Rose Hellesen dressed in her fursuit of Silk and pointing at the poster and announcement wall on the 4th floor of the Sharp Building. Picture taken by Sisel Gelman.

Ready for more curiosity-quenching information on furries? Welcome back to “Slut Saga’s” collaboration with Rose Hellesen, an autistic furry.

In this final episode of the two-part series, we are excited to expand on the topics introduced in Part 1 and to talk more about the queer nature of the fursuit and the liberating experience of fursuiting.

…

The fursuit is one of the defining practices of the furry fandom. It is, as mentioned in Part 1, a safe space for furries to celebrate their personality, gender identity, and more.

But how did the tradition of the fursuit all start?

Hilda the Bambioid

In the early 1980s, most furry content was shared through amateur press associations which published compilations of furry art, comics, and writing to a small subscriber base, with one of the most well known subscriptions being Vootie, the APA which hosted Omaha the Cat Dancer. Back then, the main outlet of artistic expression — and what defined the fandom to outsiders — was its visual art (drawings or paintings).

The rise of costuming in the furry fandom is the evolution of skills and resources that took the fandom from a 2-D space into its vibrant modern 3-D form. People challenged themselves to innovate how they brought their fursonas to life, and now fursuits have become the dominant image that people think of when discussing furries.

Fursuits are the most tactile way a person can experience their fursona as a concrete version of themselves, rather than just an artistic extension.

The concept of the fursuit emerged, like the fandom itself, out of sci-fi cosplay culture in the early ’80s. As we discussed in Part 1, the furry fandom first began as an offshoot of the sci-fi genre, and before the first convention in 1989 prominent members of the fandom like Mark Merlino often held meetups, known as “furry parties” inside their hotel rooms at sci-fi conventions.

These cons had an established culture of cosplay, and so as the furry fandom grew into filling its niche, certain concepts were borrowed from the larger cosplay community. However, the creation of the first fursuit can be pinpointed to one man, Robert Hill.

Hill, a cartoonist and professional Disney character costumer, made the first fursuit in 1988: a sexy dominatrix “Bambioid” named Hilda. (A Bambioid is a type of matriarchal alien deer created by furry artist Jerry Collins).

Hilda’s costume is a deer character-head with a skin-tight, black, strappy one-piece suit and thigh-high boots. He sculpted Hilda’s head out of clay, “made a mold and fiber-glassed it,” and then sewed the rest of the costume together.

Because of her design and the way Hill moved in the costume, most people thought it was a woman who was playing Hilda. In a way, Hilda is an example of what can be considered a cross between fursuiting and drag.

One way to define drag is by the performance of exaggerated gender for entertainment or societal criticism. Drag queens (usually, but not always, men) will crossdress as women under a persona and perform a routine that can include comedy or satire among other forms of entertainment.

Hilda fits this definition of drag as Hill, a man, would dress up as a hyper-feminine anthropomorphic femme deer to be entertaining and satirical at ConFurence Zero in 1989. In a way, one of the only differences between Hilda and other drag queen personas is that one is an anthropomorphic deer and the other is a human character.

It might be a coincidence or just a visible shift in the culture of the time, but the creation of Hilda the Bambioid coincided with the mainstream’s “discovery” of Ball Culture in 1990. Ball Culture —an underground LGBTQ+ subculture — developed in New York City’s Black, Latinx, and queer communities as a form of expression through performance and a way to comment on and satirize topics of gender and wealth. Ball Culture had been a relatively insular community until the documentary “Paris is Burning,” and Madonna’s “Vogue” music video, brought it to the attention of white, straight culture.

Of course, “Paris is Burning” and Madonna’s music video should not be the sole way to learn about Ball Culture, and we urge “Slut Saga” readers to diversify their sources on the topic.

Drag was a key aspect of Ball Culture. The overlap between Hilda, Ball Culture, and drag implies that the 1990s were a time in which queer people were questioning the preconceived notions of gender, and challenging its perceived binary expressions.

The Furry Fandom was as much a pioneer of queer thought and gender expression as non-furry spaces were (like those found in Ball Culture in New York City).

And while not every fursuit today is related to drag, the radical self-expression that Robert Hill created in Hilda is still alive and well in fursuiting. Drag-like hyper-femme fursuits still exist in the fandom today, as seen in characters like Fiona Maray and masculine types such as those made by Mixed Candy.

Furries and the Fursuit

So, why wear a fursuit? Well, it’s one of the most visible aspects of the community (for good reason) and while it is one thing to enjoy and consume furry media, the fursuit is often seen (both within the community and outside of it) as the “final form” of a furry.

