Lena Dunham Doesn’t Deliver

Actress, screenwriter, director and now essayist Lena Dunham cites former editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan magazine Helen Gurley Brown’s Having it All as an inspiration for Not That Kind of Girl, her first book. Though she picked it up at a thrift store as a novelty object, she was drawn to Gurley Brown’s attitude that happiness and satisfaction are achievable for anyone. Like Gurley Brown’s book, Dunham’s is broken up into sections that include Love

& Sex, Body, Friendship, Work, and The Big Picture. Dunham writes that the collection consists of “hopeful dispatches from the frontline of [her] struggle” to have it all. Yet, having it all is the book’s central problem. In casting a net as wide as the horizon, Dunham’s essays often fail to reach the depth and insight for which she is capable.

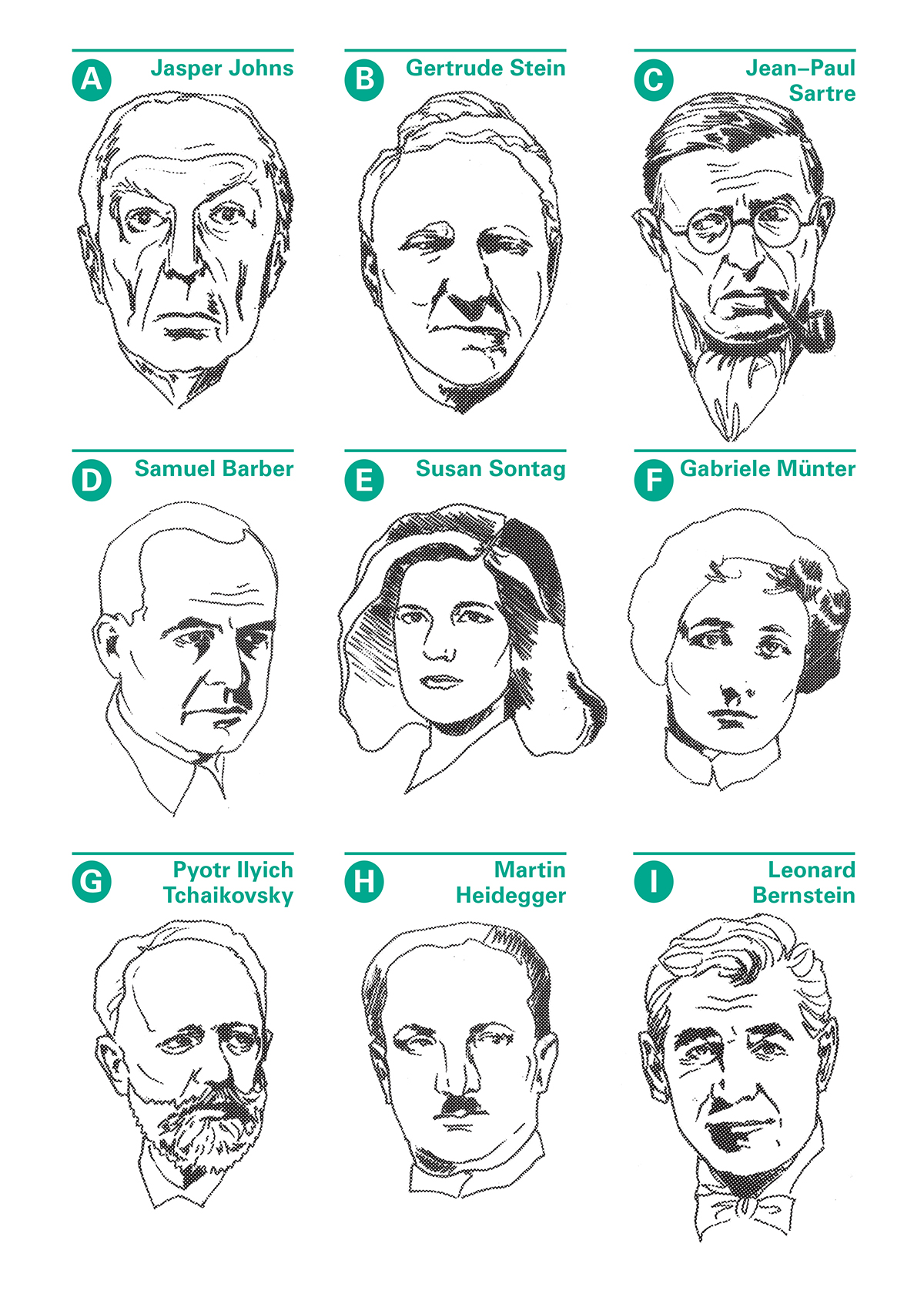

For those who have somehow escaped Dunham’s near-constant media presence over the past few years, she wrote, directed, and starred in two critically acclaimed films before the age of 25 and was then offered her own HBO show, Girls, to do the same.

