When thinking about what truly has happened to “digital art” since the 1990s, it becomes clear that much of new media art is not merely technology for the sake of technology, and much of it has confronted our dependence on consumer technology. While countless Internet-based artists today are more than willing to cynically critique the hollowness of how we think, speak, and process our lives through commodified digital technology, very few are willing to hold convictions and create true confrontation, disruption, or politically-charged tensions between their work and oppressive power structures in society. In contrast to current trends in new media art, the politically engaged Internet-based work of 1990s artist collectives and the contemporary Angolan new media artist Nastio Mosquito show that creating a pressure between art, aesthetics, technology, society and politics is a project that needs to be resuscitated.

In the 1990s and early 2000s there was a wealth of artist collectives like 0100101110101101.org (Eva and Franco Mattes), Electronic Disturbance Theater and RTmark, who employed the Internet as a tool to create direct confrontations with ideological, political, and social issues. These groups used the Internet as a form of tactical media that could be used as a temporary outlet for activism and sociological/political disruption. For instance, in 1998 Electronic Disturbance Theater initiated a flurry of DDoS (denial of service) attacks on the websites of former Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo, former U.S. President Bill Clinton, and the Mexican Stock Exchange, in support of the revolutionary leftist Zapatista group of Chiapas, Mexico, who were facing government coercion. In a similar spirit of intervention into issues of power structures, political imbalances, and social injustice, RTmark (who would later become the political-provocateurs the Yes Men) created pieces like “GWbush.com,” a convincing mock-website of George W. Bush for the 2000 presidential election, which incurred numerous cease and desist letters and provoked Bush himself to claim that “there ought to be limits to freedom.”

Sadly, the use of Internet art as a tool for societal and political provocation has gradually decreased. While it would be a misstatement to essentialize the diverse practices of artists working through new media or the Internet today, there are large numbers of contemporary web artists who would rather dabble with the permutability of digital files, the meme of painting, or cgi Greek sculptures as an aesthetic rather than imbricating art, and the possibilities of the new media, with real political and social engagement. Aside from these artists, there are those more concerned with critiquing Internet culture (personal cell-phone photos, memes, YouTube clips, advertising, etc.), commodities, and mass culture with ironic humor, like Jeff Bajj, Rachel Lord, and Nick Demarco (to name a few). Even so, there seems to be a divide between these artists and those who do not identify themselves as artists, like hacktivists, and those orchestrating Internet attacks on opponents of free speech and digital rights through the message-board site 4chan.

