Unbound: Contemporary Art After Frida Kahlo at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

It’s been 60 years since Frida Kahlo died, and her fame has grown tremendously among arts connoisseurs and the greater public alike. Unbound: Contemporary Art After Frida Kahlo, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (MCA) is definitely surfing on that popularity wave. While it condemns the fact that “she has been turned into a stereotype of Latin American Art,” the MCA uses her name as a crowd-drawing and money-making pretext for an exhibition that has very little to do with her or her work.

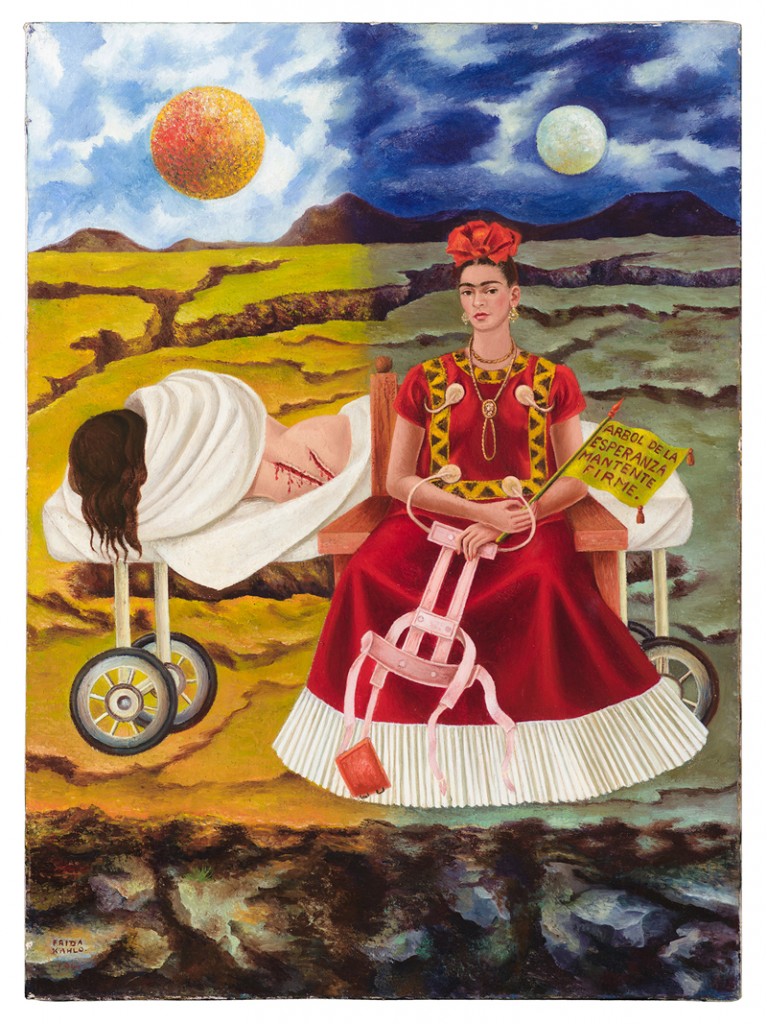

Frida Kahlo, Arbol de la Esperanza (Tree of Hope), 1946. Private Collection, Chicago. © 2014. Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago

The exhibition has four main themes, presumably epitomizing Kahlo’s work: “The Performance of Gender,” “Issues of National Identity,” “The Political Body,” and “The Absent or Traumatized Body.” Although all of the artworks selected for this show are of outstanding quality, their relationship to Kahlo or her work is, in many instances, nonexistent. Worse, some of the descriptions of these sections seem to acknowledge that these selections are random, to say the least, and some of the interpretations of Kahlo’s works are debatable. It is true that in its statement, the curatorial team does not claim that the works presented would resemble those of Kahlo. Rather, the purpose of the exhibition is to highlight the relevance of the themes she worked on and how they anticipated contemporary artists’ concerns. But these themes are vague, and the descriptions are broad generalizations that could apply to any other artist. Why choose Frida Kahlo?

“Issues of National Identity” is problematic from its very description: “… many [artists] seek to be defined by their art, not by political borders — unlike Kahlo, who strongly identified as Mexican.” Here the curatorial team is explaining to visitors that some of what they are about to see has nothing to do with Kahlo, and is actually in complete opposition to one of her characteristic themes: the love for her country and celebration of its unique roots. In “The Absent or Traumatized Body,” there is an element one could clearly identify with Kahlo: physical trauma. Who knows whose idea it was to add “absent” to this section, but if there is one thing that Kahlo isn’t in her work, it is absent. Valeska Soares’ work — a marble sculpture of two pillows in which the imprint of a head is visible — while beautiful, is completely out of place; the connection between Orozco’s Hand-ball (2002) and Frida’s work might only be the fact that they are both Mexican, and that is not good enough a reason.

