|

|

|

|

|

|

The shadow of Francis Bacon looms large over London. He has been dead for twelve years now. Rarely can one find a piece of writing where his name is not mentioned along with the label “the most significant painter of the post-war era.” In 2001, The Daily Telegraph ran an article concerning the attempt of contemporary British artists to exorcise Bacon’s ghost from his favorite drinking spot: London’s exclusive Colony Room. An exhibition was held to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the club and featured the likes of Jane and Louise Wilson, Clash guitarist Paul Simenon, Pulp’s Anthony Glenn and, of course, Damien Hirst. The main goal was to create a new myth for the Colony Room. The new owner, Micahel Wojas wanted to keep it from being turned into a museum and replace the bohemian clichés so closely associated with Bacon: him and Lucian Freud huddling together to discuss the essence of being and dying in the modern age, while syphilitic aristocrats mingle and flirt with the pick-pockets and off-the-street drunks. Now, at the Colony Room, Damien Hirst can be seen serving drinks behind the bar as one of his spot paintings hangs in the background. Bacon is long gone and dead. In March 2003 his former lover and inheritor of his estate, John Edwards, passed away, leaving an estate worth millions of pounds in the hands of lawyers and gallery owners.

![]()

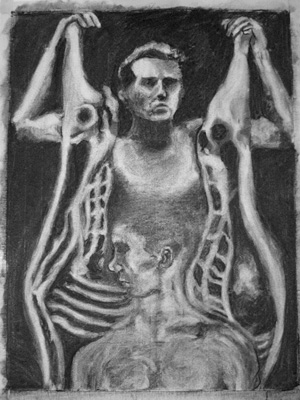

In the art world, the general guidelines for fame often adhere to the Oedipal

“kill the father” trajectory. Artists grow up admiring a particularly

potent artist: for many, it was Picasso, sometimes it is Velasquez, Rembrandt,

Cézanne, or even de Kooning. The artists spend their adolescence slavishly

copying their idol, and enter the art world with a shocking work, a pastiche

of their hero, which stylistically or conceptually pushes the boundaries of

modern art. They have broken free, the rest of their life is up to them to run

into the ground or elevate it to a level of being placed within a room inside

a museum alongside a mediocre work of their dead or aging idol. Bacon produced

the “Crucifiction of 1933,” ripping off Picasso. Hirst did the “Impossibility

of Death in the Mind of Someone Living” rendering Bacon in 3-D.

In the art world, the general guidelines for fame often adhere to the Oedipal

“kill the father” trajectory. Artists grow up admiring a particularly

potent artist: for many, it was Picasso, sometimes it is Velasquez, Rembrandt,

Cézanne, or even de Kooning. The artists spend their adolescence slavishly

copying their idol, and enter the art world with a shocking work, a pastiche

of their hero, which stylistically or conceptually pushes the boundaries of

modern art. They have broken free, the rest of their life is up to them to run

into the ground or elevate it to a level of being placed within a room inside

a museum alongside a mediocre work of their dead or aging idol. Bacon produced

the “Crucifiction of 1933,” ripping off Picasso. Hirst did the “Impossibility

of Death in the Mind of Someone Living” rendering Bacon in 3-D.

The art critic David Sylvester has been indispensable to Bacon’s myth. One of the most prolific champions of continental art, his Interviews with Francis Bacon, as well The Enigma of Francis Bacon, have provided the source material for numerous articles and many theses. From the countless pages Sylvester devoted to Bacon, a superhuman figure emerges: vital, decadent, drinking with his cronies at the local dive untill 4 a.m. only to return to his studio at 8:30 in the morning to work on the latest visionary piece, which, within a matter of three days, will be slashed up in a drunken rage—unless, of course, his dealer showed up dragging it away to sell for a substantial sum to the wealthiest collectors or museums.

The importance of a myth to the career of an artist can not be overemphasized. The work itself is rarely enough. Barthes’ idea that the author is dead is itself a myth. In museums, all of us look at the plates next to the artist’s work in an attempt to see beyond the canvas, the flatness of the projected piece or the manufactured dimensionality of sculpture or installation in order to get a glimpse of the soul of the person who created it for us. Sometimes the short paragraph offered to the viewer merely wets his or her appetite, and they go further. Libraries, book stores, on-line databases are torn apart in search of a single word of truth about the person who managed to capture our attention. The industry surrounding the manufacturing of an artist’s myth is great. We no longer believe in Ulysses, Agamemnon, John the Baptist, Joan of Arc or Napoleon. Yet, the hunger for heroes is still great. Of course, Hollywood and the music business offers plenty of idols, but they look a little too flat on the Late Show, and seem to smile too much for the cameras while extolling the virtue of anonymity and the latest diet craze in interviews. Some of them even have children, just to remind the public that they can procreate just like the others, and, besides, babies are cute and parenthood is still regarded with respect.

Very few people can name a single visual artist working today. In the last decade, Warhol, Pollock and Baquiat have been in the movies; Picasso’s life is still a source for great anecdotes and numerous biographies, while Vermeer and da Vinci continue to appease our mystical inclinations. Most of us need a good story: alcoholism, drug abuse, rough sex followed by moments of intense inspiration, when the world slows down and the artist can step outside of our common-day existence and capture its essence in fixed format.

Britain’s Damien Hirst is not squeaky clean, but no matter how hard he tries none of his transgressions matter in the U.S. In 2001 he was in the news for talking about the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in aesthetic terms. Last year, he exhibited a painting in New York, “Armageddon,” which presented the viewers a huge black surface covered with flies which smelled of death and decay. The show received positive reviews and was applauded for its existential profundity. America seems to like this sort of thing nowadays.

Francis Bacon was reportedly made by Kenneth Clark, then curator of London’s National Gallery, who came to his studio in the late ’40s and admired the painter’s work. In the late ’90s Damien Hirst met the exhibitions secretary at the Royal Academy of London naked at four o’clock in the afternoon sitting at the piano in Bacon’s Colony Room. Close to the end of his life Bacon actually saw one of Hirst’s fly pieces and reportedly spent an hour at the Saatchi gallery admiring it: “It kind of works,” he said in a letter to a friend, or at least that is what Hirst says.

Hirst’s On the Way to Work is his grandest attempt to feed on Bacon. David Sylvester’s Interviews with Francis Bacon was a canonical piece for neo-existentialist writers and painters. Created from a collection of interviews recorded in the period 1962-1986, the book shows Bacon undergoing a certain evolution and establishes him as a great interpreter of the symptoms of modern life. On the Way to Work contains interviews conducted from 1992 to 2001 and establishes Damien Hirst as the greatest interpreter of Bacon. It is sold as a “young student’s guide to making it as an artist.”

|

|

|

|

|

|