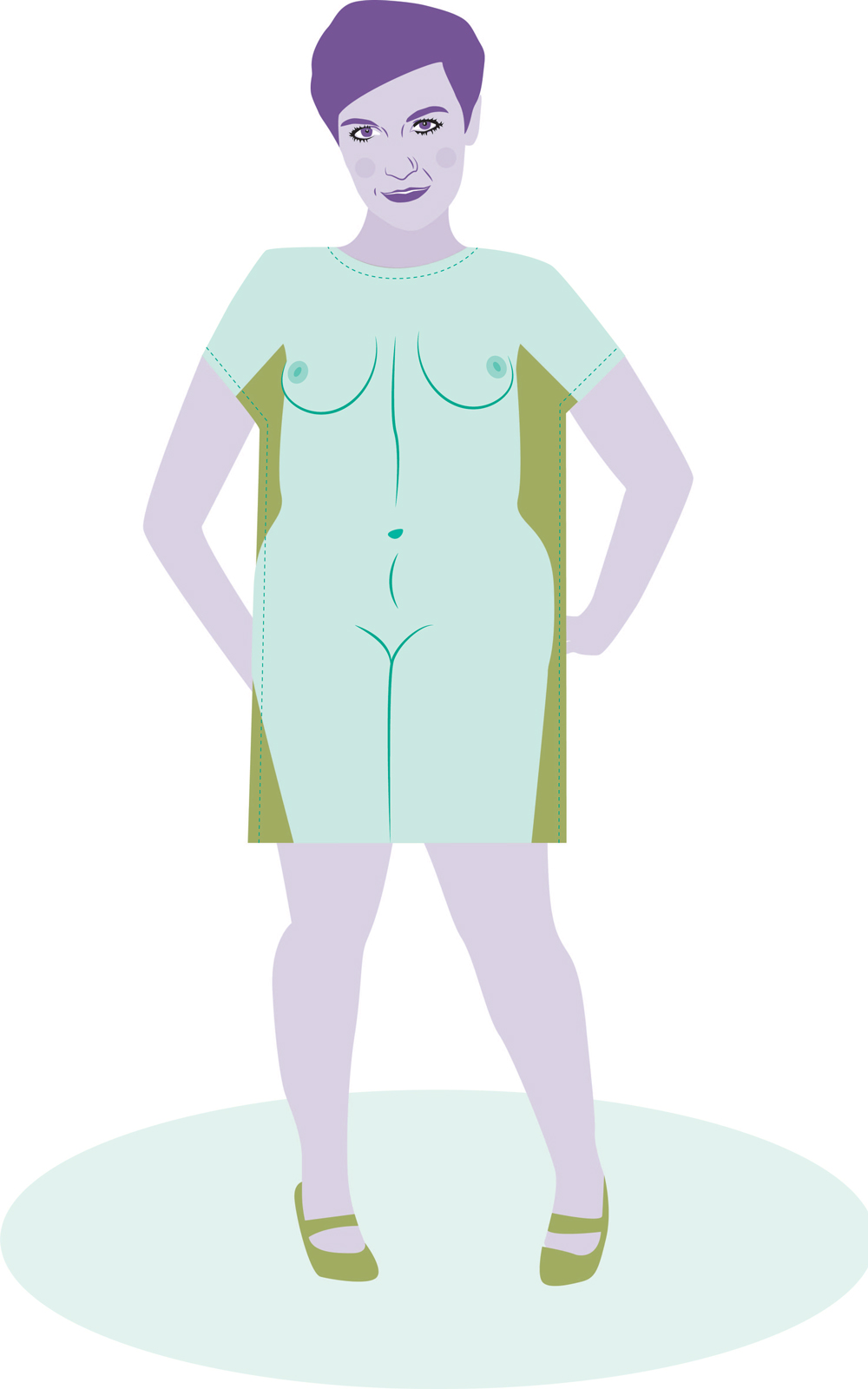

Dunham’s work often contains revealing, honest, and funny portrayals of her body, and this book is no exception. She tells us about her feelings of anxiety and disembodiment, of the pain in her vagina after rough sex. She tells us about discovering masturbation and compares sex to shoving a loofah in a Mason jar. While most of her body-centric anecdotes are important and necessary, some are overindulgent. An entire section of the book is simply a food journal detailing when and what she ate and how many calories were involved. I thought there might be a semi-obscured formal reason for its inclusion, as there is with the slightly more successful annotated email she shares, but there isn’t; it’s laborious fluff that should have been cut in the first round of edits.

&nsbp;

Though Dunham and Hannah, the character she plays on her show, Girls, are so very similar, their most important difference is that Dunham is self-aware where Hannah is not. In her book, Dunham is obviously conscious of her privileged upbringing when she remembers a friend in college who dismissed her as “Little Lena from SoHo.” Though that sense of self-awareness seems awkwardly absent when she tells other stories, like the one about her hosting a vegan birthday party as young teen that was covered in the New York Times style section.

I Didn’t Fuck Them, but They Yelled at Me is the name of the book Dunham’s going to write when she’s eighty, once everyone she’s met in Hollywood is dead. It’s going to be a vengeful tellall about the misogynistic treatment she had to put up with to be taken seriously. Though she doesn’t name names, she recounts plenty of examples of what her friend calls “sunshine stealers”: men who want not only sex but also to steal the ideas and vitality of passionate younger women in the industry. To them, women in Hollywood are “like the paper thingies that protect glasses in hotel bathrooms — necessary, but infinitely disposable.” Just wait till she’s eighty, she repeats throughout the essay. Then she’ll really be able to get back at them.