Thankfully, José Leonilson’s self-portraits and Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (The End) (1990), which illustrate the traumatized body in an original and poignant way, save this section, together with Ana Mendieta’s Silueta series (1973-1980) and their more obvious relationship to Kahlo’s Alla cuelga mi vestido (1933). The theme of the traumatized body could have been a whole exhibition in itself, and it is a shame that the MCA didn’t see this.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #153, 1985. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Gerald S. Elliott by exchange. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago

“The Political Body” is a section dedicated to art as a “critique [of] historical injustice and oppression,” a vague concept that almost all artists have addressed at some point in their life. The MCA connects it to Frida on the basis that she was a fervent defender of communism, and therefore politically engaged. That seems to be a good enough reason to exhibit Sanford Biggers Quilt #24, a critique of the legacy of slavery and racism in America. Try as I may, I can’t remember reading about Kahlo’s involvement with either of these issues; but the most confusing choice of artwork has to be Rosângela Rennó’s red-saturated photograph from the Vermelha (Militares) series, representing a young man in military clothes. It makes sense because, you know, it’s violent, red and political, like Frida?

“The Performance of Gender” is the marketing icing on top of this opportunistic cake. Frida Kahlo is trending, gender issues are trending too, let’s kill two birds with one stone. It is true that Kahlo’s work and life have questioned traditional representations of gender, and to be fair, this topic also could have been the sole theme of an excellent exhibition, but once again some of the works completely miss the mark. Martin Soto’s Luminous Flux (2010) is a great piece, but doesn’t correspond to the MCA’s characterization of it as “[challenging] notions of gender by working with accessories and items of clothing commonly associated with femininity, while engaging with the history of representations of sexual desire.” How is making vagina-shaped creations with pearls and heels, paired with a video of the shadow of a woman taking her clothes off in a lascivious dance, challenging notions of gender? And how can it possibly connect to the way Frida represented femininity? Louise Bourgeois’ She-Fox (1985) limits the damage. The sculpture, true to Bourgeois’ aesthetic, displays rawness and physicality, mixes animal and human qualities, and emits both motherly and sexual energy at the same time.

Among the other works in this section, Julio Galán’s La Muerte morirá cuando pasemos a la vida eterna (2004) and Lorna Simpson’s She (1992) easily found their place, while the relevance of Jack Pierson’s presence is questionable. He never cited Kahlo as an inspiration and it’s not evident how portraits of young gay men — as beautiful as they might be — relate to Kahlo. Rather than a transcendence of the female/male dichotomy, Kahlo’s work addressed misconceptions or limited conceptions of femininity and power, and that is an element the exhibition fails to highlight.

Frida Kahlo, La venadita (little deer), 1946. Private collection, Chicago. © 2013 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The coup de grâce in this exhibition is in the poor treatment of Kahlo’s work. The only two paintings by the artist actually on view in the space come from a private collection from across the street from the museum. If you are naming an exhibition after an artist, don’t you think you ought to go a little further than 600 feet to source some of their work? Not only did the MCA not make efforts to acquire relevant artworks by Frida Kahlo, it did not do enough research on the ones they have on display. In the description of La Venadita (Wounded Deer), the MCA highlights the idea that the antlers on Kahlo’s head “suggest a simultaneous presence of masculine and feminine characteristics.” This detail appears as a desperate attempt to connect the painting with the thematic chosen for the exhibition. The description also mentions different religious symbols in the work: Christian, Pre-Columbian, but most interestingly, Buddhist, because the word “Karma” — or rather, “Carma” — appears at the bottom of the painting. As Helga Prignitz-Pova beautifully explained in 2008 in Frida Kahlo: Sadja, Carma, y el venado herido 1946, “Carma” isn’t Kahlo’s misspelling of “Karma,” but “Sadja” written in the Cyrillic alphabet. “Sadja,” “perdiz” in Spanish and “partridge” in English, is an affectionate diminutive the Mexican artist had chosen for herself. Of all Kahlo’s paintings, so many works could have been more clearly connected to the themes selected for this show. It’s a shame that the interpretation of Kahlo’s paintings suffered in this attempt to justify the exhibition’s themes, and it’s a shame that there are only two of her works.

Shirin Neshat, Turbulent, 1998. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Susan and Lewis Manilow. © 1998 Shirin Neshat

Unbound: Contemporary Art after Frida Kahlo is a waste of talent. The works are beautiful — some of them, such as Shirin Neshat’s Turbulent (1998) are breathtaking — but most of them have no relationship to Frida Kahlo, and you end up disliking them for the mere fact of being there. If the show had focused on only one of the themes, if it had really dug into one specific idea and have made relevant connections with Kahlo’s work, it would have been a success. Unfortunately, the MCA went for a bunch of general concepts such as duality of self, gender, body, politics and tried to mix them in one confusing show.