Illustration by Patrick Jenkins

What does Art mean to Occupy?

“Our basic message is: the taboo is broken, we do not live in the best possible world, we are allowed and obliged even to think about alternatives,” philosopher Slavoj Žižek addressed Occupy Wall Street at Zuccotti Park on October 9, 2011. He located the occupation as the beginning of a movement, not the end, and urged his audience to expand political narratives, allowing for even a brief glimpse, some may say nothing more than a shadow, of a world beyond Capitalism.

The Occupy movement developed in the aesthetic realm, making it an important aesthetic contribution, even before considering its occupation of the arts and art-related activities. The notable conceptual and visual beginnings — with the Adbusters, call and the image of a ballerina perched on top of the bull near Wall Street — preceded and were somewhat independent from the physical occupations that later developed globally.

Beyond these fledgling moments there have developed various groups focused on artistic production for the movement as well as direct action against what are perceived to be the ills of the art world. These groups include the Arts and Culture Committee of Occupy Wall Street, http://occupymuseums.org/ and Occuprint, to name a few. While the Occupy movement may have aesthetic beginnings, the question remains, how can art help further develop the aims of the movement as a whole? How are these groups, and others, using art for social change?

The Beginning

The conceptual initiators of the movement — Adbusters editor Lasn Kalle and his colleagues — were not responsible for its materialization and had no way of anticipating how it would unfold. However, as William Yardley points out in his NY Times article “The Branding of the Occupy Movement,” they were responsible for developing Occupy as a meme.

“If you’re able to come up with a very sexy sounding hashtag like we did for Occupy Wall Street, and you come up with a very magical looking poster that seems to have something very profound about it, these devices push these memes, these meta memes, into the public imagination in a very powerful way,” the article quotes Kalle, explaining how he believes Adbusters contributes to the movement.

In the same New York Times article, Yardley notes that some people had been skeptical of Adbusters’ use of glossy visual media as an effective political tool. They questioned the ability of the advertising vocabulary to serve as legitimate cultural critique. This skepticism echoes a general distrust of art as a revolutionary tool.

The question of the political effectiveness of certain forms of representation is a crucial issue when concrete social and political change is the goal. To be sure, the movement didn’t actually begin until individuals congregated in specific geographical locations. Now, however, after the physical spaces that were occupied — Zuccotti Park, most memorably — have been cleared, the presence of the movement has shifted. While direct action and outreach are essential for political organization, could art fulfill an imperative for imagining an alternate world?

The Artist/Activist

“The idea was that we could open up a space for creativity or for free exchange of ideas,” explained documentary filmmaker and SAIC alum Marisa Holmes, a member and organizer of Occupy Wall Street. F Newsmagazine spoke with Holmes about the role of art within the movement a few months ago. She continued, “From the beginning, visuals and ideas were catalysts and they have continued to be in certain respects.”

However, Holmes makes certain to note the importance of direct action beyond aesthetics and image-making: “The question is how does art function in society and how can art be a way of life? In order for that to happen you have to confront the way that art is commodified and used as a tool of cultural status. … It is really about fundamental change; it is not about an aesthetic.”

Art and politics have had a prolific, if somewhat unsettled relationship in the United States. With the rise of the New Left in the 1960s, the nature of explicitly political art production moved to the foreground of debates surrounding the function of art in society. As Julia Bryan-Wilson outlines in “Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era,” artists began thinking of their labor in overtly political ways, turning their attention beyond the value of a specific artwork to the process of artistic production.

Art Workers Coalition and Art Strike in New York City were at the front lines of thinking about how art and artists could and should fit into society. However, the professional art world continued to function separately, and some would say at the expense of, the majority of working- and middle-class Americans. These divisions are what Holmes and other members of the Occupy movement hope to demolish along with the brutal inequities of the capitalist system. “The idea is that everyone is an artist. That creativity is a way of life not separate from society,” Holmes insists.

While artists have typically been at the forefront of popular uprisings such as the Vietnam War protests in the ’60s and ’70s and AIDS activism in the ’80s, some of the art coming out of the current movement is indicative of a growing professionalization of art-making. There are many art projects developing out of Occupy Wall Street created by professional artists and designers. Alternately, there are many representations including innumerable protest ephemera and Internet memes — such as “the pepper spraying cop” — that have contributed, supported and furthered the Occupy cause.

A collection of

Occuprint publications

From Cardboard and Sharpie to Photoshop and Beyond

In January 2012, Vanity Fair published a slideshow of visual and written propaganda made by and for the movement collected by the New York Historical Society titled, “The Revolution will be Graphic-Designed.” The slideshow includes leaflets, posters and manifestos. The Occupied Wall Street Journal mimics the design of the conventional Wall Street Journal’s layout.

The November 2011 issue of The Occupied Wall Street Journal was dedicated to protest posters, designed by artists such as filmmaker Chris Marker or the Internet group Anonymous. The edition of The Journal was a collaboration curated by members of Occuprint, a printmaking collective that posts original Occupy-inspired images from around the world on its website where their further use is encouraged.

“Our aim is not to produce a unified aesthetic, but to magnify the diversity within this movement,” states the Occuprint website. “We are not trying to create a new brand, we are trying to build a new life.” They have been successful in creating an archive of diverse images from around the world.