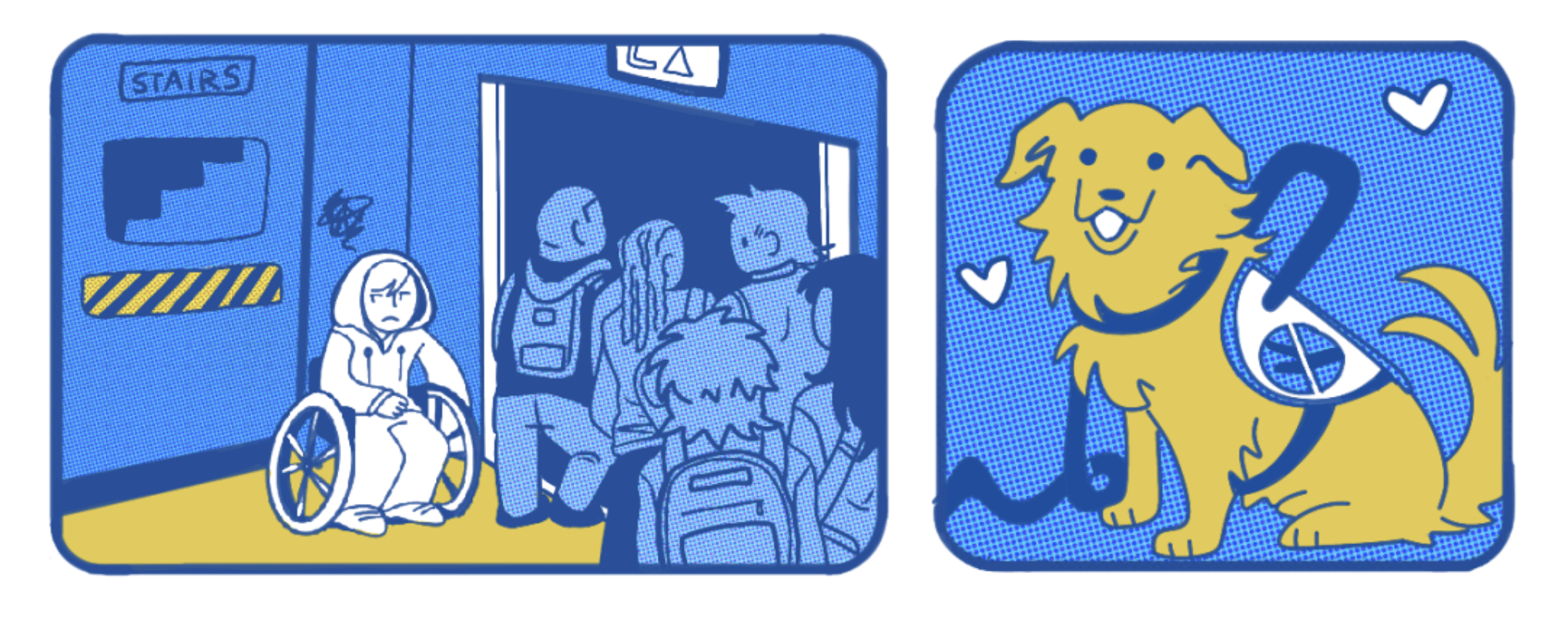

While the work of most artists dealing with commodities, kitsch, and Internet culture through humor is highly entertaining, and exactingly illustrates how we “think, see, and filter affect through the digital,” their work runs the risk of becoming non-confrontational and complicit with the objects of their critiques. Rarely do any of these artists use the topics of Internet or commodity culture as a means to interrogate, engage, or create sustained critical tension between their own work and the ever-present power imbalances or social injustices (such as those between class, race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, disability, etc.) that underpin our lives. Though political and social problems have only increased or become even more complicated (such as the 2008 economic crisis and ongoing U.S. military involvement overseas), there seem to be few artists explicitly addressing these problems through the use of the Internet and digital technology. It appears that creating real agitations or political/social disturbances have become a taboo subject for many contemporary web artists exercising what Hal Foster would term “cynical reason,” in that the cynics know their beliefs are false, but hold on to them to protect themselves from contradictory demands.

In an even more extreme avoidance of social or political concerns, there are some U.S. net artists who ironically fuse themselves with the commercially-driven aspects of the Internet. Troemel’s 2012 essay “Art After Social Media” precisely describes the phenomenon of artists who use aggressive self-branding through social media to accrue social and cultural capital. Though his piece does not specify names, it would seem that the two most flagrant Internet-based artists embodying this type of dandyism are Parker Ito and Ryder Ripps. Through cynical self-commodification, Ripps and Ito drain their work of deep political and socially concerned content, as did Andy Warhol and Jeff Koons.

Both Ito and Ripps take the promotion and fashioning of their undifferentiated online and real life personas as the main subject of their work. In dual display of quasi-critique and embrace, the otherwise permeable boundary between irony and reality is completely liquidated. Though Ripps’ body of work like “Ryder Ripps Facebook,” a downloadable archive of his Facebook page up to 2011 is almost self-explanatory, Ito’s most recent piece “Parker Cheeto: The Net Artist (America Online Made Me Hardcore)” seems to perfectly encapsulate their shared ethos. With a textured graphic of an America Online logo and a conglomeration of words, Youtube clips and kitschy graphics, the web page begins with an altered line from Prince’s song “Let’s Go Crazy:” “Dearly beloved, We are gathered here today to get through this thing called life/the Internet.” Viewing the internet as an all-consuming platform that allows no differentiation between itself and life outside it, the text continues, “If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to photograph it with their iPhone while simultaneously uploading it to Tumblr, Facebook, Flickr, Google Reader, Instagram, Twitter, and Delicous does the tree really exist?” To which he responds, “Only if the photo gets more than 10 likes, 5 reblogs and 2 RT’s.” In the hyper-awareness and self-marketability afforded by social media, Ito narcissistically presents his identity and work as only viable in terms of how many arbitrary likes, reposts and views it can achieve. A YouTube clip on the page metaphorically conflates his self-aggrandizing identity with a sack of fast food — he waltzes into an apartment full of hip 20-somethings (whom he greets as “My children”) and presents them with a bag stuffed full of McChickens, in which everyone then partakes.

