Interview by Dimitry Tetin

Dimitry Tetin: In your lecture you mentioned that you see the evolution of art from one frontier, to many frontiers, to no frontiers.

Arthur Danto: It’s everywhere, so to speak. One, many, every… What I was thinking is that everything is new. I was struck by the fact that you can do anything. And when you can do anything, its extremely difficult to think you are adding to a pool of any kind, that people can join. I noticed that a great number of young artists are involved in the autobiographical, where everybody’s life is at least that interesting enough to other people. And the art always seems to involve learning something about why the person made it or developed it about the person’s life.

For example: a guy who teaches sculpture in Las Vegas [Robert Wysocki], he makes Tonka Trucks. He makes these and enlarges them. So first thing you see if you go into the gallery are these toy trucks of a certain size. They are done meticulously, so they look as though they have been magnified. There is a lot of skill that goes into that. He doesn’t have them fabricated. The proportions are related to how large he was relative to that Tonka Truck at that particular time. It’s an index of his growth.

It is a work that doesn’t mean a lot to people from my generation, who really didn’t have Tonka Trucks. For anybody who grew up or is growing up now, it has a lot of meaning. It has a lot of meaning to people with boys: mothers of boys, or fathers of boys. The trucks have a kind of particularity and connection for them. I thought that it was an interesting work, interesting to look at. You wouldn’t know what it was about if you weren’t part of that culture or knew about that culture. The scale is personally a very important thing in this work. That is just one example of autobiographical work that doesn’t necessarily look like it. You would miss the meaning completely if you weren’t told about it. It came up in the discussion last night: Is it a failure if you have to be told? I think you always have to be told now, because everybody’s life is a little bit arcane.

DT: Do you think it is peculiar to the present condition?

AD: I think so. I don’t know whether it’s peculiar, but it seems to me that everybody is looking for something to make art out of, and at least young people. The first thing that suggest itself is their life. It’s confessional. So there is an immense amount of ingenuity. I think a lot of meaning actually becomes rescued. But you have to recover it. You have to find something out about the person. This is an example of the frontier being everywhere. You now have access to anything you need. And you try to find some way of rescuing it with meaning. And you can see what the artist is getting at. So you would go into a gallery and say well “That’s a really handsome piece of sculpture.” But it has a lot of meaning. I was thinking at that point about the idea that one is moving into aesthetics of meaning, rather than the aesthetics of form.

DT: In the introduction to the essay “After the End of Art” you write, “I think the ending of modernism did not happen a moment too soon. For the art world of the ’70s was filled with artists bent on agendas having nothing much to do with pressing limits of art or extending the history of art but with putting art the service of this or that personal or political goal.” Is that still the case in the contemporary situation?

AD: It’s not quite so much politics at this point. It does seem to be very much more personal. I think I was thinking about the point where modernism was pretty much over. I was quoting a memory by Eric Fischl at CalArts when he was asking, “What are we supposed to do with this at this point?” Students didn’t seem to know what to do in the ’70s. It seemed to me to be a particularly fluid moment. But I was thinking about the way, in the ’70s, the amount of artistic energy going not into a movement, but a curatorial agenda. In some way they were putting art in service of a political agenda. It was not exactly an artistic movement. It was a political movement that used art.

