Slow Descent: The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon

How colonial influence and civil war left a nation divided.

By Elisabeth Lloyd Burkhalter

Elisabeth Lloyd Burkhalter is a first year in the MFAW program.

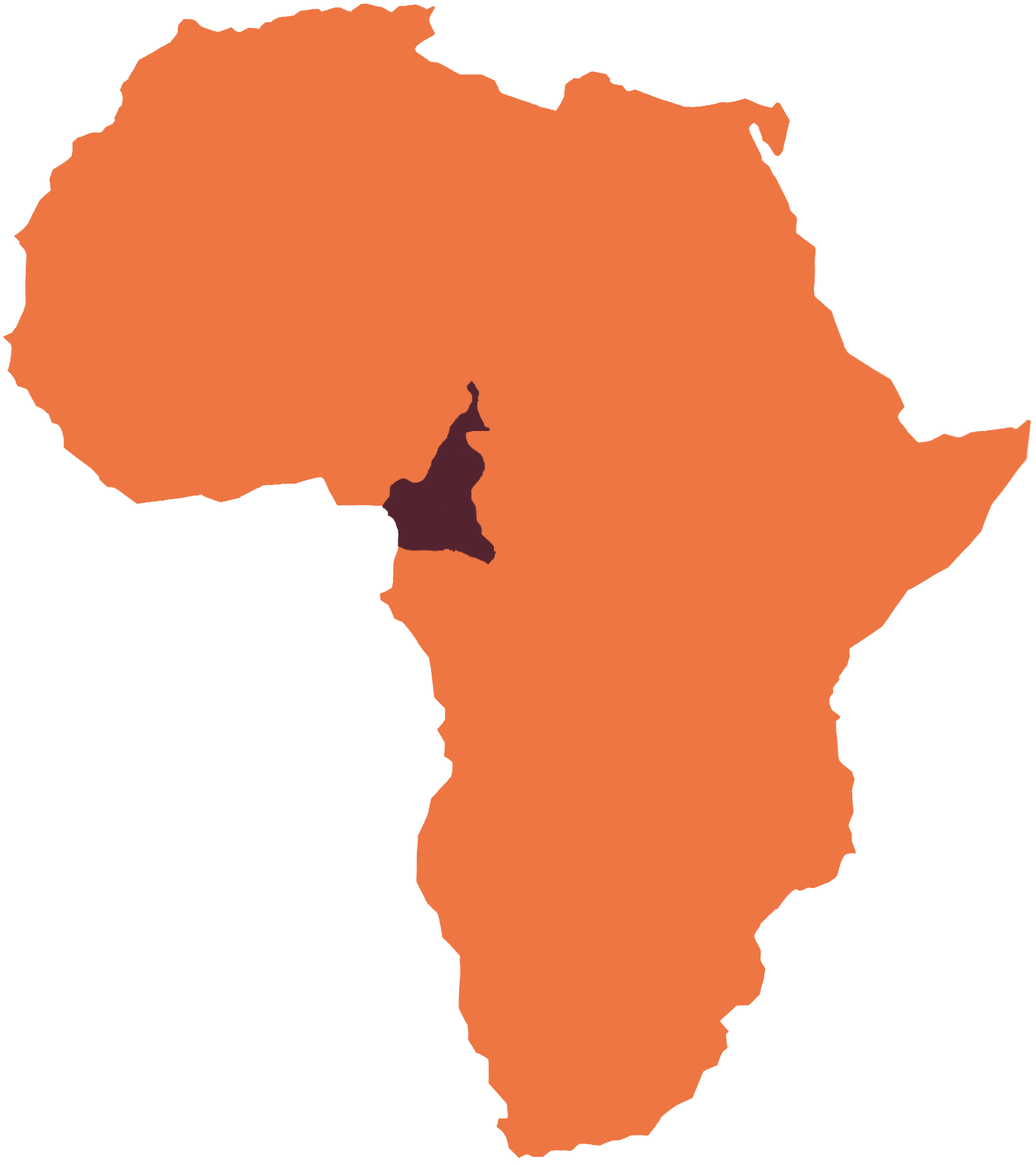

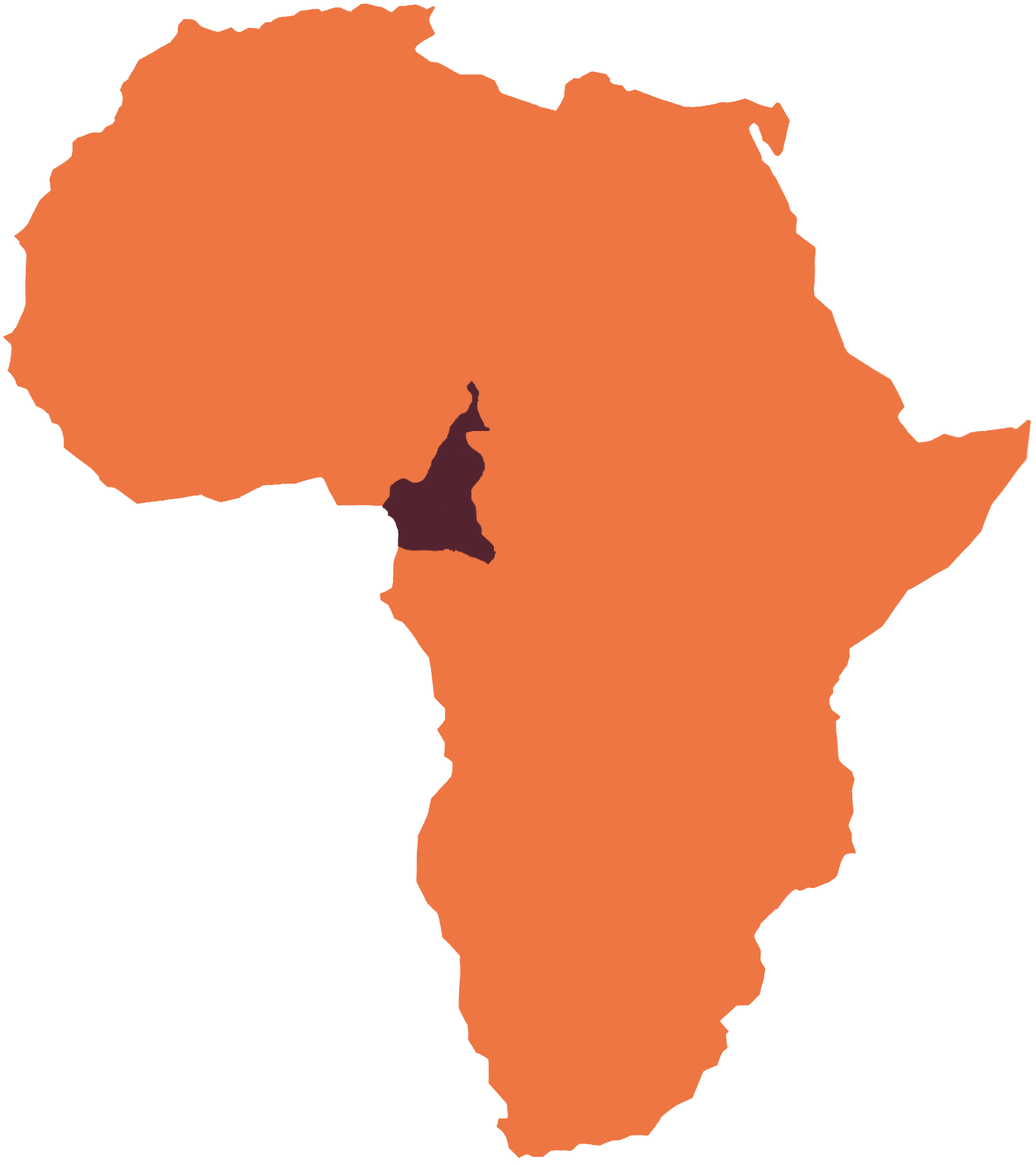

Maps by Elisabeth Lloyd Burkhalter

Illustration by Jade Sheng

We always flew into the port city, never the capital. Our flights from Paris landed at night and, the next morning, we would drive five hours inland to what was, for the time, home.

The port city, Douala, sits on the banks of the Wouri River, along which its inhabitants first came in contact with Europeans in 1472

On each trip, my partner and I stayed in the same hotel, a palmed oasis nestled in a shifty urban quarter. Built in cooperation with the Deustche Seemannsmission, it originated as a guest stop for sailors. Now, on any given night, the poolside restaurant provides a wide sampling of the expatriate community: the Chinese contractors rebuilding the country’s roads and laying pipelines, Italians who export timber, German N.G.O. workers, Americans in the Peace Corps and other such volunteers, and the French, of course. In a country where half of the currency reserves are kept in the French Treasury, we shouldn’t have been surprised to find our fellow countrymen everywhere.

