Reflecting on Haiti's Bicentennial |

Enzo Surin

|

On the eve of Haiti's 200th year Celebration of Independence, I sat on my parent's living room floor listening to my father talk about Haitian politics. Although our home is miles away from Haiti in the New York City borough of Queens, his face on that day was masked with urgent discontent as he began to outline the festivities planned for the momentous occasion. There was also a level of cynicism in his voice as he made his way closer to where I sat and reclined in a nearby chair.

Though he is usually tired after a day of work, that afternoon his energy was fueled by a passionate rant on ethnocentrism, racism, and the ability of Haitians to grow and prosper as a people. What would the New Year bring that past years had not brought?

"You know they plan on going to Haiti to celebrate our independence," he said. And before I could ask him who is planning on going to Haiti, he added with a note of laughter "But Haitians are wary. They might just take it from us." I laughed along with my father but soon realized that he was not fully joking. I know my father to be a conspiracy theorist, heck we all are at some level nowadays, but I wondered of there could be some truth to his paranoia.

Ten months later no one could have predicted the heartache and tremendous grief

that would strike Haiti as a result of epic floods. Thousands of people died

in the northern part of the country and many other bodies were not recovered.

In a state of extreme poverty, Haiti is once again trying to establish a functional

government.

So what's the celebration about? In order to understand what there might be to feel celebratory about, one must look at the history of the country. Death, poverty, and disease have never been new things to the people of Haiti and neither have the notions of perseverance and survival. Economic survival, more specifically, has remained a constant for a country that does not offer much to a developing global market.

Most of what I remember about growing up in Haiti consists of what I learned in school about General Jean-Jacques Dessalines and how he led to the establishment of Haiti as a republic on January 1, 1804. However, a significant number of events were experienced that would never find their way onto the pages of any textbook. As a young child growing up in the city of Petionville, I remember the violence and the civil unrest located only several miles outside the capital, Port-au-Prince. I was around seven or eight years old the days the protests and attacks started.

The Duvalier regime had been a black cloud reigning over the country for decades and the people were getting fed up. Both Franois and his son Baby Doc saw it fit to rule the country under a reign of terror, full of corruption, poverty, and murder. At the time, they changed the blue in the Haitian flag to black reflecting their dictatorship. Their secret police, known as the Tontons Macoutes, were not so secretive in their exploits of power over the people, a formula that would later cause the Haitian people to revolt against the government in an attempt to reclaim their freedom.

My father cautions "People are going to celebrate, but there is still shooting going on," and his skepticism is not without merit. Haiti's attempt to maintain civil order has been challenged over the past two decades just as much by ineffective leadership as power hungry, Duvalier-regime sympathizers. It is safe to say that any country led for years by a form of government other than democracy would need some time to make a successful transition.

Haiti has always been struggling with these types of issues but it has not been until recently that the world has started to take notice of the struggles of the Haitian people. The surge of Haitian culture to the forefront of American media, culture, and mainstream politics has occurred within the last ten to fifteen years.

The coup in the late eighties to oust then self-proclaimed president of Haiti, Baby Doc Duvalier, gave way to refugees entering nearby countries and the United States in astronomical numbers, not counting those who unfortunately perished en route. Then there was the AIDS scare in the early nineties and Haitian people being blamed for a rise in the disease in the United States because of their growing immigration numbers. The AIDS epidemic in this country was rising independent of Haitians and continues to do so today. Then there was the dreaded uprising by General Raoul C�dras, who wanted to take back the country after the people had elected Jean-Bertrand Aristide as president. He had to be removed from power by U.S.-led coalition forces, and Aristide was then returned to power.

On the surface, Haitians and Haitian-Americans did not have much to be proud of as the global media scrutinized certain things and overlooked others. Mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters were being lost to the violence and poverty. My family lost a cousin and a grandmother. It felt like Haiti was reverting back to the black clouds that once covered its beautiful mountain terrain. Then something changed.

More businesses and international aid started to pour into Haiti the same way it did for some other third-world countries. With the government being a little more stable, there was not the same fear that existed before and the perception of Haitians began to change. Political activists and leaders came forward and spoke on behalf of Haitians as a people and demanded the world to pay more attention to what was going on in the country. Wyclef Jean came along with his rap group the Fugees and he gave even more pride to the younger generation of Haitians and Haitian-Americans. Haiti was now on the world agenda. In a strange twist, it became cool to be Haitian; it was a trend. Pride was being reestablished.

The insurgence of Haitian culture into mainstream society did not necessarily mean it was welcomed to stay there this was highlighted by the sodomizing of a young Haitian named Abner Louima by New York City police officers. He was assaulted with a broom handle in his rectum and mouth while he was in police custody. Although he later sued the city of New York and won, it became evident that not all people welcomed the arrival of Haitians. Though the attack was not necessarily targeting a Haitian male, it left a harsh message in the minds of black America, but more specifically on Haitians already trying to shed some of their load.

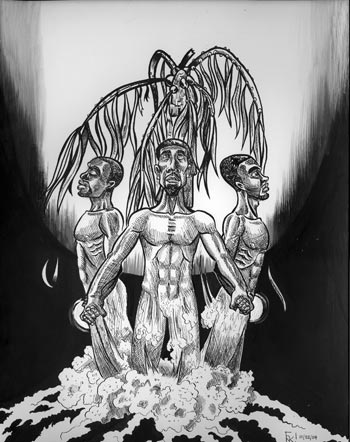

The years following this boom in Haitian culture wavered as much as any other trend. It is a reminder that pride in what you accomplish should not take a back seat to your current struggles. There is life to celebrate. There is honor and a love of country despite the hardships. I am proud of my upbringing and proud of the fervent spirit of a people who continually defy the odds. It is with this in mind that the bicentennial celebration of Haiti's independence came to fruition. There is an inscription on the Haitian flag that reads "L'union Fait La Force," it means "Unity in Strength." The relevance of that could not be more apparent.

December 2004