And to fully articulate why, Rose is going to switch into first person:

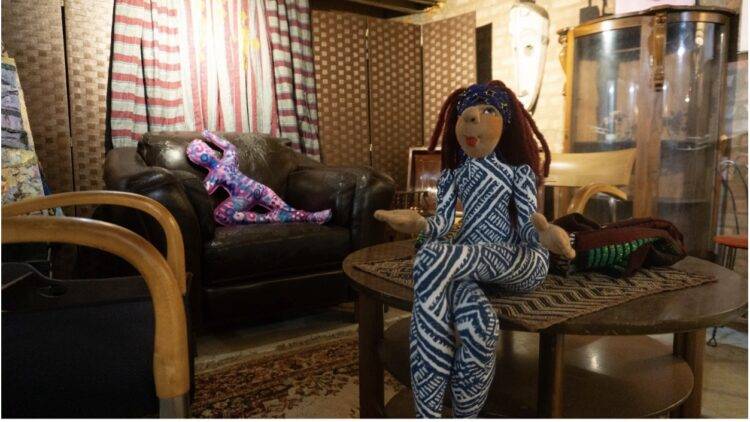

Hello, it’s me, the skulldog you’ve seen on the cover of this article! While I could speak in universals, many aspects of fursuiting are deeply personal to my own experience.

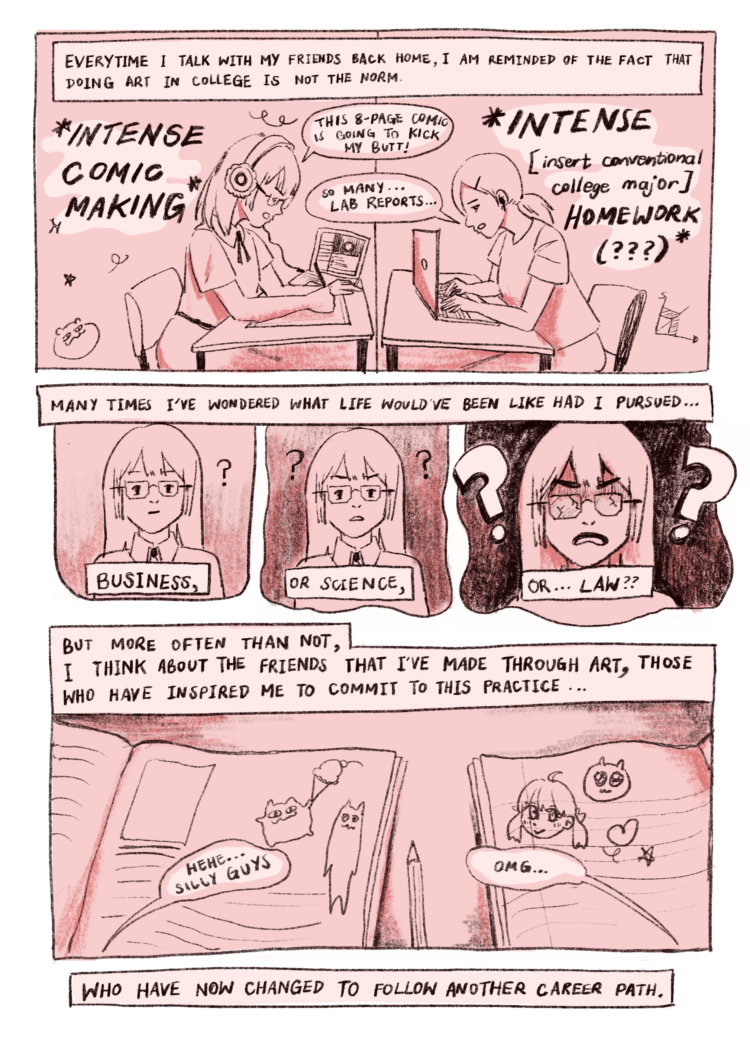

Why do furries fursuit? A different reason exists for each person. Here’s mine: This may be a shock, but I didn’t come into this world knowing I would dress up as a porcelain-faced skull creature. However, I did come into this world autistic. My experience of this world has always been atypical, and this was no different than when it came to perceiving my own self.

The relation I’ve had to my body, and specifically my face, has been largely just one of identification; the most my face and I talk to each other is when I look in the mirror and go “Yep, that’s me.” It’s less of a homogeny and more of a tolerance. I always accepted that this discontinuity would be perpetual.

I tried cosplay in my early teens, but it never really felt right for me. The main problem I had was that at the end of the day, no matter how accurate my clothing was, my face was still my face. I felt mismatched in the impression I had of myself to how I knew other people would look at me. I knew who I was, but all people knew was what I looked like.

I had always had a passive interest in the furry fandom, mainly just because of how cute all the characters were. But as I became more discontent with the limitations cosplay had in expressing myself, I realized that there was something intoxicatingly appealing in the idea of a fursuit — the notion that I could completely encase myself in a new outer image that could be anything at all I wanted seemingly solved every problem I had with my self-perception.

I realized that I really, really, really wanted a fursuit.

And so, like anybody else during the COVID-19 pandemic, I spent the early months of 2021 online, specifically stalking the dealer’s den, a fursuit-buying website. I had some money from the stimulus check (remember those?), and I landed on a fennec fox!

This fursuit partial —meaning it only has a head, paws, and tail— was being sold by a newer maker for $650, which is much cheaper than most fursuit partials (they typically sell for $1500 – $3000). I told my mom, whose only concern was that if I’d use the suit enough, that I wanted to buy it, and she agreed. I named my brand new fursona “Mabel“, and when I first put on the suit I was absolutely ecstatic.