From the Portuguese camarões, meaning shrimp, Cameroon’s name is a testament to Western arrival. Culturally and geographically, it is both West and Central African. Today, depending on whom you ask, the country goes by two names, though only one is internationally recognized.

Dubbed “Africa in Miniature,” its various landscapes contain every climate zone found on the continent.

Though its official languages are French and English — with two anglophone regions and eight francophone ones — Cameroon boasts incredible ethnic and linguistic diversity, with over 250 living languages. Despite rampant corruption, Cameroon’s trade partners (namely, China and France) and political allies in the fight against the Boko Haram insurgency in its far North region, including the U.S. and the U.K., have considered it a nation of relative peace and stability.

Like much of Africa, Cameroon’s borders are the arbitrary results of colonial and post-colonial decisions.

In November 2016, a string of events began to fissure that apparent peace. The government’s brutal crackdown on protests in the Anglophone city of Bamenda fueled a violent resistance, which escalated into an armed conflict between separatist Anglophone fighters and the (largely Francophone) Cameroonian government, engendering a large scale humanitarian crisis that has already seen half a million people internally displaced.

I was riding a communal taxi (i.e., essentially sitting on a fellow passenger) when I first heard about the strikes organized by Anglophone lawyers and teachers unions to protest centralization and Francophone domination. The radio blared warnings that the demonstrations, though nonviolent, could be an attempt to sunder “national unity” — a phrase I heard repeated in support of 87-year-old Paul Biya, the incumbent president since 1982 (making him the longest-ruling non-royal leader in the world). Agreement rippled through the taxi.

It was the first time I witnessed Francophone Cameroonians dismiss the grievances of their Anglophone compatriots. I had been in the country for less than a year, but I had intimations — by visiting Bamenda and working with an Anglophone at a women’s center — that the character of the country’s Anglo-Franco divide extended beyond linguistic differences.

The Anglophone demands seemed pretty reasonable, I announced. Wouldn’t they find it unjust to appear before a judge who spoke only English, for instance?

“Things are hard for us here, too,” the driver replied.

83 percent of the country’s population is Francophone.

By the following year, mass arrests of the more moderate activists had cleared a space for extremists to hijack the protests, forming various militant rebel groups and establishing the independent state of Ambazonia. The initial protests took place in Bamenda, the capital of the Northwest, and spread to other major cities in the Southwest. The central government in Yaoundé shut down the internet in both Anglophone regions for over a year, solidifying a sense of group identity and oppression among Anglophones, and President Biya declared war against the Ambazonia Defence Forces (ADF) and other “terrorists” in December 2017.

A number of abuses have been documented from both government security forces and the separatists groups. The Cameroonian military’s Rapid Intervention Brigade burned villages thought to house insurgents; the “Amba Boys” and other militant groups have enforced full municipal strikes known as “ghost towns” through intimidation of business owners and civil servants. Both sides have tortured and killed civilians — though the government’s body count far exceeds the separatists’. Schools in the Anglophone regions have been closed since November 2016, and Crisis Group estimates that the conflict has resulted in 35 thousand refugees in Nigeria, 440 thousand internally displaced persons (IDP), and 3,000 casualties thus far, as clashes between the government and separatist forces have intensified.

Some time after the initial protests and crackdowns, I spoke with a Francophone who had attended university in the Southwest Anglophone city of Buea. He described the division between Francophone and Anglophone students well before the events in 2016: If there were any sort of collaborative projects, for example, the groups would be entirely segregated. He said he tried to be a bridge, but it was impossible. No better barometer for the pressures of a country’s deep-seated resentments than in the attitude of its youths. But the Anglophone Crisis was born before their time, during the colonial era, whose legacy still looms large across the continent.

The 1961 “Reunification” of modern-day Cameroon saw a splitting up of the former British territories.

Like much of Africa, Cameroon’s borders are the arbitrary results of colonial and post-colonial decisions. After World War I, France and the United Kingdom jointly controlled the former German protectorate of Kamerun under League of Nations mandates. A year after the Francophone territory gained independence, the United Nations organized a plebiscite in the English-speaking territory with the choice between joining Nigeria or the newly established Republic of Cameroon. The third option, independence, was not listed.

Southern Cameroons (today the Northwest and Southwest regions of Cameroon) voted to unite with the Republic of Cameroon, while keeping a certain degree of autonomy. Under Cameroon’s first president, Ahmadou Ahidjo, who feared secession of the natural-resource-rich Southwest, a 1972 constitutional referendum consolidated executive power and abolished the nation’s federal system in favor of a unitary state.

