I woke up at 3:30 a.m. this morning to a barrage of texts and emails from friends and family in Louisiana with variations on the same message: I’m OK, but it’s worse here than we ever imagined.

Normally when I wake up at 3:30 in the morning I eat some tortilla chips and go back to sleep, but this time I felt uneasy. I opened Facebook and started to scroll down my news feed. My friends are a mix of art school students, cat-lovers, and activist-types in New Orleans. At 3:30 a.m., the art students and cat people were all asleep; the activists dominated 100 percent of my digital space.

Dozens of my friends traveled to Baton Rouge Sunday to protest the fatal police shooting of Alton Sterling — a 37-year-old black man — that took place last Tuesday. Coverage of Sterling’s death was immediately eclipsed in the media by the news the next day of an African American man killing five police officers and injuring nine more in Dallas. The national discussion shifted. Suddenly, the media was declaring that the country was in the midst of a civil war.

My friends in New Orleans mourned the violence all around, both physically and digitally. They solemnly, peacefully filled the streets around Lee Circle — a traffic circle encasing an enormous monument to Confederate General Robert E. Lee, which activists successfully demanded be destroyed earlier this year. I know all about the vigil because they tweeted it and Instagrammed it and posted the pictures to their Facebook walls. My friends commented that the vigil had been a beautiful testament and a powerful public space.

But that wasn’t how things looked in Baton Rouge. My feed at 3:30 this morning communicated a world of terror. One of my friends posted this video, which shows a thick mass of police in riot gear marching toward peaceful protestors and looking a lot like an army marching toward field combat.

Other friends circulated that video — it looped on my wall repeatedly all morning.

Max Geller, a friend and vocal political activist, posted a live feed of the streets of Baton Rouge after the chaos had started. He kept it going until he was arrested for standing on someone’s private property. (After the police ordered protesters to get out of the streets, they moved onto the sidewalks; as the sidewalks overflowed, a local woman gave them permission to stand in her yard, where they were arrested.) Another one of my close friends, Bob Weisz, posted this picture of Gellar being arrested to his Instagram:

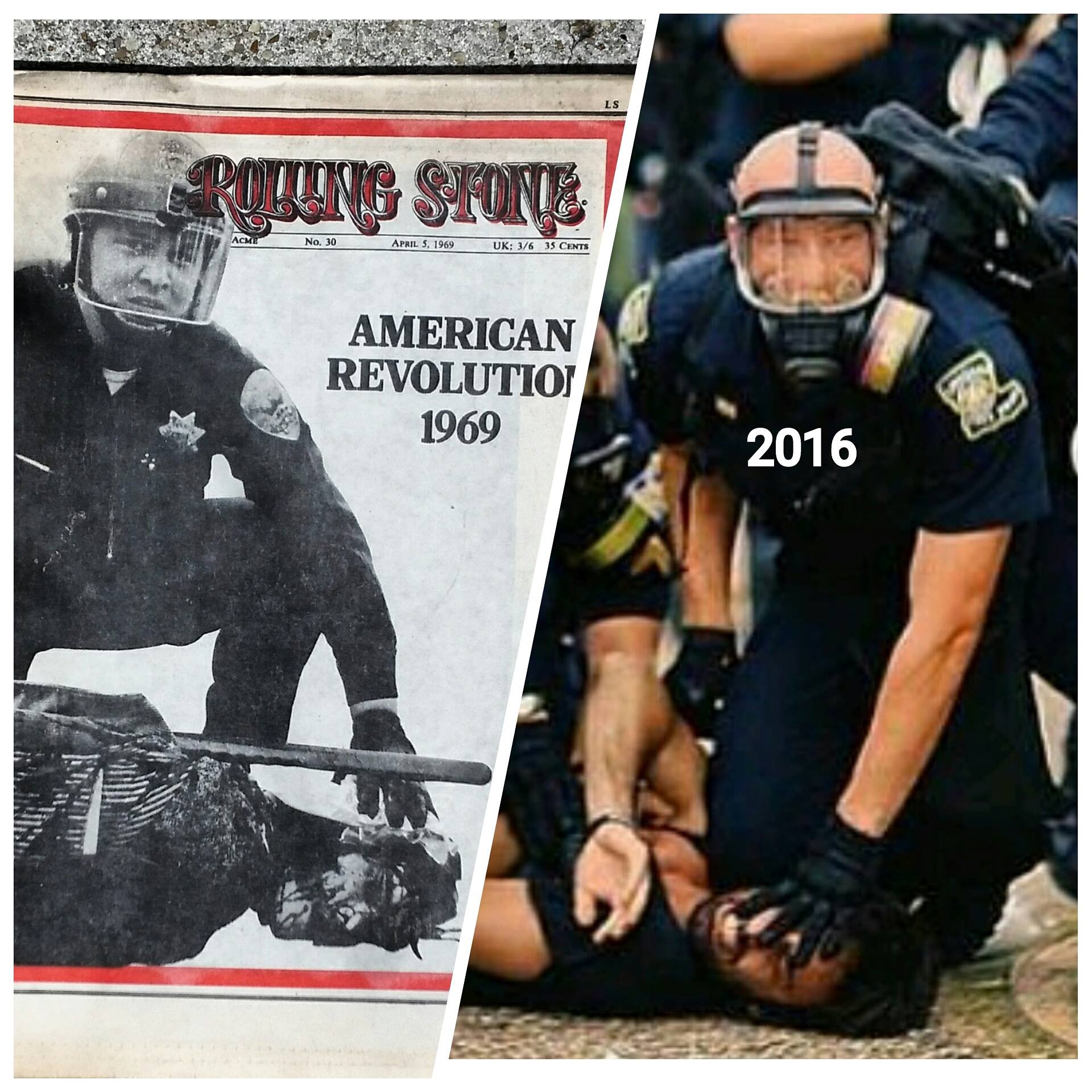

Weisz later posted that image alongside a cover from a 1969 issue of Rolling Stone Magazine:

He added this to the picture:

And remember, while this photo became very relevant to our friends last night, it’s BEEN relevant to almost every black and brown person alive in America, for their whole lives. That’s exactly what our friends were speaking out against. The pain you feel seeing this photo is a fraction of the pain felt by black and brown families across the nation for decades, for centuries.

It was difficult — as it is always difficult — to see people being brutalized by police officers. But I have to admit it was even harder to read the first-person accounts of my own friends, and to watch footage of their experiences. I couldn’t go back to sleep. I donated $150 to the Baton Rouge Bail Fund and waited.

I was waiting to read the official reports in the national news. I was waiting for the world to see what I had watched on my Facebook newsfeed. These images; these accounts; these videos were about to have an enormous impact.

But the report I was looking for never came. What came instead was an article titled “Dozens Arrested at Baton Rouge Protest, Police Say Protesters Threw Concrete.”

I watched a lot of videos of the police interactions with protesters. There were plenty of accounts available online from people who were there. Of the hundreds of people filming everything they could with their personal phones, not a single one caught footage of anyone throwing anything at a policeman.

While the article quotes police officers (one says, “The bottom line was this group was certainly not about a peaceful protest”), it doesn’t quote anyone else. There are no interviews with people who were arrested. There are no interviews with people who saw other people get arrested. There are no interviews with organizers, or with local citizens, or even with prominent members of Black Lives Matter. (Even the New York Times, which has also done a terrible job of reporting on protests across the country this week, did better in that regard.)

No one has so far come forward with any evidence that concrete was actually thrown — outside the statement given by police officers. (We all know that police officers are great at telling the truth.)