Knowing her talent as a writer makes the book’s shortcomings all the more frustrating. “I consider being a female such a unique gift, such a sacred joy, in ways that run so deep I can’t articulate them,” Dunham says. That’s a powerful statement with verity I don’t doubt but whose nuances I want to see. It’s frustrating that she won’t try to articulate something so important in a book she was paid a $3.7 million dollar advance to write.

Toward the end of the book, Dunham says that thoughts of death come to her at inopportune moments, like when she’s dancing or smiling at a bar. The anecdote is frightening and familiar, and certainly a relief from hearing about her vagina. Things are going well until: “I guess, when it comes to death, none of us really has the words.” Maybe I wouldn’t notice this if someone were to have copped out of a description only once, but this is at least the third time. To characterize things several different times as indescribable is lazy and vague and leaves the reader dissatisfied with an essay that otherwise could have been more interesting.

Overall, Dunham engages readers with her candor, idiosyncrasies, and humor, but fails to deliver at the moments that count the most. She often discusses the stories she can’t tell or the words she won’t share, but with so much nakedness — literal and figurative — drawing attention to the things she chooses to keep for herself feels at best disingenuous and at worst condescending. With so many of her cards on the table I have a hard time believing the ones she’s keeping to herself are as good as she claims. Or perhaps they are, but she’s not the person to articulate them. Or perhaps not yet. Maybe we just have to wait until she’s eighty.