Since then, the country’s Anglophone minority has complained of being treated as second-class citizens, excluded from top civil service jobs and marginalized by the appointment of non-English-speaking teachers and judges in their regions (some of whom are trained exclusively in French civil law, and not the British common law system used in the Anglophone regions). Compared to the Francophone regions they border, the Northwest and Southwest are underdeveloped in infrastructure.

In the 1990s, under current President Paul Biya, the police routinely disrupted attempts by Anglophone groups to restore the federation promised to their regions. (It is worth noting that separatist fighters refer to the Cameroonian government as “the colonizers in Yaoundé,” which could include both President Biya and the French government with whom he has close ties).

In short, it is the political economy of nation-building — the ability of the central government under both French-backed Presidents Ahidjo and Biya to garner elite support by redistributing rents — rather than any profound Cameroonian identity that has held the country together.

I recently spoke with a friend, A—, one of the few bilingual Cameroonians I met in the Francophone village of Bandjoun. His father is from Bambalang, a village in the Anglophone Northwest, and his mother is from outside of Bafoussam in the Francophone West. When I asked him about solidarity between Francophones and Anglophones, he said that Anglophone IDPs are generally well-received in Francophone regions, even as the influx of those fleeing violence has driven up unemployment and the cost of living in cities like Doula. “People know now the government is telling lies, the government is killing people.” A— also mentioned many of these Anglophone women are compelled to earn money by sex work. (For more on gender issues in militarized secessionist movements, see Jacqueline-Bethel Tchouta Mougoué’s "Gender, Separatist Politics, and Embodied Nationalism in Cameroon" 2019.)

As an online translator, A— has worked with Anglophones in the Southwest city of Buea (known as “Cameroon’s Silicon Valley”), who were devastated by the internet shutdown. He reports receiving threats because of his activity on social media, where he shares updates about the crisis. When I asked him about the dangers of circulating fake news online (a term used by African authoritative states to deny government involvement well before the Trump administration), A— said he waits a few days before sharing a video to avoid disseminating misinformation. He directed me to Mimi Mefo Info, a news platform started by award-winning Cameroonian journalist Mimi Mefo Takambou, which I recommend to anyone interested in reading about the conflict’s latest developments.

He said he tried to be a bridge, but it was impossible. No better barometer for the pressures of a country’s deep-seated resentments than the attitude of its youth.

A— and I had met during the prelude to the crisis, and although the Anglophone regions were close by, the conflict felt far away, not particularly urgent until it decidedly was. I was an outsider in Cameroon — there is a lot of history that I didn’t and still don’t completely grasp — and perhaps because of that, ever since I left, I have been trying to map out the country’s slow descent into civil war. Is it linear, an arch, a spiral?

For now at least, I’ve settled on it being something more like the experience of flying into a port at night — nothing but the ocean’s dark ripple, and suddenly a cluster of light, the city coalescing in luminescence — a protest movement after decades of suppression, spark in the powder keg, a village burned, followed by another and another, and, all at once, a country in flames. A crisis now deadlocked. Negotiations mediated by Switzerland in June of last year failed to produce significant results, and all but one faction of the Anglophone movement rejects this “Swiss Process.” With Ambazonian groups splintered by infighting, the Cameroonian government refusing to consider federation — and as the aging Biya faces mounting criticism after three years of fighting — what road leads to resolution?

Slow Descent: The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon

How colonial influence and civil war left a nation divided.

By Elisabeth Lloyd Burkhalter

Elisabeth (Lily) Lloyd Burkhalter is a first year in the MFAW program.

Maps by Elisabeth Lloyd Burkhalter

Illustration by Jade Sheng

We always flew into the port city, never the capital. Our flights from Paris landed at night and, the next morning, we would drive five hours inland to what was, for the time, home.

The port city, Douala, sits on the banks of the Wouri River, along which its inhabitants first came in contact with Europeans in 1472

On each trip, my partner and I stayed in the same hotel, a palmed oasis nestled in a shifty urban quarter. Built in cooperation with the Deustche Seemans Mission, it originated as a guest stop for sailors. Now, on any given night, the poolside restaurant provides a wide sampling of the expatriate community: the Chinese contractors rebuilding the country’s roads and laying pipelines, Italians who export timber, German N.G.O. workers, Americans in the Peace Corps and other such volunteers, and the French, of course. In a country where half of the currency reserves are kept in the French Treasury, we shouldn’t have been surprised to find our fellow countrymen everywhere.

