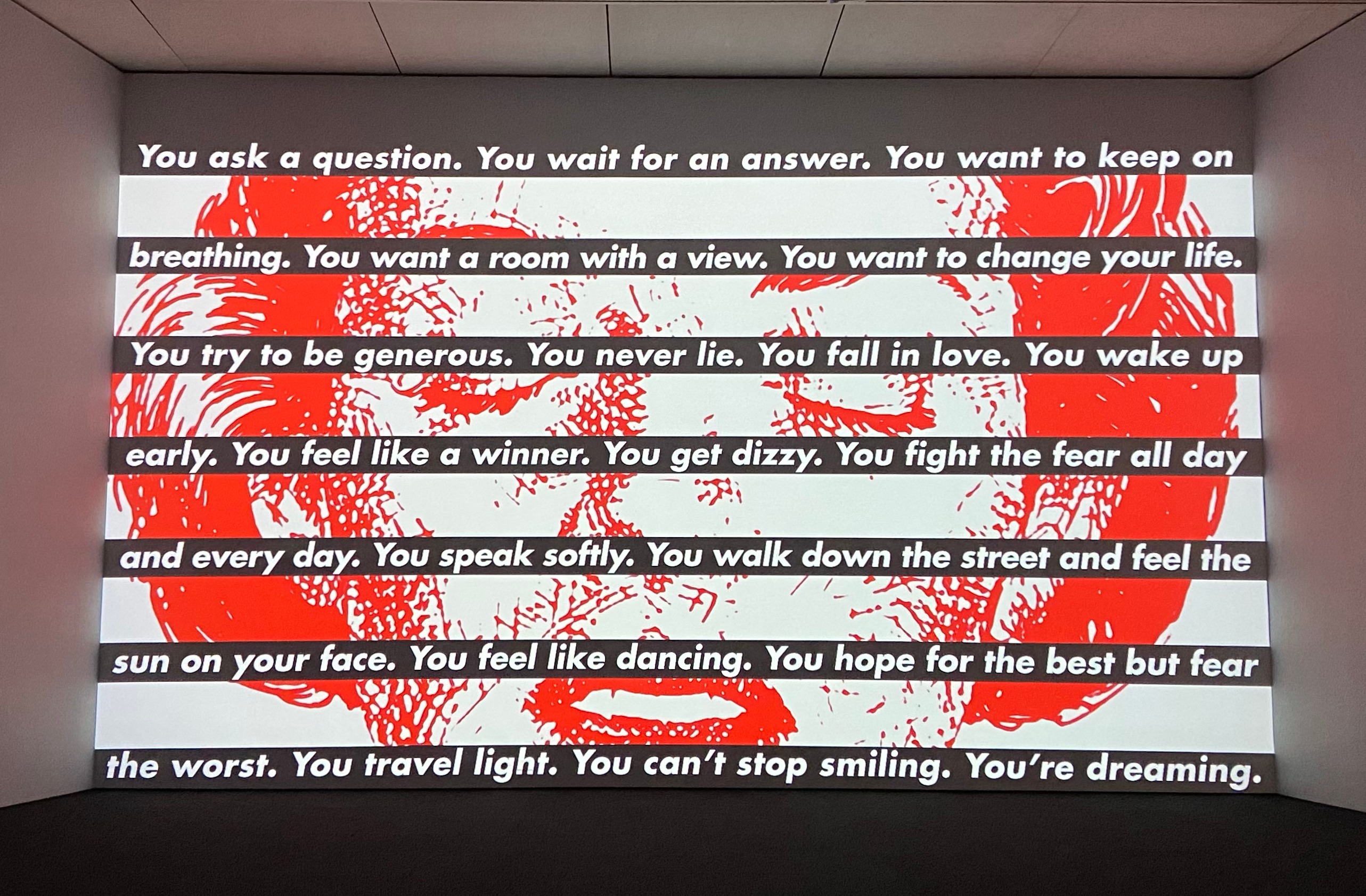

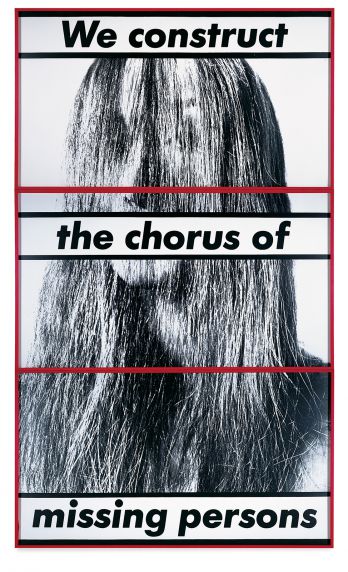

Barbara Kruger

“Untitled (We construct the chorus of missing persons),” 1983

Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, restricted gift of Paul and Camille Oliver-Hoffmann, 1984.22.ac

Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago

The titles for art exhibits are usually inept at unfolding the crux of object arrangements that a gallery might be showcasing at any given time. In other words, title hardly ever dictates or fully describes the content. “Color Bind” at the Museum of Contemporary Art is a different beast in this regard, both for the brevity of the two-word title used to describe an entire show about works that are either black, white or both, but also in what it’s not telling us through the omission of the consonant “L.” One might feel they’re experiencing color blindness while navigating the 54+ piece monochromatic exhibition.