While their grotesque technophilia parodies commodities, artistry, capitalism, and our digital media-induced obsession with promoting and constructing our personas through social media, both Ripps’ and Ito’s work stops at these issues, failing to funnel this narcissism into art that would confront more pressing socio-political matters. In the essay “All I am is a Son of the Cold War,” Professor Delinda Collier analyzes the disarming work of the Angolan artist Nástio Mosquito, who similarly presents his video work through social media and iPhone applications with a liberal amount of irony, technophilia, and narcissism. But what is most notable about his work is not merely the fact that it addresses the split subjectivity and disintegration of critical distance associated with digital media. Instead, his work resolutely achieves all of this while examining, interrogating and critiquing specific historical, political and ideological legacies of his context in South Africa.

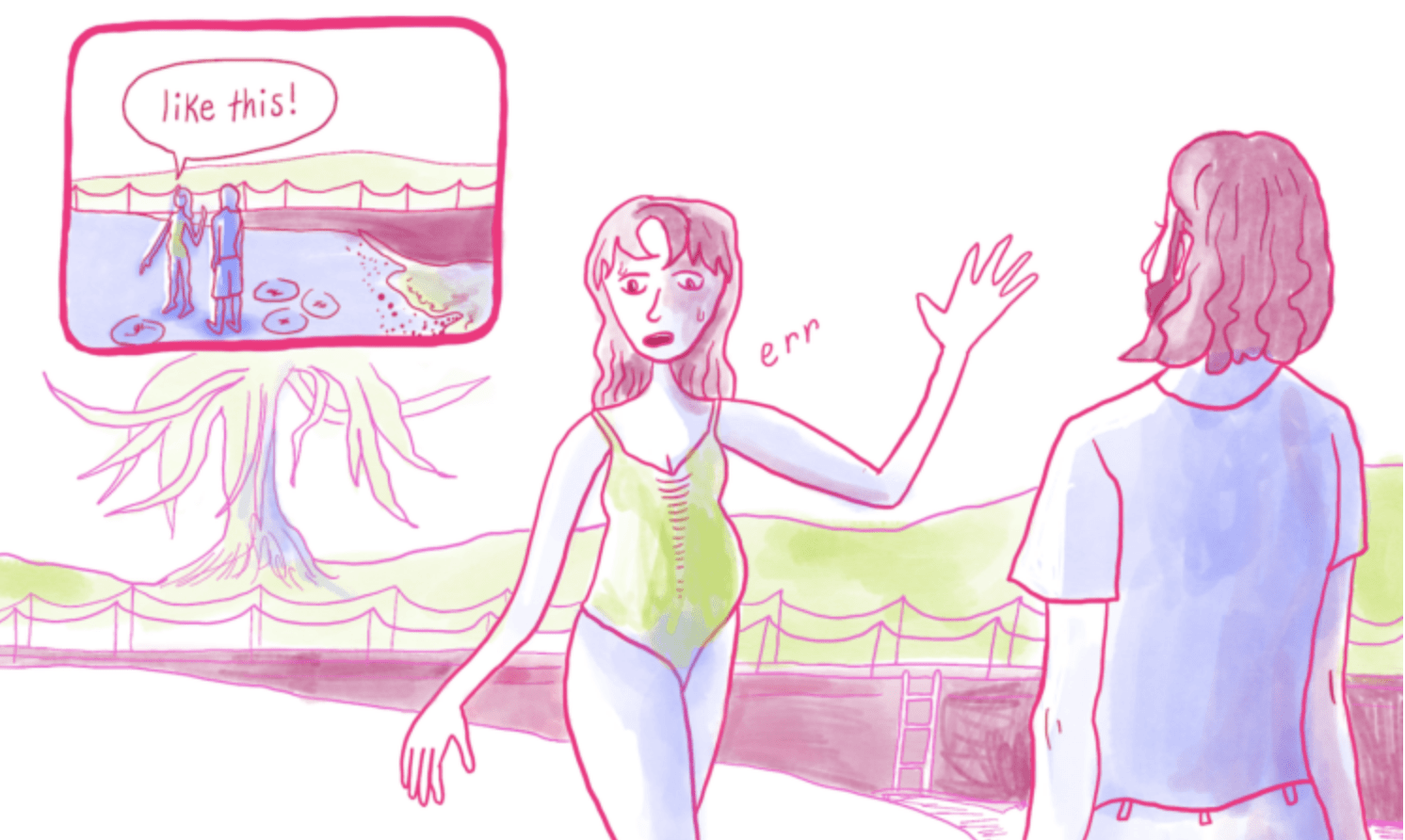

In multiple video pieces like “Continent” or “Fruit & Juice,” he addresses a wide array of topics like the hollowness and failure of neo-developmentalist rhetoric, urban poverty, and the lost promises of Marxist ideology. In the piece “Fruit & Juice,” Mosquito lampoons representations of poverty and “Africa” by impersonating a substance-dependant “sociologist” in Joubert Park, Johannesburg. As this “sociologist,” Mosquito proceeds to both conceal and aestheticize the destitution of Johannesburg by examining a huge pile of fruit on the street. He exclaims, “There is nothing wrong with this area. It is clean! And it’s productive.” Mosquito uses disarming irony and self-promotion as a tool to question and probe the social and political aspects of his context, while in both Ripps’ and Ito’s work the process becomes so self-serving that it prevents deeper forms of critical consciousness outside the narcissism of its author and the way we fetishize and promote ourselves through technology. Nastio’s work embraces a contradiction between commitment and narcissism, existing both as a direct engagement with harsh socio-political realities and as a parody of a modern media-obsessed public.

If anything, the work of the artist collectives of the 1990s and the work of Nastio Mosquito prove that artists can exploit new media and the net to realize substantive interventions within society and culture. Rather than using art for purely political means, or engaging in a more cynical surface-level critique of capitalism and new media, Nastio’s work realizes a mode of creation that is at once historically, politically, aesthetically, and socially oriented. If the Internet is still able to present a slightly less market-driven space for practice than gallery circuits or the