Jeremy Deller at the MCA

by Beth Capper

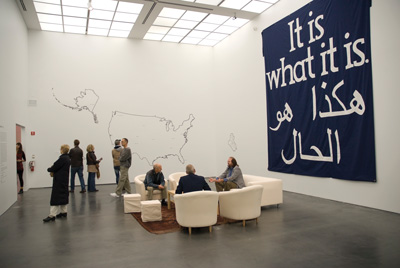

This is the scene: A coffee table is laden with “Middle Eastern” cookies and an ornate silver teapot. Paper plates and polystyrene cups are provided. Flanking the table on all sides are armchairs and sofas to sit upon. The setting is supposed to be as casual as a friend’s living room; the only minor difference being that we’re in the Museum of Contemporary Art.

This is the scene: A coffee table is laden with “Middle Eastern” cookies and an ornate silver teapot. Paper plates and polystyrene cups are provided. Flanking the table on all sides are armchairs and sofas to sit upon. The setting is supposed to be as casual as a friend’s living room; the only minor difference being that we’re in the Museum of Contemporary Art.

A small crowd gathers; some sit down, others stand. All eyes are fixed upon an Iraqi man with a name tag and a long ponytail. Some onlookers ask questions, but most don’t. One woman dominates the conversation for a time with questions about the Iran-Iraq War. The man calmly and earnestly answers her questions, going to great lengths to disclose as much as possible.

Just as the seated audience awkwardly pour themselves lukewarm tea and nibble on the snacks provided, the Iraqi man sinks his teeth into a large chocolate chip Brownie from the MCA’s Pucks cafeteria. The cultural commentary inscribed in this particular moment is priceless.

The man’s name is Esam Pasha, and he is part of “It Is What It Is: Conversations About Iraq”; the new blockbuster Jeremy Deller exhibition at the MCA through November 15. Pasha is one of a rotating cast of scholars, activists, journalists and Iraqi nationals Deller has enlisted to act as “experts” about the war for the sake of the exhibition. To call Deller the artist of the work is a stretch. He’s more of a community organizer, or perhaps a facilitator of engagement.

These experts sit in the gallery, in three hour-long shifts, ready and willing to have unscripted conversations with members of the American public about their experiences of the war. Objects and didactic materials meant to spark discussion are located around the gallery, including the remnants of a car destroyed in an explosion in Bagdad that killed thirty eight people in 2007.

There is something troubling about the way in which this engagement is set up. From the positioning of his participants as experts right down to the snacks on the table—a gesture that, while ostensibly naïve, can also be read as a troubling emblem of the West’s commodification of “other” cultures.

As far as experts go, Pasha has the right credentials. He worked as a translator for the armed forces and press in Iraq, and he also painted over the first and largest mural portrait of Saddam Hussein when the leader was deposed in 2003, covering it with his own interpretation of the country’s history. But when I ask him during the exhibition how he feels about being deemed an expert, he appears a little uncomfortable with it.

The exhibition raises the question as to who is at risk in the engagement Deller initiates. There are participatory art projects that place the artist in the precarious position; for example, Joseph Beuys arguing about direct democracy with crowds at Documenta 5, Yoko Ono asking audience members to decide whether or not to remove small squares of material from her body in “Cut Piece,” or even Rirkrit Tiravanija cooking Thai food for hungry New Yorkers out for a free lunch. However, in Deller’s work it is often his participants who undertake the risk, demonstrated poignantly in his most famous work, “The Battle of Orgreave,” where miners and police involved in a violent clash during the 1984 Miners Strike in England were asked to reenact their experiences.

Deller, Pasha and Iraq War veteran Jonathan Harvey undertook a three-week road trip with the remnants of the car in tow, stopping at cultural institutions and community centers in an attempt to incite dialogue about the war. “It Is What It Is” is a continuation of conversations from this tour, but instead of going to the public, Deller is asking the public to come to them.

His decision to situate this conversation in the white cube opens him up to criticism from the outset. Many artists working in similar ways have forgone this context because it produces a kind of forced or false engagement. The hope is that by placing it in this context, the conversation will provoke greater reflection from those involved. Deller not only humanizes the situation in Iraq for Americans who are assumed to have only a tangential and mediated connection to a war waged on their behalf, but he does so in the context of the transcendent art experience. However, does this strategy naïvely put faith in the effectiveness of mere exposure? As theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick wrote in her essay, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading,” “trust in exposure seemingly depends … on an infinite reservoir of naïveté in those who make up the audience for these unveilings. …What is the basis for assuming that it will surprise or disturb, never mind motivate, anyone to learn that a given social manifestation is artificial, self-contradictory, imitative, phantasmatic, or even violent?” Maybe, though, “It Is What It Is” doesn’t have such lofty goals, and instead is simply about saying, as the title goes, that the situation in Iraq is what it is, and what it is has to be dealt with.

The exhibition creates a situation that individuals can orchestrate to their advantage. The MCA advertises which participants speak each day, and the responsible citizen is thus able to do research in preparation. The engagement lags if you ponder not the conversation you are there to have, but whether this conversation can be considered good art, or even art at all. In the end, perhaps Deller is telling us that when it comes to having a meaningful conversation about the war in Iraq, what It Is is ultimately up to us.