The Other Other

Japanese Artists Nara and Takano Have a Twisted Simplicty

that Has Been Overlooked.

By Erik Wenzel

These days the Other is in. The last Western art fad - the Young British Artists - have one foot in last century and the other in the "has-bin." Globalist art, as the critics and curators are calling it, is the new thing. Basically globalist art calls for artists to no longer be just one nationality. You either have to be from some exotic place and study in the West, or be from the West and study in a non-Western country and become an expatriate.

Westerners are becoming bored with the West and are now looking outside of the U.S. and Europe to what has been going on in other regions since ... well, forever. Landmark shows like The Short Century and the William Kentridge retrospective examine art from Africa. Yes, yes, I know Kentridge is white, but he is indeed a third generation African and his work deals with South Africa and its relationship to the West. (At least that's what it's being packaged as, even though it seems to be more about using South Africa as a backdrop for personal narration.) So there have been all these articles on globalist art in art magazines and important shows in South America like the upcoming Cuban biennial and, for once, these previously overlooked "others" are getting some attention.

It seems that every jet-setting curator's scramble to find the newest untapped demographic inevitably leaves some group in the dust. Japanese contemporary artists are one such group - specifically the artists in Takashi Murakami's Hiropon circle. If you asked the powers-that-be in the Western art scene about the Japanese art scene, they would probably say in response, "Didn't we do that already?" Clearly post-colonialist issues are much more fun for people today to argue about than whether or not Japanese culture is flat or "superflat." Murakami and his ilk have gotten their fair share of attention, but as Murakami himself gains more notoriety, the artists around him are getting lost.

|

|

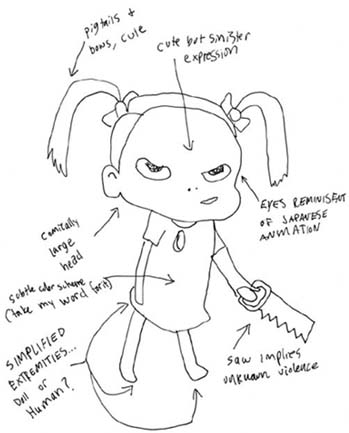

Yoshitama Nara, Handsaw, 1999

Colored pencil, acrylic on paper

18" x 12" Courtesy of Marianne

Boesley Gallery, New York |

Takashi Murakami is a painter-cum-businessman-cum-curator. He runs a factory of artists that makes all sorts of merchandise, from fine art paintings for the discriminating collector to watches for the kid in all of us. The Hiropon factory ("hiropon" is Japanese slang for "heroin") also puts out numerous monographs on artists in the Japanese art scene. Murakami curated a show of such artists, which touched down on American soil last summer, called Superflat, which is also the name of his theory about Japanese culture - that it is not only flat, but superflat. Murakami sees Japanese culture's transition from a traditional background to a current obsession with mass consumerism as a process of flattening. His theory also notes how incredibly flat and two-dimensional Japanese art has been and still is today. The term has kind of become a slogan or brand name in Japan, like Air Jordan in the U.S. But it seems to me that no one really started talking about the work in Superflat until it was over, and today the topic remains filed away in the back of Art Forum's closet.

Murakami's own work is churned out a la Jeff Koons and Andy Warhol. He plays off the stereotypical look of Japanese animation (sci-fi styling, big eyes, highly sexual and violent content) and recontextualizes it in a high art setting, which is a lot more interesting than it might sound. Murakami had a token piece in the super-duper show Beau Monde. "Geesum crickets!" I exclaimed upon seeing that Beau Monde was covered in every single art magazine, but then I realized it was only because everyone's favorite air guitarist, Dave Hickey, curated it.

