What changed this summer, and why you should care

By Nick Briz

These days, when it comes to legislation on the wild web, it’s nothing but bad news for Internet users all over the world. Tighter locks like Canada’s newly passed copyright reform bill, Bill C-32, and the U.K’s Digital Economy Act, which controversially regulates digital media, represent extremist legislation meant to enforce tighter boundaries for what gets produced, and reproduced, on the web.

But on July 27, thanks largely to public interest groups such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), the Library of Congress passed a handful of exemptions to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), a law that prevents consumers/users from breaking digital locks on their products/devices and criminalizes the circumvention of the locks put in place even when there is no violation of copyright.

These exemptions are a progressive step forward in the mess that is digital law today — but before we pop open the champagne, it’s important to understand the role of “digital locks” and their place within the world of Digital Rights Management (DRM). While such terms might sound like the preoccupations of tech nerds, they have an effect on everyone who reads, listens to, and watches content on the web, and an even greater effect on artists and their ability to create and produce in our increasingly powerful digital landscape.

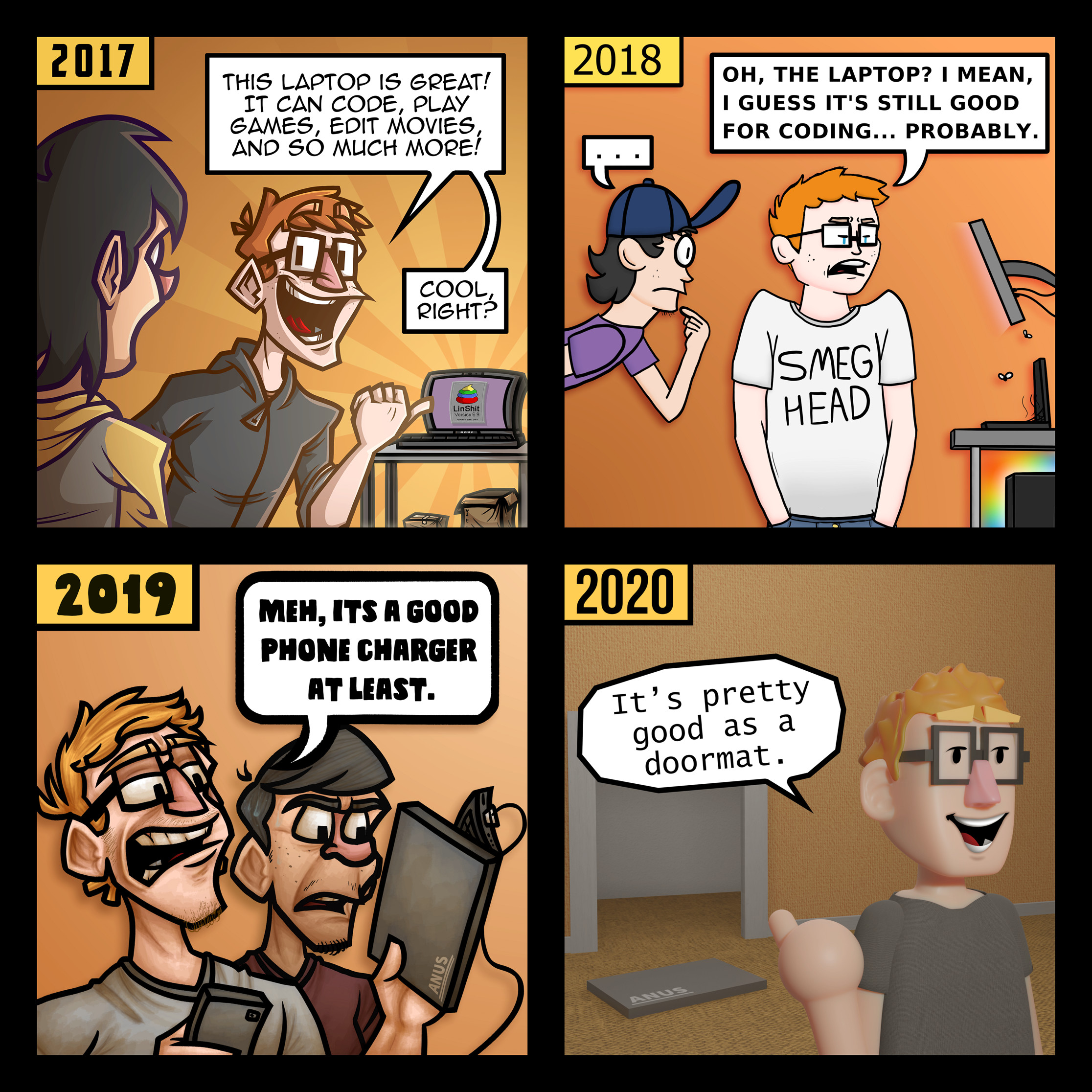

DRM is what happens when innovative technology companies (like Apple — a company once dedicated to the idea of open modifiable hardware/software) get into bed with the entertainment industry and the telecoms (wireless/phone companies).

Imagine for a moment that you’ve purchased a bookshelf from Target and the only books you’re allowed to put on that bookshelf are books you purchase from Target’s abysmal book selection. Now that you’ve filled that shelf with hundreds of dollars worth of sub-par Target books, you want to buy a newer, trendier bookshelf from Ikea, but you can’t legally (and without great difficulty) move your books from your Target shelf to your Ikea shelf.

Furthermore, imagine that every time you try to photocopy a page from your books for your class project, the copy-machine spits out a paper which reads “You do not have permission to copy the contents on this page.” You can’t even lend any of your books to a friend. What’s worse, at the end of the day you’re not even allowed to trade or sell these worthless books at your local used bookstore.

Thanks to DRM, this is exactly how devices like the iPad work. It’s sad to think that a company that once packaged their computers with schematics encouraging users to edit/modify/hack their products now requires you to have the batteries changed by professionals (as is the case with the iPad). There are no screws on this bookshelf; only super glue.