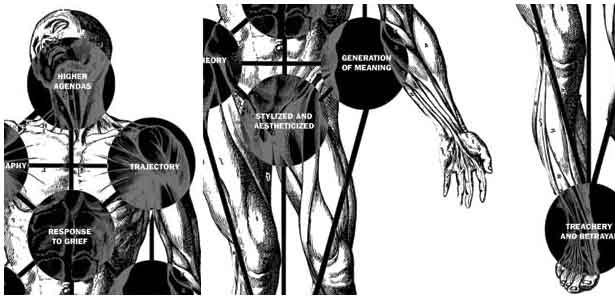

In trying to write a piece about a group show at the Brooklyn Museum, I began to go back to the graffiti movement. It began in 1971 and was over with in 1980. The entire effort was to get one’s signature on the side of the subway train. That was fame. It didn’t have any higher agendas. It began in New York. Some guy named Taki. He was writing his name and address: “Taki 183.” I walked out one morning and the sidewalks were covered with “Taki 183.” And then, bit by bit, people began to put their names down and then that began to migrate. But it hadn’t become spectacular. The unit was a signature across the entire subway. And it evolved into a code of writing. It was amazing to think that in ten years it could have gone from a scribble, “Taki 183,” to something like that. But the meaning of it was highly personal. There was a whole culture. The writers evolved, it was like the Renaissance. They evolved their entire culture: the notion of the guild, the meaning of the drip, masters, and apprentices, and a whole code: you shouldn’t overwrite on somebody else’s work, but you can negotiate. It was usually guys. There were girls, Lady Pink, four or five other women were involved. But it was still basically about getting your name up.

Michelle Zis: Do you think it was both political and autobiographical? The graffiti art?

AD: I don’t know how political it was. Jean-Michel Basquiat was somewhat political and he was really involved with black issues. For one thing, the writers were not all black. They weren’t even all ghetto kids. There were kids from Park Avenue as well. But I don’t even know whether it was art. I think that graffiti is part of what is now called, visual culture. I think that it was an exemplifying movement in that decade. There was that growing tendency of finding the frontier where you were. There was a certain amount of politics in the ’70s too. I don’t really think it was that way with the graffiti movement, as far as I can tell.

DT: Do you see art following its own trajectory, or responding more to a political, historical trajectory?

AD: That’s a tough one. I don’t know the answer to that. The war was winding down, maybe the artists were responding to that. There may be larger theories available but I don’t have one.

DT: I think of Eric Fischl, “Tumbling Woman,” which was a particular response to 9/11.

AD: It was. It was not accepted. People didn’t like it in New York. He displayed it in Rockefeller Center.

DT: They had to cover it up.

AD: In the end it was a bad idea. I tried to write a couple of pieces about 9/11 in The Nation. What was 9/11 art all about? A lot of people thought there was no way in which they could deal with it artistically. I found a number of people who were but it wasn’t exactly what you thought it was going to be. What Eric was doing was not the way in which people were responding to it.

A year afterwards, I started asking artists what they were doing. I remember, when 9/11 happened somebody called me, said he was from The New York Times, he said: “What is the art world going to do about this?” I couldn’t imagine that the art world was going to do anything about it. Some people thought there was no way in which they could cope and other people responded by making art. There was a part that I began to think was characteristic of 9/11. Lucio Pozzi is an artist. He teaches at the School of Visual Arts. He lives on Mulberry Street. He went out and he took photographs, one after another, of the smoke on Mulberry Street. They just look like blurbs. But he did those photographs and mailed them out to friends. That for me typified a genuine 9/11 response.

Audrey Black is a realist artist. She is a very political person. She went down, she tried to help. There was no space for her. But she did what she could. Then she decided she would go out to Montauck (which is the end of the land) and just paint boats. That was a way of dealing with grief. And Eric’s was not like that. I think Eric is a wonderful person, politically motivated kind of person. It was just an unfortunate choice. I think everybody felt that. That was not what they wanted to see. It was the case of somebody trying to deal inadequately with an event and the question, the larger question, was how do you deal adequately with 9/11.

DT: I think at that particular point, a lot of artists felt they had to respond to a moment in history.

AD: Yeah, but paintings with people jumping out? I don’t think that was where it was at. What amazed me about 9/11 was the instantaneous response of people: building shrines all over the city. That was most astonishing. Nobody told people how to do it or what to do. We didn’t go out for a couple of days. When we went out, they were everywhere you went, along all the staircases, windowsills…There is a park on the 106th street where West End Ave begins and Broadway cuts across. It is not a pretty park, it is a little triangle of land. On every surface there were shrines, candles. I should have taken photographs. I was really overwhelmed by it. I thought that what ordinary people were doing was probably better than what any artist could think of. I don’t think artists were able to do anywhere near what people were doing.

