There are so many of us whose first language isn’t English. We have such a unique relationship with English. As some friends and I got to talking over the last year, we realized just how much power the language has, as social capital in our countries. It also has power on individual levels, where the sheer exhaustion of having to translate your thoughts all the time is a very real thing.

This series is an exploration of everything that happens in the act of translation. How it happens in your head, how it affects you, what words are so hard to translate, what emotions you can only access in your own language. The best part is that this is a bilingual series. It looks like whatever language the writer is thinking in, to give you, our readers, an idea of what the inside of this everyday translation process looks like.

— Darshita Jain

Lit Editor

Calaveritas and the Day of the Dead

by Luis López

Nov. 2, the Day of the Dead in Mexico, is my favorite holiday for so many reasons. It is the time to remember our loved ones who have passed on; to create elaborate altars filled with their pictures and favorite foods and drinks, filled with marigold petals that in traditional beliefs guide the spirits’ way back to the realm of the living for one night a year. It is also the ideal time to indulge in some pan de muerto and hot chocolate. And apart from all that, it’s the one time that I can read poetry in the newspaper.

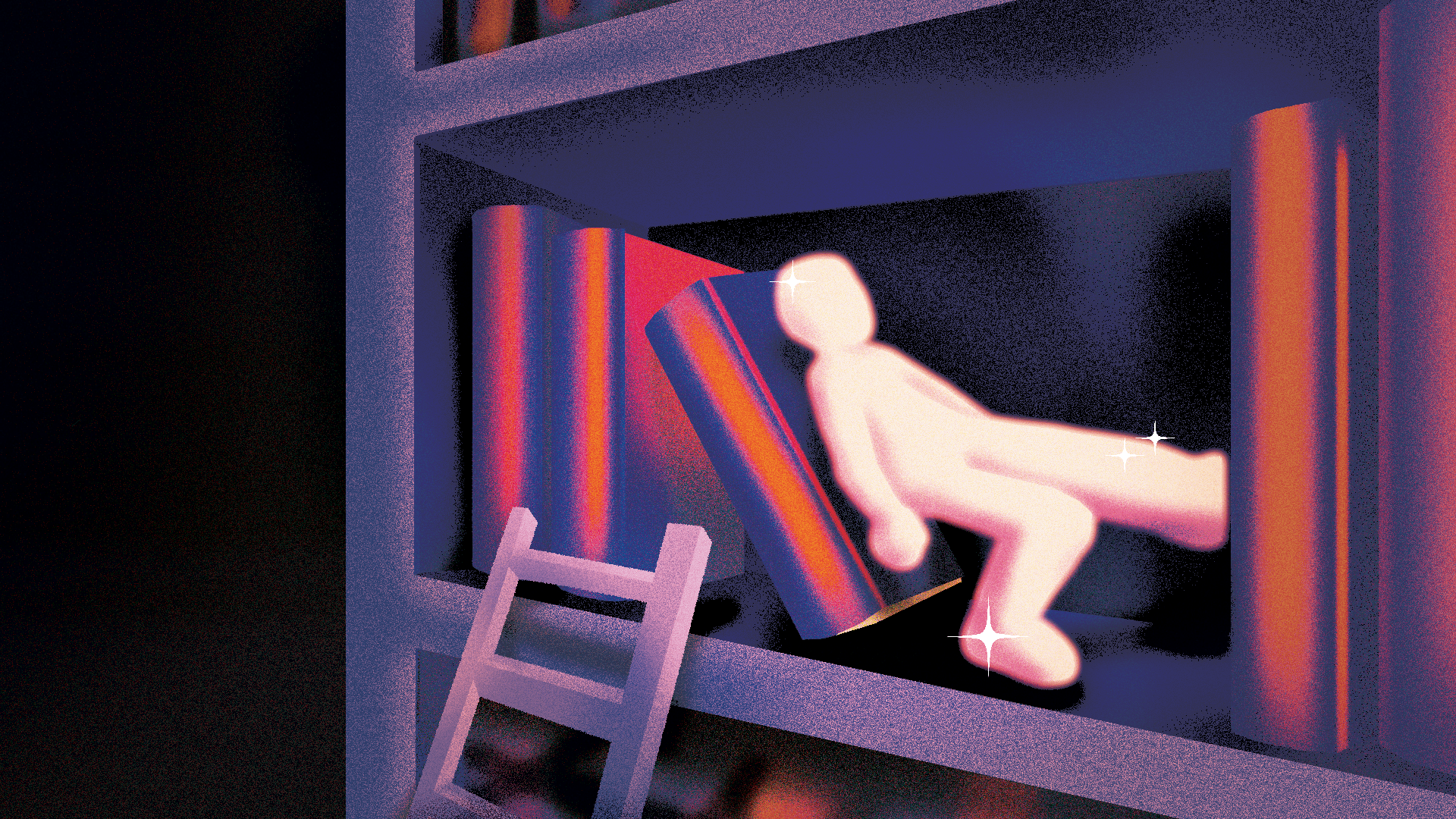

On that day, a spread features dozens of calaveritas, short poems that serve as affectionate accounts of someone’s death. Politicians, celebrities, and religious authority figures — all living — will each have one or two stanzas dedicated to them about when and how Death found them, accompanied by a toothy skull cartoon drawing of each person. The poems are meant to be playful and satirical — an ideal opportunity to take a jab at a major scandal in a zeitgeisty way.

Newspapers, of course, are not the only place where calaveritas appear, only the most public one. But a person with a knack for quick rhymes can write a few for their family or close friends. The tradition summarizes the essence of the Day of the Dead: a belief, deeply ingrained in Mexican culture, that death doesn’t have to be just a sad, heavy subject.