Murakami himself has managed to remain in the spotlight, but the other talented artists in his circle have fallen to the wayside. Long before I'd heard of Takashi Murakami, one Yoshitomo Nara made a drastic body of work that dealt with all the things Murakami does: contemporary Japan versus traditional Japanese culture, and how it all relates to the West. Nara made the bold move of painting over Japanese woodblock prints with his images of badass, horrific little kids and their dogs. Everyone since Manet brings up Japanese woodblock prints whenever talking about Japanese culture, so what better cultural icon for Nara to appropriate and deface? This work was interesting because it addressed a culture not just in relation to itself, but also in relation to other cultures. It talked about youth versus age, high versus low art, violence, sex, crudity, innocence, art history, and the list goes on.

|

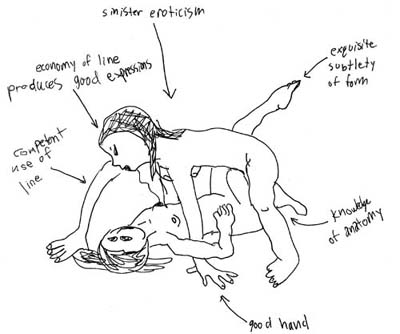

Aya Takano, Perverted, 1997

Watercolor on Paper

181x257mm

Courtesy, Kaikai Kiki. |

It is unfortunate that we in the West have been conditioned to automatically think of Japanese woodblock prints when Japanese art is mentioned. Equally automatic is the thought of Animé/Manga when contemporary Japanese culture is brought up, making Nara's devious children, which look like some scientific endeavor to render Animé cartoon characters human, all the more provocative.

While both Nara and Murakami are very intelligent individuals, Nara's work more readily displays his vast knowledge of contemporary Japanese culture, as well as Western history; it possesses a general, ubiquitous learnedness. Nara incorporates many things into his tiny, obsessive drawings and his grandiose, meticulously structured paintings. Perhaps one of the greatest qualities of Nara's work is its ambiguity. There are many ways to read the narratives and figures in his images. I like that while certain characteristics of his people - the exaggerated size of their eyes and heads, for instance - are firmly rooted in the aesthetics of Japanese comics and animation, other things - such as his color palette and application of paint - can be linked to traditions in Western art. (Talking about Nara's colors and application, as well as his ambiguity, makes me think of the Belgian enigma painter Luc Tuymans. Nara's work is perhaps what Tuymans would make if he didn't take himself so seriously.)

One of the main things that draws me to Nara is his dark sense of humor. He takes things seriously, but not too seriously. He is never afraid to give us a good-hearted laugh with, say, a little girl who has cut down a flower wearing a fiendish grin and a "Fuck You" t-shirt. That is one of the greatest differences between a lot of contemporary Japanese art and its Western counterpart.

Another artist who is very much in the "superflat" shadow is Aya Takano. She works in much the same vein as Nara, creating ultra-precious drawings and paintings of various small sizes - some so incredibly miniscule that they are measured in millimeters. You could say her figures, which wrestle, play, kiss and hang out, look more "human" than the typical style popular in Japanese art. Nara's wonky children look like nature's cruelest mistake from the Aphex Twin video "Come to Daddy" by Chris Cunningham. Although they are extremely distorted and stylized, Nara's characters are rendered in a way that gives the illusion of three-dimensional form. Takano's figures, while more anatomically correct, remain thoroughly two dimensional.

Aya Takano's two-dimensionality has more in common with the graphic work of early Modernism in Europe than it does with current Japanese aesthetics. Her handling and application of materials achieves a distinctly non-flat, aggressive feel. In harsh contrast to the super-controlled lines of Animé, her lines dance, play and wrestle throughout. Her work has a striking resemblance - not only in aesthetics but in subject matter - to that of Egon Schiele (I am forced to bring it up). It is interesting to compare the work of a man living in Vienna during World War I, which depicts girls in sexually charged situations, to work of the same ilk by a young woman in modern Japan.

What I find most interesting is work that not only brings up new ideas, but also leads us to look back at familiar things in new ways. If art ever is going to mean anything, it will be achieved by those who can get us to look at art as something naughty, dirty and funny, and at the same time beautiful, serious and profound.

|