By Brandon Kosters

Drawing inspiration from Euclid’s writings about optics, electronic music, and abstract animation from the United States from the 1950s, the work of Dutch multimedia artist Joost Rekveld is hard to describe. Rekveld’s rigorous academic research and preliminary structures result in an ambient visual music, integrating kinetic sculpture, soundscapes, and abstract film. They can be appreciated even if the pieces themselves show little evidence of what informed their creation.

Drawing inspiration from Euclid’s writings about optics, electronic music, and abstract animation from the United States from the 1950s, the work of Dutch multimedia artist Joost Rekveld is hard to describe. Rekveld’s rigorous academic research and preliminary structures result in an ambient visual music, integrating kinetic sculpture, soundscapes, and abstract film. They can be appreciated even if the pieces themselves show little evidence of what informed their creation.

On Thursday, October 8, 2009, Conversations at the Edge hosted “Book Of Mirrors: Films by Joost Rekveld” at the Gene Siskel Film Center, with Rekveld appearing in person. The Amsterdam-based artist studied at the Hague, where he currently serves as the head of the Interfaculty ArtSciences department. Among the numerous issues addressed by the work shown at the Gene Siskel are visual representations of sound, historical explorations of perspective, and the role of technology in modern society, particularly in the context of art.

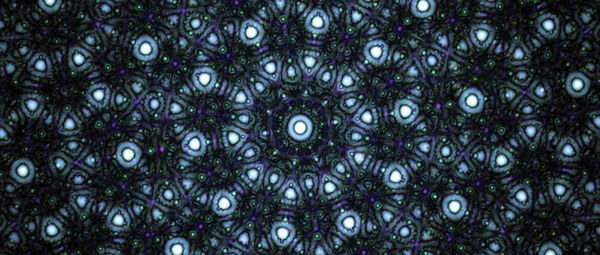

His film “#23.2, Book of Mirrors” was, says Rekveld, “very inspired by the history of optics, perspective, and medieval approaches and explorations. It was determined at the beginning of the 17th Century that if light goes through a very small hole you get interference patterns produced by the light waves.”

To apply this principle to a film, Rekveld constructed a kaleidoscopic box with rails and slits that he could manipulate, with film on one side and a hole for light to enter the box on the other. “This allowed me to work with light oozing through [the box] directly onto the emulsion. I was interested in what kind of images it would produce [and whether or not] you’d get a sense of space that is different to the standard perspective space that is inherent in standard optics.” Faint streaks of light pulsate with accompanying sound that textures the film.

Rekveld builds kinetic sculptures for other works too. Some of these devices have been exhibited as works of art in themselves. For the past six years, he has also been working with computer software to generate imagery. His most recent film “#37” is a computer-driven inquiry into the formation of crystals, made using the computer program Jitter, which Rekveld then transferred to 35mm Cinemascope.

“I was triggered to make abstract films by Oskar Fischinger. Also, post-war American abstract filmmakers like James Whitney, Jordan Belson, and Stan Brahkage. The whole tradition of visual music was very important to me.”

Explaining how he came to visual music, Rekveld says, “My focus was initially very much electronic music. …My dream was to make my own films and my own electronic music. At some point I realized that I like electronic music, but I didn’t necessarily want to make it.”

Rekveld now typically commissions other composers to provide the score for his films. “The composer gets involved at a very late stage … in the sound, they address the same concepts which inform the images.”

Rekveld’s approach to working with composers is based upon “finding a common approach.” Rekveld chooses composers who he can identify with so that he can relinquish control over the sound. Rekveld is resistant to having his work codified by meaning. Indeed, when asked by one audience member at Conversations at the Edge what analogies he is making between music and images, Rekveld dismissed such analogies as “totalitarian.”

His film “#23.2, Book of Mirrors” is the only piece with a “score” in the most traditional sense. It has been played three times with accompaniment from a live ensemble. Rekveld has collaborated in the past with theater and dance companies, producing images in real time using computer software such as Jitter and Max MXP.

“Before, I made mechanical machines to show images. I never really worked to make something sturdy and versatile enough to perform in a live setting.”

While Rekveld’s films are lyrical and captivating by themselves, there is seldom a clear connection to whatever academic research was conducted during the conceptual development of the piece. This is fine with Rekveld.

“It’s very easy to talk about in technical terms, in terms of research and concepts that inform it,” Rekveld says. “In the end [though], what’s most important is the sensual experience.”

As a scholar, and an artist, Rekveld is continually dealing with the correlation between art and science. While he has worked directly with analog equipment and media, he has not shied away from digital formats. “All of these technological or scientific developments … they are … a product of human culture. The first human is a monkey who discovers a tool. Often, technology is seen as this strange alien thing invading our lives, and yet it is also what defines us as human. Part of what I’m trying to do is humanize this thing, make the principles behind some of it accessible to our senses and show its poetic quality.”

Through his work Rekveld boldly challenges the idea that “perception is a passive process. That you can sit still on you armchair and just make sense of the world.” He references René Descartes. “He (Descartes) had this one analogy of a blind person with a walking stick. The world does not just stream in for this person. He is forced to reach into it.”

“This,” asserts Rekveld, “is important when thinking about perception.”

[…] The School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s F Newsmagazine sits down with Joost Rekveld, Dutch filmmaker and current head of the ArtScience Interfaculty in The Hague. Read the full story in the October edition of F News. […]