Mabel was cute. I, for the first time, was cute. People told me I was cute! I wore her every once in a while, mainly for Halloween or for photoshoots — this was back in 2021 — so I didn’t have any conventions to go to.

Jumping to 2022, Al from Part 1 of this series, expressed interest in having a fursuit for himself since he had seen how emotionally freeing it was for me to completely assume a new identity. We chatted for a while about what species this new character could be, and eventually, we settled on a “skulldog,” the fandom name for a skull-faced canine.

As a trans-masculine man, he was especially drawn into the concept of creating a masculine fursona for himself. He wanted to lean into a refined, princely character, and a skulldog fit perfectly with the aesthetic. After countless revisions, we realized that a porcelain-style skull would articulate exactly what we wanted for the character, and figured if we were already going through the effort of making one, why not make two?

Thus, the twin skulldogs Silk and Velvet were born, and just in time for the both of us to go to our first furry convention: Anthrocon 2023! While I had worn Mabel here and there, this was our first time going fursuiting in a furry-specific venue.

Somehow, “life-changing” is still an understatement. For the four days of the convention, both Al and I wore our fursuits almost the entire time. It was honestly the first time I’ve ever felt completely, totally happy to be looked at. Almost constantly people were asking for our photos, telling us we were beautiful, and just supporting us expressing ourselves.

There were over 13,000 attendees. Typically, because I’m autistic, I get overwhelmed in crowds after about half an hour, and even when I push through because I want to enjoy an event I come back absolutely drained, if not completely nonverbal. But fursuiting took away every single aspect of socialization that drains me since the fursuit acts as a physical barrier between me and the world.

Every sensory impression gets reduced in a fursuit: my vision is dimmed, about as much as the tint of sunglasses, my hands are covered in fur and bury any sense of touch, and all the sounds around me are dampened within a fursuit head. It’s also common for fursuiters to be what’s called a silent suiter, or a fursuiter that chooses not to talk, this is what both Al and I elected to do throughout our time at the convention.

With all these factors together, I was able to experience a convention exactly how I wanted to. I still was able to socialize the entire time, but all the fear of being seen, all the overwhelming sounds of a public space, everything that made it so difficult for me, all of it was solved by a fursuit. There was continuity of how I felt within myself, and the image I projected to the world. I could finally interact with other people willingly and happily. The furry fandom created a space for me to represent myself and supported me as I showed off a true, genuine version of me.

Rose Hellesen dressed in her fursuit of Silk sitting in the Sharp Building cafeteria. Photo by Sisel Gelman

Why do we do this? Well, every backstory is different, but I can confidently say that all fursuiters are united in the euphoric experience of representing themselves in a way beyond fashion or makeup. To be completely concealed in a fursuit creates a blank canvas for anything: any species, gender, fashion sense, etc. This complete reinvention of the self allows you to articulate exactly how you truly want to be perceived by others in a way wholly unlike any other.

To put it simply: we fursuit because we want to show the world who we actually are.

So… Why are Furries Considered Cringe?

Unsurprisingly, ableism.

According to health and science reporter Sarah Boden from 90.5 WESA, about 15% of Furries also identify as neurodivergent. Many of the traits that are associated with Furries — such as hyperfixations and an extreme special interest in their fursona — stem originally from the Autistic community.

In Rose’s experience when furries meet each other, there is a visible excitement that is seen as impermissible by neurotypical standards. Actions such as jumping up and down or excitedly hugging are seen as too much by neurotypical standards because they do not fit into the mold of what is socially acceptable. The way the neurotypical system of oppression works is through intimidation and conformity.

Neurotypical culture rejects and punishes neurodivergent behaviors by making them seem “cringey.” By making these behaviors “uncool” and assigning a negative value to them, neurotypical people have the societal green light to ostracize and ridicule people who present these traits.

Therefore, the usage of exclusionary practices is weaponized to marginalize multiple communities at once: both furries and neurodivergent people.

Dominant culture wants people to believe that furries (and by extension, autistic people and the neurodivergent community) are cringe and that this non-permissible cringe is natural, eternal, and truthful to the furry concept.

It is not. There is nothing intrinsically cringey about being a furry. It is society’s framework that makes it seem like it is.

It is important to recognize the exclusion of furries in society as a systemic problem interwoven with other problems surrounding oppressive systems of power.

To Conclude

The world of the furry fandom is a misunderstood space of love, freedom, and authenticity.

We hope that through this two-part series, “Slut Saga” readers have become more educated on the nature of furries, the community’s history, and its appeal.

The furry fandom, most of all, allows its members to be liberated from societal expectations of gender and sexuality. The sex-positive, queer-friendly nature of the fandom allows it to thrive in ways unlike any other fandom space. While a love of anthropomorphic design is still at the core of the fandom, this design is used not just as an object of appreciation, but as a means of true, authentic, expression.

Read More →