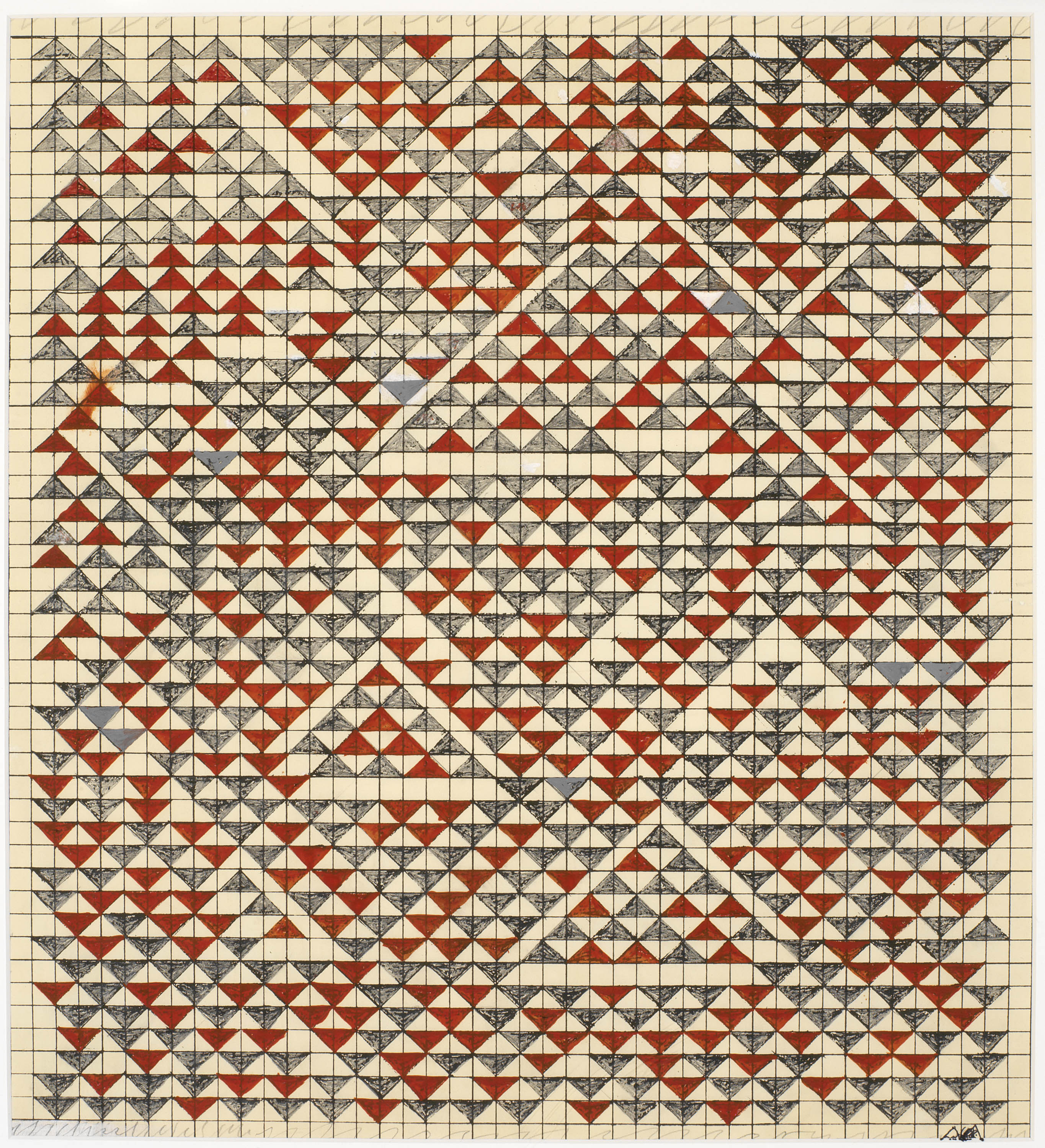

Textile artist Cynthia Sargent moved to Mexico to escape the “dull, somber hues of New York” (per the wall text) in 1951. Accordingly, her rugs are fiery — but playful, using line to mirror the inexactness of nature, not to resist it. This, in contrast to Anni Albers, the German-born leader of the Bauhaus’s weaving workshop, whose geometric tapestries make your brain create and discard shapes and patterns, in search of a mathematical skeleton key. It’s a canny juxtaposition: two poles of the aesthetic spectrum, informed by the same setting.

Least aesthetically compelling is Sheila Hicks’s section, which comes last. The fault is partly curatorial — three rectangles on one wall, one on the floor, one on another wall; it feels haphazard, tacked-on. Given full benefit of doubt, the works are more high-concept. “Learning to Weave” (1960) is meant to look like the product of a novice weaver, not fully in command of their craft. Given less, the straightforward presentation and formal sameness is only dull.

The show’s cousin, “Weaving Beyond the Bauhaus,” is in the basement, a characteristically labyrinthine walk away. The obvious connection is Anni Albers, whose sardonic quotes (“… it is no easy task to throw useless conventions overboard”) flatter the exhibit’s walls. The “Weaving” show reminds us that the Bauhaus encouraged experimentation, which is most apparent in its work with no connection to the Mexico, notably Claire Zeisler’s ghoulish “Private Affair I” (1986).

Of the mass of ephemera in “Six Modernists” — including magazines, newspapers, and correspondence — the most interesting are preparatory sketches. Porset’s in particular illuminate the cleanness of her lines, the ideals she had in mind en route to her Butaque Chair, or her Tea Cart (1962), in which double vision becomes both rustic and useful. The rest is the business of historians.

Donald Trump himself is not here, never named; but he’s always here, fresh in the minds of anyone who watches the news or has a Twitter account. Reading about refugees and wrongful prisoners through a shared Mexican lens, it’s hard not to think of children in cages at the U.S.-Mexico border. It’s also notable that all six artists are women, another group Trump has repeatedly demeaned and victimized with impunity. Mind you, the show is interesting without Trump having anything to do with it — several aesthetically stunning moments plus a reasonably well-argued thesis statement make for a rewarding, edifying visit. But Trump is always here, and in light of that, “Six Modernists in Mexico at Midcentury” very politely, discreetly gives him the middle finger.