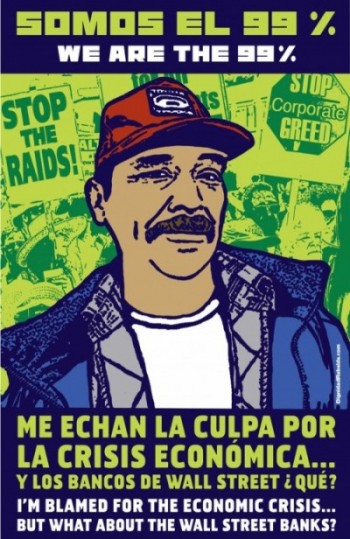

The posters in The Occupied Wall Street Journal range from a simple graphic of a raised fist marked by the “99%” logo in red, white and blue, to a detailed illustration of Mexican worker standing in front of a crowd of protestors. At the head of the poster it states, “Somos el 99%” and at the bottom it speaks for the worker, “I’m blamed for the economic Crisis…But what about the Wall Street banks?” The posters are diverse in image use and in message.

Despite its belief in diverse participation, Occuprint does not function as an organizing committee of Occupy Wall Street. It maintains a transparent but not quite democratic curatorial process. They do not hold open meetings and recognize that this runs counter to the horizontal structure of the movement. While they encourage submissions from anyone regardless of artistic training, they do have certain guidelines, like avoiding the use of imagery already associated with electoral politics or corporate branding as well as posters that don’t have a clear political message.

The use of posters in political movements is obviously not new. What is somewhat novel about this particular project is the ability to collect and distribute them easily and cheaply via the website, which is quickly becoming a vast international collection of Occupy-inspired graphics.

While Occuprint is an example of visual representation for the movement, other groups are focusing on economic and cultural elements of art circulation. Occupy Museums has garnered attention through its attempts to highlight economic inequalities in the art world by protesting outside of MoMA and setting up an alternative to the Armory Show in New York.

Chicago and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago

On March 28, SAIC undergraduate Emily Day pitched a tent and briefly occupied the 13th floor of the McLean Center. No one joined her. In fact, the only attention she garnered was from two school officials who told her to remove the tent or face disciplinary action in the form of a meeting with Student Life. Feeling defeated by a seeming lack of interest from her peers, Day packed up and moved on. To be fair, the performance was planned last minute and involved little to no publicity, but it was successful in pointing out a certain lack of enthusiasm within the school body.

Day was a member of the briefly formed Occupy SAIC group, which, at its height had about 20 to 30 active members and organized one tabling event, according to Day. When F Newsmagazine asked why she thought the SAIC student body was disinterested about forming an SAIC-specific group, she couldn’t give a definitive answer. She did express hope for a resurgence of general interest now that Occupy Chicago meetings are moving back outdoors from the relatively uninviting building at 500 W. Cermak, where meetings were held through the winter.

Much of the Occupy Wall Street sophistication both in organizing and in visual production is still yet to be realized in Chicago, where the movement has been smaller. The Arts and Recreation Committee of Occupy Chicago has focused on organizing outreach events and networking artists from around the city. Their most recent projects have included the formation of the Rebel Arts Collective and the event “Better Days Ahead: a cultural tribute to the memory of Troy Davis and Martina Correia.”

“What we started trying to do was to connect artists together to create a collective and work on projects that were based in Social and Economic Justice themes, but not necessarily have to interface with Occupy — not have to go to General Assembly or stand on street corners,” explained artist Trina McGee. F Newsmagazine spoke with McGee and Amy Buckler, both organizers within the Arts and Recreation Committee and its offshoot the Rebel Arts Collective.

When asked about the role of art within Occupy Chicago, McGee said, “Some days, we are the heartbeat and some days we are the left toenail of the movement. There is definitely a give and take. … Making art is a task and a commitment in itself. Within Occupy, people who are not artists forget that it doesn’t make itself. There is such a craving for it at times, and other times they wonder why we are spending our time doing this when we could be doing something else.”

Most recently the group focused on building a giant “wishing tree” that was erected for the Chicago Spring Festival on April 7. Public participation was central for the completion of the tree, which featured the hopes and dreams for a better world written on its leaves. Buckler explained the construction of the tree: “You can’t just say, let’s make a 15-foot tree out of paper-mache. We have to make sure it is safe and no one dies. If we can get it on rollers and find a very large person to push it, it will be legal. But, if we can’t make that happen it will be immobile and the cops will tear it down and take it away.” The ultimate purpose of the tree was to spotlight hope for a better world echoing Slavoj Žižek’s speech. According to McGee, “So many people haven’t even considered how they would want the world to change. When someone finally asks them, they either don’t talk, or they don’t stop talking.”

Ultimately, McGee and Buckler would also agree with Kalle’s sentiments about the power of visual arts: “One thing I hear frequently about Occupy is that it captured people’s imaginations, and that is one of the things that made it successful compared to a lot of other, smaller movements. It lit a spark, and that is something that art has the potential and the ability to do as well. It is a matter of, in a world where things are changing so fast, keeping on top of that spark.”