Cory Doctorow, digital rights activist and children’s novelist, writes on his blog, craphound.com: “As a copyright holder and creator, I don’t want a single, Wal-Mart-like channel that controls access to my audience and dictates what is and is not acceptable material for me to create.” These “single, Wal-Mart-like channels” exercise their power via the DRM they implant into the digital content which passes through their stores. As makers, the inability to modify our tools isn’t the only setback.

I can’t imagine a world where Barnes and Noble would dare tell Anne Rice to change the ending of her book before they put it on the shelves — but that’s exactly how it works with iPhone/iPad apps which can only be legally purchased on the “single” Apple-controlled store. With the digitization of media comes a dependence on digital technologies for distribution, and while this technology creates amazing possibilities, the industry, more comfortable with their old models, finds ways to force limitations on them.

This bureaucracy reached SAIC this summer when Shawn Decker’s class for creating applications for mobile devices like the iPhone got cancelled, and it wasn’t due to low enrollment.

Decker might have better luck next summer as the market for apps opens up, thanks to these new exemptions to the DMCA. It’s now legal to “jailbreak” your iPhone, which means with a simple click of a link you can open your iPhone up to a whole world of apps that for various reasons have been “disapproved” by Apple.

The exemptions go beyond jailbreaking iPhones. Say you want to “screen cap” an image from a movie for your class presentation, or rip content off a DVD and satirically remix it. Or say you’re blind and want to take a digital book you’ve purchased and open it with your read-aloud software.

Previously, these things were impossible to accomplish without illegally breaking digital locks with illegal software. Now, thanks to EFF, these formerly illegal actions will be within the full rights of all media users.

Jennifer Stisa Granick, EFF’s civil liberties director, says on the group’s blog that the rules are based on a very simple idea: “If you bought it, you own it.” Common sense, maybe, but not common practice.

So, although the champagne’s been popped, it’s important to note that these exemptions leave many questions unanswered. If you break codes on your iPhone, will it still void your warranty? Does this mean it’s legal to sell software that breaks digital locks (DRM-ripping, iPhone jail breaking, etc.)? Breaking the lock on a DVD to remix the content is no longer illegal, but, how far does “fair use” go?

Only time will tell. All in all, it’s a happy moment for digital rights.