Neither the calaveritas nor the Day of the Dead in general mock or minimize grief. Rather, they offer a day in the year where mourning a loved one’s loss can be put aside to celebrate their life and the chance to spiritually connect with them. People will crowd the cemeteries, laying flowers on their family graves and spending time together there. People will have lunch there, dedicate songs to their passed relatives — full mariachis are often hired to perform in graveyards that day — or simply talk to their deceased, filling them in on what’s new since last year.

Good calaveritas can make many people laugh, but the best ones make the subject chuckle. In the end, the goal is to make them smile after reading about their own ultimate demise when Death ideally arrives while they’re doing what they love the most. In essence, it’s about celebrating the possibility of someone living their best life until their literal last breath. If we’re all going there, why not entertain the idea and laugh while we’re at it?

The rules for a good calaverita are simple but must be followed closely in order to compose an effective one. Verses are traditionally eight syllables long to give them a sing-songy feel. They must also have a defined rhyme scheme (usually ABAB or ABBA) that must be consistent throughout. Finally (and perhaps obviously), it has to be about death. Although they are usually in Spanish, I decided to try out a few bilingual examples jumping from one language to another as I make fun of a few people who might not be as larger than life as we think they are.

Bernie Sanders

Ya se andaba petateando

Después de aquel patatús.

But ol’ Bernie’s still peleando

Making headlines on the news.

La Muerte lo vio en la tele,

And she thought “¡ay, madre mía!

¿Qué le queda a este pelele?

¿One percent de batería?”

Natalie Wynn

Grabando un video nuevo

Under glaring, hot pink light

Natalie looked pretty fuego

In La Muerte’s deathly sight.

Natalie, al ver a La Flaca

Le dijo “Hey, how are you?”

Death firmly gripped an estaca,

“Goodbye, Diosa de YouTube!”

Lizzo

Lizzo poured herself a hearty

Shot de tequilita fuerte.

Who was also at that party?

One hundred percent La Muerte!

Not long after, la bebida

Tumbó a la super chanteuse,

Y La Muerte, complacida,

Dijo “blame it on the juice!”

Lin-Manuel Miranda

Overlooking el Caribe

Boricua, from his veranda

La Muerte creyó imposible

Resistirse al buen Miranda

“I’m a fan,” le dijo aquella,

“Pero eso won’t make me stop.

Lástima, I have to slay ya.

I’m not throwin’ away my shot!”