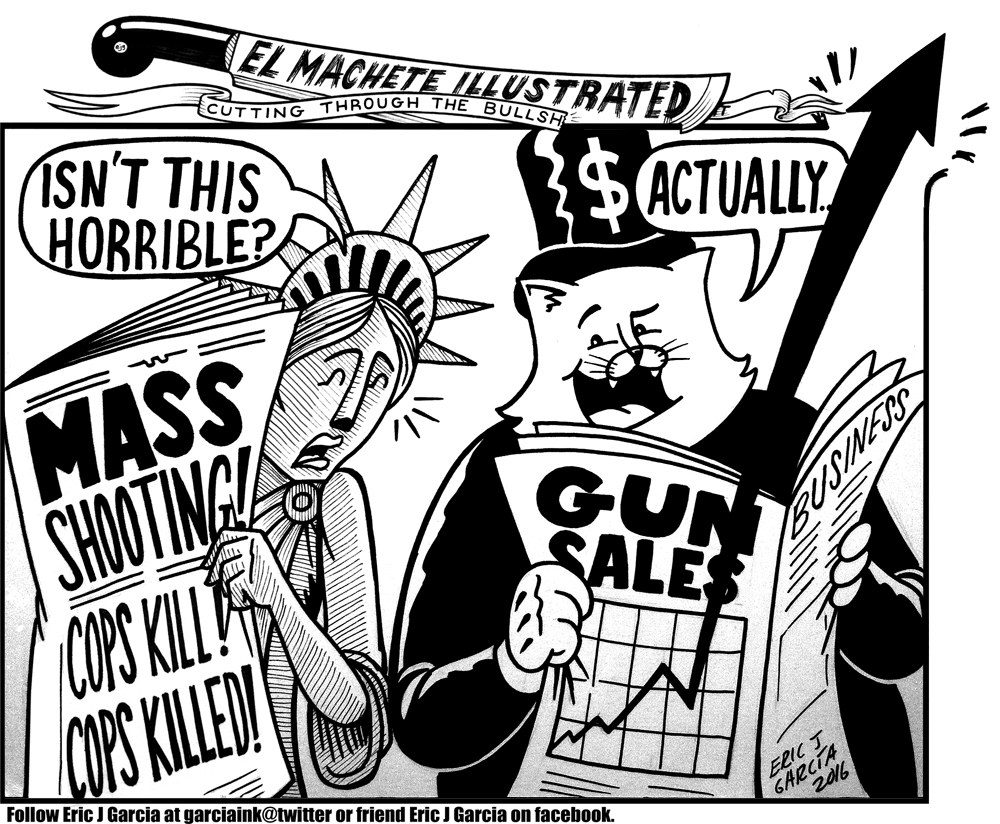

At the end of the day, my Facebook newsfeed was more journalistic, telling, and thorough than anything the national media gave up. (Clickbait sites nationwide did adopt this photo saying it “symbolizes last week’s protests,” but this photo is just a fraction of what went on yesterday in Baton Rouge.)

