“You don’t need his tricks, you don’t need his trinkets.” — Roberta Flack in Go Up Moses

Capitalist culture is nothing new to the museum. The museum itself is a repository for valued commercial goods, the arbiter of taste and the guardian of ever-increasing object value. The exhibition space carries rows of goods neatly displayed, named, and signed. The objects on display carry the agenda of consumption, whether conspicuous or ostentatious. With unabashed abandon, the museum mirrors the aesthetic of a department store. It is no wonder then that the museum store is now the key to understanding the museum. What kind of visitor would you be if you hadn’t visited the store? Who would you be to the museum if you had not claimed your own proof-of-purchase by way of the refined bric-a-brac, otherwise known as junk, that the museum store offers for sale? Would you be considered a true visitor without the exhibition catalogue, the postcards, the lithographs, the t-shirts, the tote, the umbrella, the salt and peppershakers, and the coasters? Quite frankly, if you hadn’t, than you’re a virtual nobody in the capitalist museum.

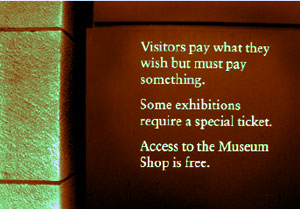

The average net sales per visitor in art museums is $3.42, according to a 2002 Museum Retail Industry Report conducted by a third-party company for the Museum Store Association (MSA), the trade organization of museum retailers. The report also states that the net sales from members within MSA were from $5,000 to more than $17 million, with the median of net sales averaging $137,457 and the mean net sales $415, 074. With the museum store being one of the key sources of income in the privatized world of art funding, it has a major role in identifying the way art is consumed and thereby understood. In fact, it is so important to the institution that it even doubles as a miniature retail reproduction of the actual museum itself. Ironically, you don’t really have to enter the galleries of the museum to see its collection, you can just go to the museum store. The whole collection, and then some, is displayed in pristine and plastificate perfection. The reproductions are prettier, glossier, and closer than the originals, and you can even pick them up. And, what is more, you can own them, they are yours, they become part of your own personal collection. As an added bonus, admission to museum stores are free of charge to the public.

But

how does the museum store infringe on the educational mission

of the museum? The title to a recently published article in

Museum News, a magazine by the American Association of Museums,

highlights the capitalistic direction that the museum is going

towards, “Extending Exhibits, Integrating the Museum

Store.” The museum store is much more than a place to

purchase, it is part of the whole exhibition agenda. Victor

Nemard the store manager for the Corning Museum of Glass (CMOG),

who was a former retailer at Barney’s, underscores the

tension between the educational goals of a museum and the

stores relation to it. As is the case in most museums, the

line between an actual object of art and a purchasable object

are blurred. Exact replicas of pieces housed in the galleries

can be found in the museum store itself. Nemard states that

curators working at CMOG are concerned about intellectually

devaluing the pieces in the collection but maintains that

for visitors the store is still “exciting.”

But

how does the museum store infringe on the educational mission

of the museum? The title to a recently published article in

Museum News, a magazine by the American Association of Museums,

highlights the capitalistic direction that the museum is going

towards, “Extending Exhibits, Integrating the Museum

Store.” The museum store is much more than a place to

purchase, it is part of the whole exhibition agenda. Victor

Nemard the store manager for the Corning Museum of Glass (CMOG),

who was a former retailer at Barney’s, underscores the

tension between the educational goals of a museum and the

stores relation to it. As is the case in most museums, the

line between an actual object of art and a purchasable object

are blurred. Exact replicas of pieces housed in the galleries

can be found in the museum store itself. Nemard states that

curators working at CMOG are concerned about intellectually

devaluing the pieces in the collection but maintains that

for visitors the store is still “exciting.”

The meaning or connection to an art object is hardly deprived to the viewer/visitor/customer of the museum store. The bond of “closeness” to art is initiated by the word “museum” within the phrase “museum store.” Likewise, this closeness can be inferred in Walter Benjamin’s assessment of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. Art is no longer dependent on its “aura,” because “for the first time in world history, mechanical reproduction emancipates the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual.” To consume and accumulate the already consumed collection of museum consumption makes you want to know more about the “rituals” of the artifacts in question. It also makes you defer to the museum as the origin of artistic knowledge. The museum store is more than a retail annex, it is also the cultural embassy of knowledge. It is the concierge and gatekeeper of scholarly goods. It is were you not only go to buy, but also to conspicuously learn.

So is the museum a place of learning or is it a covert retail franchise? For the minority who still try to consider the museum as an institute of education, it’s hard to give in to the reel that is retail in the museum. But the museum as an institution must by force involve itself in the market. The museum, hoever, also acts as the Headmistress of Art to the local population. Like the verse in Roberta Flack’s “Go Up Moses,” some of us want to be rid of those tricks and trinkets. But if Moses is going to rise, inevitably the pharaoh is going to have to go. Unfortunately, the museum also happens to need a Daddy Warbucks, and if all we have to do to let him go is to let him go, where is the money going to come from? The golden calf that is the museum store? Or the non-existent Pharaoh that is art funding?

The pickle is far from kosher when we realize that the Museum Store is a vital source of income to the museum. Perhaps reexamining the Museum Store as the portal of capitalist evil in the art world is going to the extreme, but, then again, when was the last time your stomach convulsed after seeing Da Vinci’s Last Supper plastered from Timbuktu all the way to Yonkers? Does reproducing and then selling art add to its appreciation or to its subsequent downfall? Does the museum store aid and abet to this degradation? Or is the museum store an impetus for inspiration? Furthermore, does the museum store perpetuate the divide between art as consumption and art as social function?

That the consumer is the model art scholar is nothing new. Collectors that started major museums were consumers themselves. That art is a commodity should by no means be a shock. Maybe what is evil isn’t the store so much as a the museum’s administration making the store its priority. If the museum invested the money poured into postcards and various other accoutrements, and instead channeled money to community outreach and education; the collection of art for the consumer wouldn’t necessarily have to be objects, it could be knowledge.