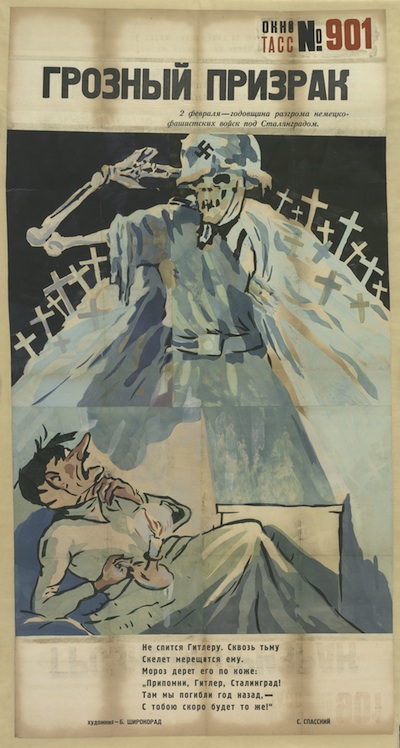

B. Shirokrad. Russian, 20th century. A Menacing Ghost, February 4, 1944. Multicolor brush stencil on newsprint (pieced), laid down on tan Korean lining paper. 1670 x 869 mm. The Art Institute of Chicago. Gift of the USSR Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries. RX21447/0419.

Brandishing pen, pencil, typewriter and newspaper, four grouchy old men charge against the Nazi forces in a dilapidated tank. “I want the pen to be on a par with the bayonet,” declared poet Vladimir Mayakovski, and with him, the slew of artists and writers at Moscow’s Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) who created 1,250 political posters over the course of World War II. Generated to encourage Soviet national pride and fervor in support of the war, the window posters were displayed across the Soviet Union (USSR) and abroad.

In the 1941 poster “Man-Eater,” Boris Efimov portrayed Hitler’s incessant hunger for domination. Hunched over, surrounded by the skulls of France, Greece, Romania, Yugoslavia, Poland and Belgium, he gnaws at a new bone that we can only guess must be the Soviet Union. Unable to defeat the British at sea and move the Western Front forward, Germany turned to the East in a massive invasion of the USSR in the summer of 1941.

That year marked the beginning of TASS’s massive production of propaganda at home and abroad. The posters became a way to rally an American and British audience against German atrocities and cultivate international Soviet allies. Presented as gifts to cultural and diplomatic institutions, art became an ambassador to spread news of the war and to gain support for the Soviet cause. In 1942, the Art Institute of Chicago received 157 TASS posters, which colorfully illustrate the bravery of Bolshevik soldiers, the bestiality of the Nazis and the ultimate villainy of Hitler. Forgotten for half a century, the parcels of folded newsprint sheets were rediscovered in a storage closet by the staff of the Art Institute’s Prints and Drawings Department and are on display for the first time in the exhibition “Windows on the War: Soviet TASS Posters at Home and Abroad, 1941–1945.”

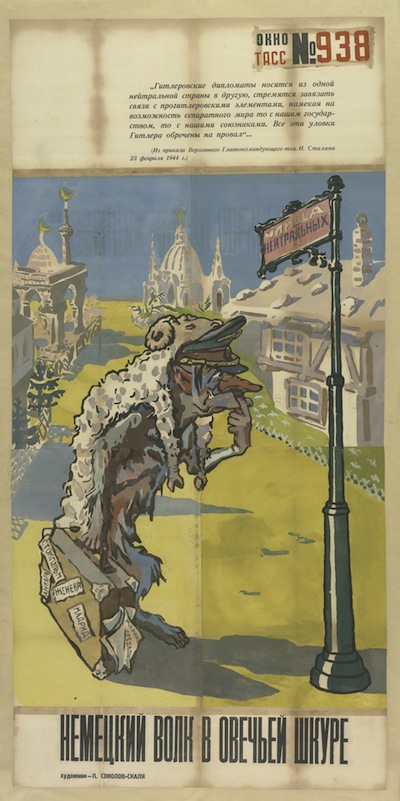

Pavel Petrovich Sokolov-Skalya, Russian, 1899–1961. German Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing, March 22, 1944. Multicolor brush stencil on newsprint (pieced), laid down on tan Korean lining paper. 1872 x 845 mm. The Art Institute of Chicago. Gift of the USSR Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries. RX21447/0431.

With a poster design for nearly every day of the war, TASS created a detailed, chronological portrayal of World War II. Each poster was created from an overlay of 12 to 65 hand-cut stencils, which allowed for mass production. The widespread proliferation and appeal of the bright, saturated, comical posters was fostered by the larger trend of national Bolshevism. Art and ideology infiltrated daily life through posters in storefront windows, schools, theaters and factories. Readily accessible to a largely illiterate population, the TASS posters became a popular forum to spread Russo-centric propaganda about the “Great Patriotic War.”

Praising the TASS posters, the British Minister of Supply, Lord Beaverbrook, remarked that “rarely has the architectural fraudulence of [Hitler’s] ‘New Order,’ the brutality of its racial discrimination and the blindness of its Neanderthal mentality been more strikingly revealed than in these cartoons.” Though the TASS artists succeed in painting a devilishly black portrait of the Nazis, they fail to hold up a mirror and to examine their own nation’s sins. Unlike self-reflexive, political artists such as Francisco Goya or Pablo Picasso, who examine the complex nature of war and destruction, the TASS designers directly project news produced by the communist party along with its version of the war. They do their job and do it well but fail to rise to the level of criticism, especially self-criticism, which is why the Art Institute’s current exhibition of TASS posters will remain an interesting window on World War II, but not a collection of art.

Dear Annete,

These artists were not able to hold a mirror and these posters are not intended to be self-reflexive. If they would have held a self-critical mirror, they might as well have seen a dead face there. Your analysis and comparisons lack some basic information.

Thank you,

Inga Bergman