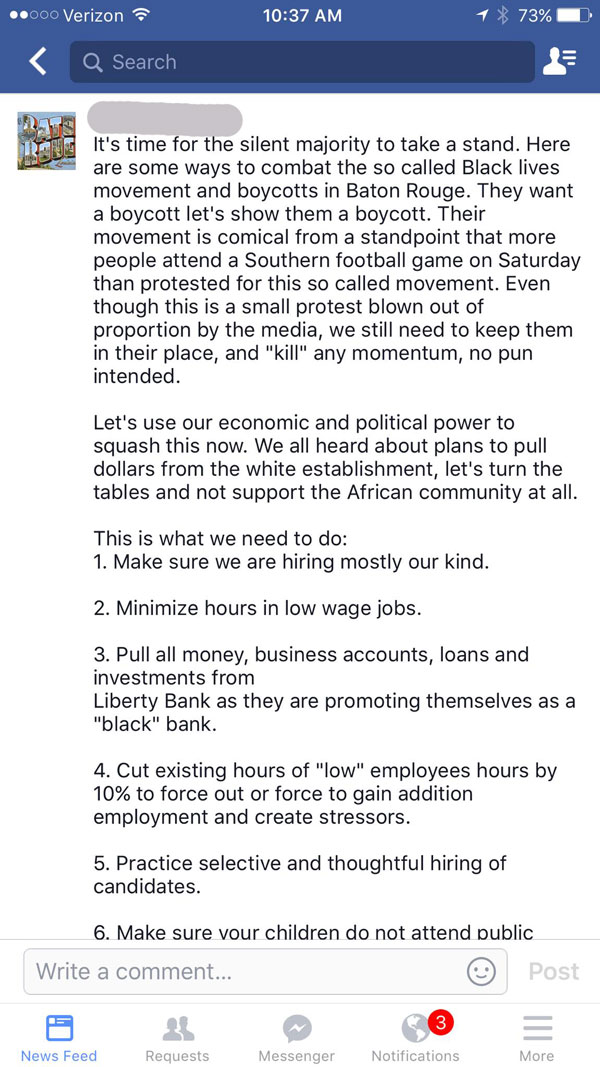

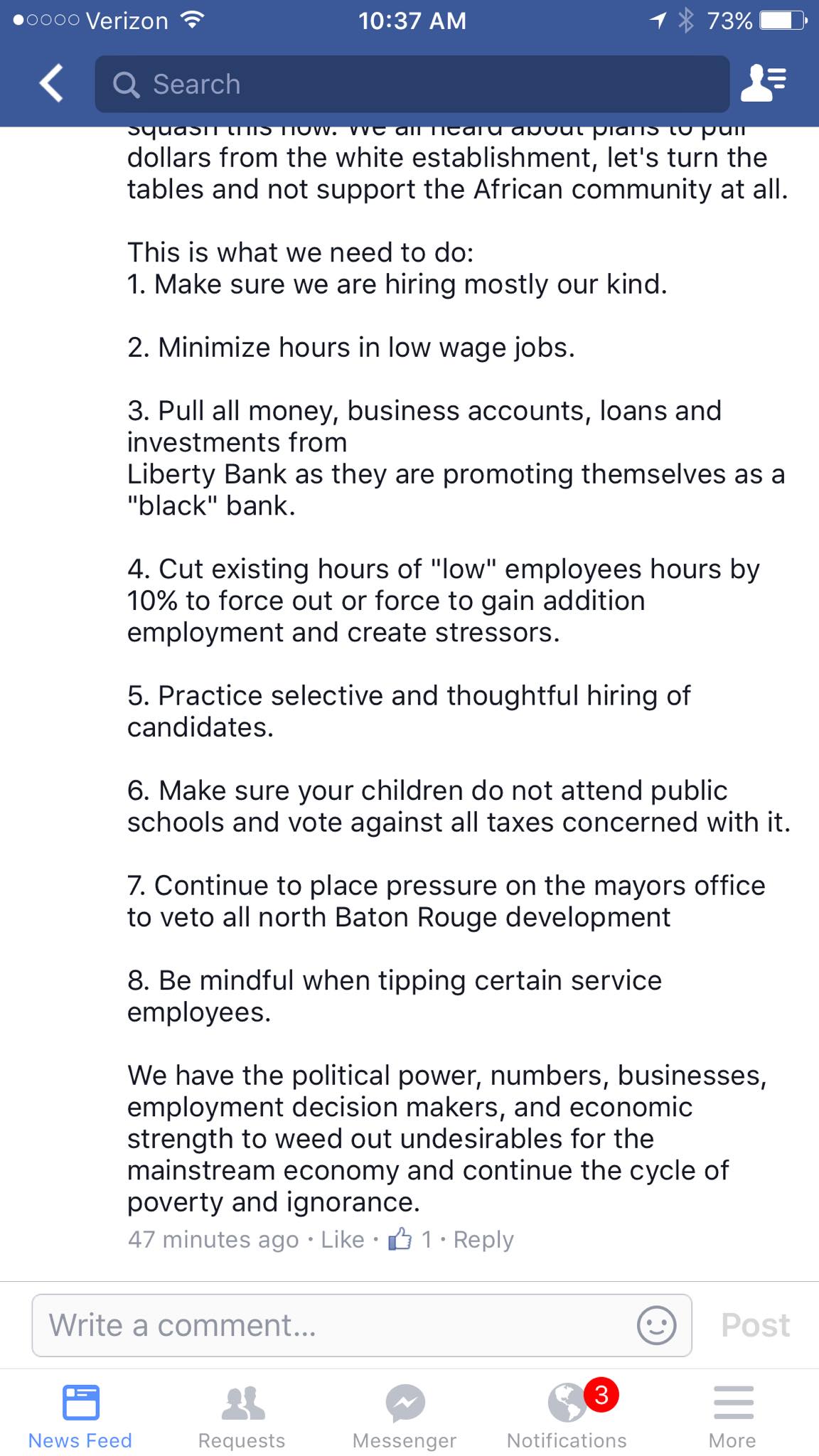

While it’s an enormous cliché to say that the mainstream media is unreliable, this continued failure to accurately report what is happening will become increasingly dangerous in a country that is becoming increasingly divided. Take, for example, this pair of screen grabs one of my friends posted on his own wall earlier today:

The complete failure of the national media — who, my friends report, were indeed in Baton Rouge, and had the capacity to capture a more complex narrative of what happened there yesterday — to report on this story is terrifying to me, and it should be to you, too. I can’t begin to imagine what else we’re not seeing or hearing that might change everything.