While mounting “Color Bind,” curator Naomi Beckwith not only chose completely black and white work, but also she removed any trace of didactic textual explanations. “I really wanted to try to engender this kind of basic entry point: It’s black or it’s white — and then let the question come afterwards — What is it doing?” Beckwith said in an interview with F Newsmagazine. In this exhibition, she prefers to let the viewers assemble their own narrative discourses through exploration. Thematic fodder includes life, death, sex and race. Of course, everything else is open for interpretation.

Barbara Kruger’s “Untitled (We construct the chorus of the missing persons)” (1983), a portrait of an unidentifiable individual obscured by bands of text, raises questions such as: does the “We” refer to collective consciousness, or an ambiguous “we” that the depicted person tells us to be wary of? Does the individual even belong to the same group of “we” as the viewer or are they part of the “chorus of missing persons?” And what exactly is a “chorus of missing persons?” Kruger creates a mystery that will hopefully partially resolve itself within viewers via their historical experiences and political individuality, a theme of “constructing a discourse” that is consistent throughout the exhibition.

“Naturally, as the project progresses, you begin to move towards all sorts of metaphoric meanings of what black and white can be,” Beckwith explained. “The question becomes: how can an exhibit navigate from this question of the monochrome to something that feels more conceptual, theoretical and metaphorical?”

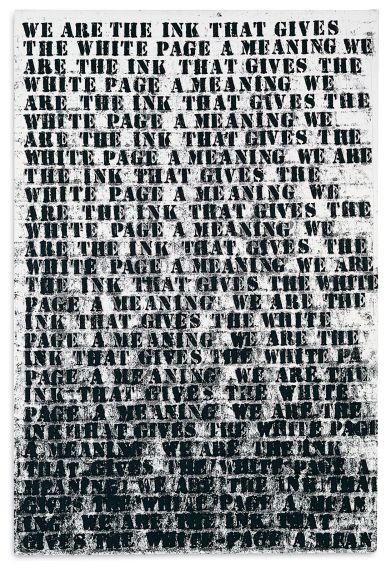

Glenn Ligon,

“Untitled (Study #1 for Prisoner of Love),” 1992.

Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Sandra P. and Jack Guthman, 2000.11

© Glenn Ligon 1992 / Regen Projects, Los Angeles

Photo © MCA Chicago

Exploration of the space and interchanges that occur between the copious number of art pieces will have viewers vacillating between formal and conceptual elements. A palpable occurrence of this is found in a pairing of Imi Knoebel and Glenn Ligon paintings. Carefully considering the identically sized canvases reveals some curatorial motive. Both paintings are highly textural in nature with different sheens of finish on either one. Ligon’s “White #11” (1994), is matte black with some almost illegible over-painted appropriated text concerning the representation of whiteness in film. A few feet east hangs Knoebel’s shiny black and deeply scarred oil on Masonite piece “Untitled (Black Painting)” (1990). Gestural calligraphic lines are gouged angrily into the hard surface hairy-scary, lending an air of exasperation to the greasy ebony surface. The painting is at once minimalistic and expressionistic and practically exudes the frustrations felt in the repetitive prose on Ligon’s “White #11.” Aptly titled for the exhibit, the pair works harmoniously, explaining what “Color Bind” achieves throughout.

Certain objects in “Color Bind” were chosen specifically as demonstrations of what a monochrome work of art can be — or do. Félix González-Torres’s “Untitled (The End),” (1990), is an audience consumable work in which each viewer activates the art by removing — or collecting — one of the 22 x 28” prints. Appearing initially as a minimalist sculptural cube with a white top boasting a one-inch black border, the piece undermines the steadfast relationship between the artwork and audience. “Untitled (The End)” also functions as a metaphor for the body because, as the stack becomes exhausted, it gets replenished. The cycle continues until the stack has disappeared completely and the work has realized its prophetic title. Each print exists as blank canvas for each collector to project any imagined visual onto. Beckwith creates a double entendre for Gonzalez-Torres’s work to function within “Color Bind”— helping the audience indulge their own imagination, within their in-progress discourse, while it develops inside the exhibition space.

No doubt, there’s much more than meets the eye going on in “Color Bind.” The above-mentioned examples hardly scratch the surface. Several artists — including Kerry James Marshall, Kara Walker, Adrian Piper and Valerie Belin — broach topics about racial relations through distinctive expressions. There are literally small surprises from Joel Shapiro. A huge-scale Rudolph Stingel photo-realistic painting provides some commentary on depression and mood. Overall, “Color Bind” is an impressive assemblage from the MCA’s permanent collection and an ambitious experiment that’s fruitful on several levels. Many topics are covered from gender politics and racial tensions to art for art’s sake and diminished mental capacities. While you’ll encounter these societal issues, you won’t go away feeling you’ve been lectured at. Rather, one is left astonished that monochromatic objects could convey such dissimilar yet interconnected ideas.