From the Portuguese camarões, meaning shrimp, Cameroon’s name is a testament to Western arrival. Culturally and geographically, it is both West and Central African. Today, depending on whom you ask, the country goes by two names, though only one is internationally recognized.

Dubbed “Africa in Miniature,” its various landscapes contain every climate zone found on the continent.

Though its official languages are French and English — with two anglophone regions and eight francophone ones — Cameroon boasts incredible ethnic and linguistic diversity, with over 250 living languages. Despite rampant corruption, Cameroon’s trade partners (namely, China and France) and political allies in the fight against the Boko Haram insurgency in its far North region, including the U.S. and the U.K., have considered it a nation of relative peace and stability.

Like much of Africa, Cameroon’s borders are the arbitrary results of colonial and post-colonial decisions.

In November 2016, a string of events began to fissure that apparent peace. The government’s brutal crackdown on protests in the Anglophone city of Bamenda fueled a violent resistance, which escalated into an armed conflict between separatist Anglophone fighters and the (largely Francophone) Cameroonian government, engendering a large scale humanitarian crisis that has already seen half a million people internally displaced.

83 percent of the country’s population is Francophone

I was riding a communal taxi (i.e., essentially sitting on a fellow passenger) when I first heard about the strikes organized by Anglophone lawyers and teachers unions to protest centralization and Francophone domination. The radio blared warnings that the demonstrations, though nonviolent, could be an attempt to sunder “national unity” — a phrase I heard repeated in support of 87-year-old Paul Biya, the incumbent president since 1982 (making him the longest-ruling non-royal leader in the world). Agreement rippled through the taxi.

It was the first time I witnessed Francophone Cameroonians dismiss the grievances of their Anglophone compatriots. I had been in the country for less than a year, but I had intimations — by visiting Bamenda and working with an Anglophone at a women’s center — that the character of the country’s Anglo-Franco divide extended beyond linguistic differences.

The Anglophone demands seemed pretty reasonable, I announced. Wouldn’t they find it unjust to appear before a judge who spoke only English, for instance?

“Things are hard for us here, too,” the driver replied.

It was the first time I witnessed Francophone Cameroonians dismiss the grievances of their Anglophone compatriots. I had been in the country for less than a year, but I had intimations — by visiting Bamenda and working with an Anglophone at a women’s center — that the character of the country’s Anglo-Franco divide extended beyond linguistic differences.

The Anglophone demands seemed pretty reasonable, I announced. Wouldn’t they find it unjust to appear before a judge who spoke only English, for instance?

“Things are hard for us here, too,” the driver replied.

By the following year, mass arrests of the more moderate activists had cleared a space for extremists to hijack the protests, forming various militant rebel groups and establishing the independent state of Ambazonia. The initial protests took place in Bamenda, the capital of the Northwest, and spread to other major cities in the Southwest. The central government in Yaoundé shut down the internet in both Anglophone regions for over a year, solidifying a sense of group identity and oppression among Anglophones, and President Biya declared war against the Ambazonia Defence Forces (ADF) and other “terrorists” in December 2017.

A number of abuses have been documented from both government security forces and the separatists groups. The Cameroonian military’s Rapid Intervention Brigade burned villages thought to house insurgents; the “Amba Boys” and other militant groups have enforced full municipal strikes known as “ghost towns” through intimidation of business owners and civil servants. Both sides have tortured and killed civilians — though the government’s body count far exceeds the separatists’. Schools in the Anglophone regions have been closed since November 2016, and Crisis Group estimates that the conflict has resulted in 35 thousand refugees in Nigeria, 440 thousand internally displaced persons (IDP), and 3,000 casualties thus far, as clashes between the government and separatist forces have intensified.

Some time after the initial protests and crackdowns, I spoke with a Francophone who had attended university in the Southwest Anglophone city of Buea. He described the division between Francophone and Anglophone students well before the events in 2016: If there were any sort of collaborative projects, for example, the groups would be entirely segregated. He said he tried to be a bridge, but it was impossible. No better barometer for the pressures of a country’s deep-seated resentments than in the attitude of its youths. But the Anglophone Crisis was born before their time, during the colonial era whose legacy still looms large across the continent.

The 1961 “Reunification” of modern-day Cameroon saw a splitting up of the former British territories.

Like much of Africa, Cameroon’s borders are the arbitrary results of colonial and post-colonial decisions. After World War I, France and the United Kingdom jointly controlled the former German protectorate of Kamerun under League of Nations mandates. A year after the Francophone territory gained independence, the United Nations organized a plebiscite in the English-speaking territory with the choice between joining Nigeria or the newly established Republic of Cameroon. The third option, independence, was not listed.