To have a genuine artistic response you have to have some of the qualities that belonged to the shrine. They just vanished. A friend of mine made a wonderful work. There were posters of people who had disappeared all over town. In the subway on 42nd Street the columns were covered with photographs, and in Union Square, a lot of photographs. This guy started photographing the photographs. What happened to the photographs? To see the photographs go through a kind of second death. That was a very powerful statement. Just the rain, whatever the city deposits. I thought we don’t really know a lot about the human mind when it comes to dealing with these kinds of events. We began to see it, and we see it more and more: the death of Princess Di, the piling up of teddy bears. It is a little bit like voices. And everybody is an artist. People have to do something and there is no real practical place. They build these things that embody some conception of beauty and appropriateness and ritual. It is a way of everybody being their own artist in that way, and the artist themselves being their own artist.

DT: The lecture you gave at the Art Institute’s Fullerton Auditorium was in the context of educating artists to be artists…

AD: I thought today it is a different question. I talked about, what seemed to me, to be a big change. We don’t know where it is headed, yet. The rise of the art fairs raises huge problems for galleries. Is the gallery going to be able to survive? They do an awful lot of business at these things and artists need that. I talked to some of the dealers about how many of these art fairs they can manage to go to, may be two, three or four. Certain ones they have to go to, like Miami, Basel, the Armory Show. But it is changing the gallery. Everybody has to make money. So, the student coming out of the art school these days with this debt, and here are galleries that are looking for work and the fairs that are making it possible. But what is it all about? That seems to be an interesting question.

DT: You also mention that in the contemporary art world skills and craftsmanship are not…

AD: …not the big deal.

DT: Not taught.

AD: I don’t think so…

DT: Where do you see the art school in this world? What is the art school supposed to do now?

AD: I think that if you are a student in an art school you have some idea of what you want to do as an artist. You don’t say, “Well, I just want to paint.” Usually there are certain works that you want to achieve. I don’t know where you go beyond that, what an artist’s life is going to look like now. You got these ideas you are going to start making, the art school is the atmosphere where you are going to make these things.

The generation of meaning seems to be what people are after. Something that puts lives into perspective for people. So at the end, that is not a lot different from what was going on in Greece. You go to the theater. You see what happens with husbands and wives and heroes and so forth. It got more and more realistic. In a sense, none of those guys went to school. There was a reason why people went to the theater it wasn’t just entertainment. They were interested in the kinds of things you read about in the newspaper: women and children and jealousy and treachery and betrayal.

DT: The performances were always stylized and aestheticized…that was also an attraction for the people.

AD: But then they got lost that way. You get to Euripides, there is still a chorus. You have to have somebody to comment, to explain to the viewers what is happening. You have to get the action across in some kind of way. The woman confides in her maid. The hero confides in his lieutenant: “This is what I want. This is why I have to do it. I have this problem in dealing with my father’s murder.” I think they got less stylized.

DT: Where do you see the role of the aesthetic in contemporary art? Do you see the generation of meaning as the primary goal of art?

AD: That’s what we need. Hegel had this idea, what he called “Absolute Spirit.” Spirit tried to find out what it is, what is its nature? This kind of self-consciousness, self-awareness, why we got it, what does it mean? Hegel thought there were three activities that exemplified what he called “Absolute Spirit:” Religion, Philosophy and Art. Three alternative forms of dealing with the same issues, in which people worked out the meaning of their lives. And I think at this point, philosophy is certainly not doing that for people. Religion seems to be doing it, but it is very ritualized, that’s what you talked about–stylized. It is attempting to force everybody into certain fixed positions. So in dealing with the individuality and the kinds of questions that people come across art is a way of doing it. I think that is why people feel as though it got that kind of power.

That is the line I am trying to follow at this point. I don’t know how else to do it. What is it for? Certainly not to give beauty. In 1925, when they set up the Guggenheim Fellows, it was for two things: for people increasing knowledge and for people producing beauty. But nobody thinks of art that way any longer. If that was true the production of beauty would be enough to justify people giving money for a year’s work. Now you’ve got to find some other answers. Beauty is not what anybody is doing. I think producing meaning is a style.

Arthur Danto’s forthcoming book is: Unnatural Wonders: Essays from the Gap Between Art and Life.

May 2005