contemporary art institutions, it should be disconcerting that much contemporary Internet-based art and new media work is willing to abandon the idea of deeper political or social involvement through artistic practice. The Internet and new-media are productive fields to test the borders of socio-political opposition with mass audiences, and if large amounts of net artists today are willing to refuse this onus, then they run the risk of denying the full critical potentials of the mediums themselves.

it seems this author only knows my facebook download piece.. which really is more reactionary towards rhizome asking me to make a work available for download.. trying to consider how relevant downloads even are in an age of the stream.. i made my facebook downloadable inorder to prove the stream is irrelevant because i knew no one actually gave a fuck about downloading my facebook.. regardless, the internet is a great idea for transferring ideas because i have no work for sale.. only some ideas you can try to understand.. or not.. whateves.

opps.. edit “norder to prove the DOWNLOAD is irrelevant” (not stream)

http://2013inter.net/napr

I thought this was a really good article. But I think its basically wrong. Irony and humour are not synonyms and it would be a mistake to conflate the terms. Irony is a contrast between two things. By investigating the contrast in an “ironic” work of internet art you can figure out the argument behind it.

I don’t think netart “runs the risk of becoming … complacent” because it is definitely and intentionally already complacent. on purpose.

So a call to arms for netart to become more functionally political is a cool idea but whatever that art would be… it wouldn’t net art. but maybe it can be after net art.

@ Aurel

Thank you for your critique of the piece.

I agree with you, and do not subscribe to the idea that humor and irony are one in the same. I was not trying to make this point in my article.

I was attempting to state that humorous and more ironic content in Internet art is not necessarily a problem in itself. What is an issue is when this irony and humor overshadows or removes any political and social content from art. Some of the artists I described (such as RTmark, Electronic Disturbance theater, the Yes Men, and Nastio Mosquito) maintain a definite sense of humor (which occasionally involves irony) in their work. This sense of humor and irony never takes precedence over a social/political confrontation or effaces it entirely.

As you implied in your last sentence, I hope that more artists/producers will contemplate a more complex commitment to combining an address of social/political issues with humor and irony through artistic practice on the Internet and with new media.

Youre truly well informed and very intelligent.