Southern Cameroons (today the Northwest and Southwest regions of Cameroon) voted to unite with the Republic of Cameroon, while keeping a certain degree of autonomy. Under Cameroon’s first president, Ahmadou Ahidjo, who feared secession of the natural-resource-rich Southwest, a 1972 constitutional referendum consolidated executive power and abolished the nation’s federal system in favor of a unitary state.

Since then, the country’s Anglophone minority has complained of being treated as second-class citizens, excluded from top civil service jobs and marginalized by the appointment of non English-speaking teachers and judges in their regions (some of whom are trained exclusively in French civil law, and not the British common law system used in the Anglophone regions). Compared to the Francophone regions they border, the Northwest and Southwest are underdeveloped in infrastructure.

In the 1990s, under current President Paul Biya, the police routinely disrupted attempts by Anglophone groups to restore the federation promised to their regions. (It is worth noting that separatist fighters refer to the Cameroonian government as “the colonizers in Yaoundé,” which could include both President Biya and the French government with whom he has close ties.)

In short, it is the political economy of nation-building—the ability of the central government under both French-backed Presidents Ahidjo and Biya to garner elite support by redistributing rents—rather than any profound Cameroonian identity that has held the country together.

He said he tried to be a bridge, but it was impossible. No better barometer for the pressures of a country’s deep-seated resentments than in the attitude of its youths.

I recently spoke with a friend, A—, one of the few bilingual Cameroonians I met in the Francophone village of Bandjoun. His father is from Bambalang, a village in the Anglophone Northwest, and his mother is from outside of Bafoussam in the Francophone West. When I asked him about solidarity between Francophones and Anglophones, he said that Anglophone IDPs are generally well-received in Francophone regions, even as the influx of those fleeing violence has driven up unemployment and the cost of living in cities like Doula. “People know now the government is telling lies, the government is killing people.” A— also mentioned many of these Anglophone women are compelled to earn money by sex work. (For more on gender issues in militarized secessionist movements, see Jacqueline-Bethel Tchouta Mougoué’s "Gender, Separatist Politics, and Embodied Nationalism in Cameroon" 2019.)

As an online translator, A— has worked with Anglophones in the Southwest city of Buea (known as “Cameroon’s Silicon Valley”), who were devastated by the internet shutdown. He reports receiving threats because of his activity on social media, where he shares updates about the crisis. When I asked him about the dangers of circulating fake news online (a term used by African authoritative states to deny government involvement well before the Trump administration), A— said he waits a few days before sharing a video to avoid disseminating misinformation. He directed me to Mimi Mefo Info, a news platform started by award-winning Cameroonian journalist Mimi Mefo Takambou, which I recommend to anyone interested in reading about the conflict’s latest developments.

As an online translator, A— has worked with Anglophones in the Southwest city of Buea (known as “Cameroon’s Silicon Valley”), who were devastated by the internet shutdown. He reports receiving threats because of his activity on social media, where he shares updates about the crisis. When I asked him about the dangers of circulating fake news online (a term used by African authoritative states to deny government involvement well before the Trump administration), A— said he waits a few days before sharing a video to avoid disseminating misinformation. He directed me to Mimi Mefo Info, a news platform started by award-winning Cameroonian journalist Mimi Mefo Takambou, which I recommend to anyone interested in reading about the conflict’s latest developments.

A— and I had met during the prelude to the crisis, and although the Anglophone regions were close by, the conflict felt far away, not particularly urgent until it decidedly was. I was an outsider in Cameroon — there is a lot of history that I didn’t and still don’t completely grasp — and perhaps because of that, ever since I left, I have been trying to map out the country’s slow descent into civil war. Is it linear, an arch, a spiral?

For now at least, I’ve settled on it being something more like the experience of flying into a port at night — nothing but the ocean’s dark ripple, and suddenly a cluster of light, the city coalescing in luminescence — a protest movement after decades of suppression, spark in the powder keg, a village burned, followed by another and another, and, all at once, a country in flames. A crisis now deadlocked. Negotiations mediated by Switzerland in June of last year failed to produce significant results, and all but one faction of the Anglophone movement reject this “Swiss Process.” With Ambazonian groups splintered by infighting, the Cameroonian government refusing to consider federation — and as the aging Biya faces mounting criticism after three years of fighting — what road leads to resolution?