In an extended investigation that partially culminated in her MFA Show installation in April this year, Efrat Hakimi (MFA 2019) used her time at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) to investigate the controversial origins of the field of gynecology in the United States of America.

For Hakimi’s MFA Show video installation, “In Situ,” she presented two to-scale paper barricades that stood guard in front of the two paper embossings and a two-channel video installed on the wall. The process of bringing together the installation began with the footage of an art historian defending the monument at a public meeting (part of the two-channel loop). In defense of the monument, the art historian tells us: “History matters. Don’t run from it.”

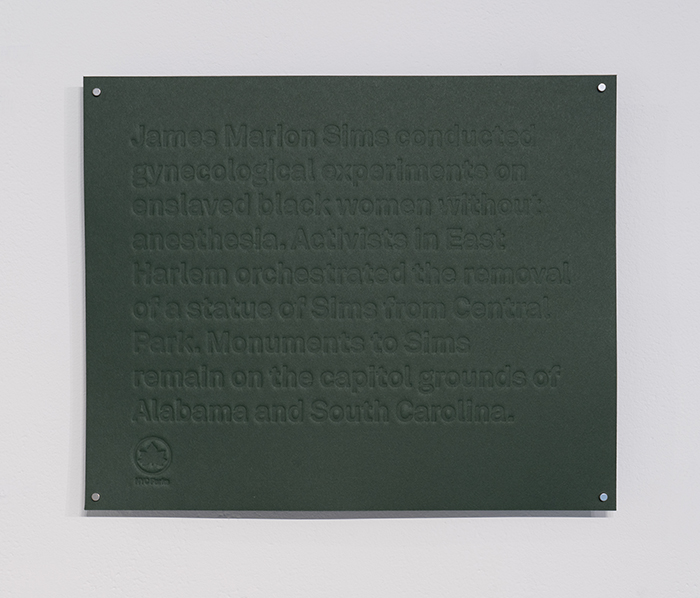

Hakimi’s work began with her intrigue around the speculum, a medical tool used in gynecological exams. The first part of her research looked at the tool itself, but took a turn when she began to discover its history. She found out that the speculum as we know it today was prototyped in Alabama in the mid-19th century by James Marion Sims, who between 1845 and 1849 experimented on enslaved black women that were brought to him because they suffered from vesicovaginal fistulas — a painful condition that occurs after prolonged labor.

Sims experimented extensively on a number of women, only three of whom are named in his records: Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsy. Though he claimed he obtained consent from these women, some of whom he operated on without anesthesia as many as 30 times, no other record of their consent exists (and as slaves in any case, the possibility for true consent is questionable). During a very successful career, Sims also performed at least one clitoridectomy and a number of “normal ovariotomies” — a practice in which to cure dysmenorrhea, diarrhea, or epilepsy, one or both healthy ovaries are removed — that mutilated some women and killed others.

“At first I considered this research from my own feminist point of view, but then I realized it gives a vantage point on these really painful, still bleeding areas of American history,” Hakimi said.

“It’s such an important piece of living history and I was fascinated by that, and also by the fact that the history so physically ties back to our bodies… we are somehow connected to this story through our own reproductive health.”

Sims eventually discovered cures for many ailments, but even some of his colleagues thought many of his procedures resulted in needless harm to the patient. British and French doctors also agreed that his treatment for vaginismus was unnecessarily dangerous and invasive, and the New York Academy of Medicine put him on trial in 1870 for violating patient confidentiality by writing publicly about the condition of a celebrity he had seen in private practice.

For his experiments, Sims chose lower-class or enslaved women over upper-class white women, who would have had more opportunity to advocate for themselves and have others advocate on their behalf. His acts do not stand alone in the history of this country: Between 1932 and 1972 in the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiments, known treatments for syphilis were withheld exclusively from black patients; while in 1951 the cells of African American farmer Henrietta Lacks were taken without her consent and have since been used in the development of various scientific break-throughs, raking in high profits without any compensation to Lacks or her family, who only accidentally learned her cells had been turned into research material.

Sims died in New York in 1883. A group of his followers commissioned a monument to his memory, which was subsequently donated to the city and placed in Bryant Park. Thirty years later, the location was being renovated; the sculpture was removed and placed in storage under the Williamsburg Bridge. The City Commissioner of New York later happened across it and decided to re-erect it outside Central Park, at 5th Avenue and 103rd Street, in front of the Academy of Medicine and near Girls’ Gate.

At the end of Hakimi’s first semester at SAIC, an article was published in Harper’s on the monument and its calls for removal. Shortly after, a Mayoral Advisory Commission released a report recommending to relocate it, which the mayor subsequently acted on.

“For me it’s really fascinating the way this monument came into the city,” Hakimi said. “It’s not that the city held a forum to decide who to commemorate. Rather, the moneyed friends of a powerful person bought the honor in his name. But 100 years later, people are saying, hold on, there’s a controversial history here, he’s not our hero, we don’t want this in our neighborhood. It takes almost a decade of effort, and then it takes Charlottesville for Bill De Blasio to put together a commission of outside experts to look at all the contested monuments and see if we need to remove any of them.”

The report mentioned three other controversial statues: Christopher Columbus, Henri-Philippe Pétain, and Theodore Roosevelt. Of the four, Mayor De Blasio only ordered the relocation of Sims’, to Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, where he is buried. With a couple of small exceptions, no statue has ever been permanently removed from the city.

“There’s this climate right now of people saying that history and ideology are intertwined and we can open a conversation about what should be in public space, but then they don’t go all the way to remove this person who had committed moral crimes. It’s a perpetuation of the same behavior, where it’s more about things being out of sight than paying the price or actually letting justice take place.”

Hakimi hoped to work with the City of New York to escort and film the process of the monument’s de- and re-installation, but despite her best efforts she couldn’t get the City to respond. Rather, only two days in advance she found out from East Harlem Preservation, Inc. — the group that has called for its removal for nearly a decade — that it was going to be relocated.

Hakimi rushed over to record the process, but the relocation did not take place; instead, the monument was taken down and put in storage once more. On the still-standing monument platform, the city installed a placard that explains that the monument was removed by order of the mayor and that a new monument will be erected in its place.

“Empathy was never part of a lot of it: it wasn’t part of Sims’ experiments, and in a way it wasn’t part of the city’s decision to remove the monument,” Hakimi said.

Hakimi later added footage of a news reporter speaking in front of Sims’ empty platform to play alongside to the art historian’s speech. Each woman (the historian and the reporter) offers a different framework for the story. One of Hakimi’s embossings offers the artist’s own version of the narrative, in the form of an alternatively worded placard that focuses on the history of the monument and its calls for removal.

Hakimi made the paper barricades that stand in front of the video screens in consideration of the barricades that have surrounded the monument since protests at the site began in 2017.

“It’s this symbolic barrier being used to protect what belongs to the authorities or what should be protected by the state or the city,” Hakimi said.

When asked why she chose to work in paper, Hakimi said it was a long-term medium of her practice but also reflective of the research, bureaucracy, and materiality that surrounded the monument’s history.

“When we go to the gynecologist and we lay on the table, we’re in this very vulnerable position for our body to meet an intrusive foreign object. I see this monument as this very intrusive, hard material also, so I thought, how can I fragment or interrupt that? How do we rebuild things using the right materials? Using a softer approach, a translucent approach?”

The City of New York has created an open call for proposals for a work to take the place the monument. In her proposal, Hakimi offers to do away with the idea of a static monolith, turning the platform into a stage that can host the work of various artists over time.

Two other monuments to Sims remain standing — one in his home state of South Carolina and the other in Alabama, where his initial experiments took place.