“Becoming Edvard Munch: Influence, Anxiety and Myth,” currently on display at the Art Institute of Chicago, takes a radical new approach to the retrospective exhibition in its ingenious curation of artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944).

Munch’s The Scream—famously reprinted on coffee mugs, umbrellas and even blow-up dolls and finger puppets—garnered additional attention in 2004 when one of the three versions of this painting was stolen from the Munch Museum in Oslo, Norway. It seems that while Edvard Munch may not be a household name, this painting most certainly is. While there are many reasons for its fame, perhaps this painting is particularly iconic because it seems to reaffirm notions of the creative genius as a tortured soul. Just as Vincent van Gogh is as famous for his insanity as he is for his paintings, so has Munch been slotted as the lone, desperate savant, forced to turn to artistic representation for release in an alienating world. However, with Munch, this may be equally a result of the ploys he used to self-promote, as it is our general fascination with the Bohemian Other.

But do not expect to see this mythical construction of Munch at AIC. As Jay Clarke, Associate Curator of Prints and Drawings and a leading Munch scholar, explained in the exhibition press release: throughout her research in Norway she “kept waiting for the ‘crazy Munch’ to reveal himself… but I never found him. Instead, the letters reveal a man very much in control of his career, even acting as his own dealer and organizing complex exhibitions and negotiations. Indeed, far from an independent, the artist was like a sponge, soaking up painting styles, motifs, and technical tricks from his contemporaries.”

Clarke’s presentation of Munch’s oeuvre is organized around popular themes that occur in his paintings, prints and drawings. Such themes include “Anxiety,” “Death and Dying,” “The Street” and “Bathing.” They serve to evaluate Munch’s work within the context his contemporaries—most notably, Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet, Max Klinger and Vincent van Gogh. This serves to present Munch as a shrewd artist responding to the images and themes of his contemporaries, engaged in the issues of his time.

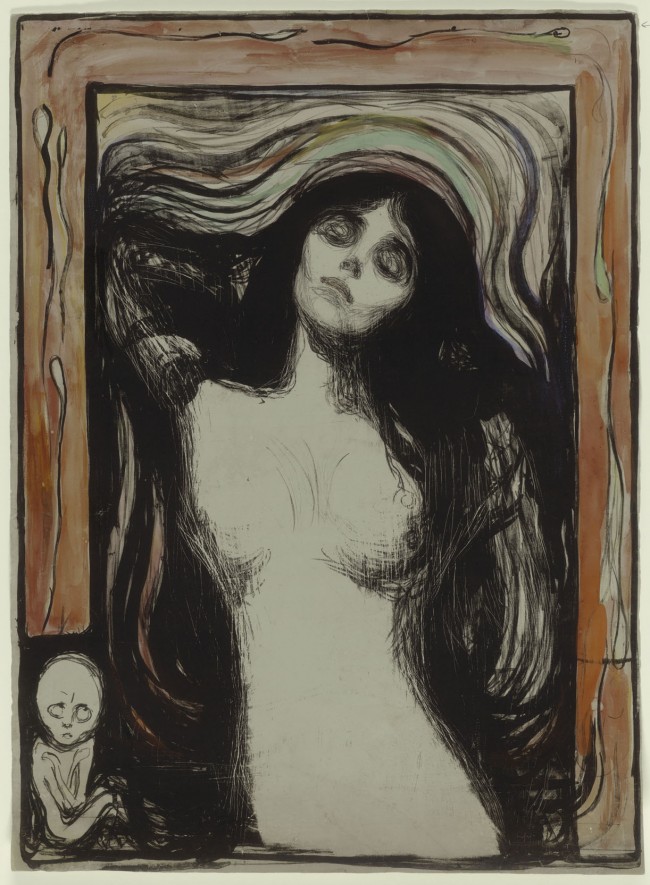

Though you will not be able to see The Scream, paintings such as Kiss By the Window (1892), Anxiety (1894), and Evening on Karl Johan (1892) are some other well-known pieces on display. A small print entitled Flower of Pain (1897) visually represents the persona Munch would create for himself showing the artist’s blood as the source of a blooming lily. A representation that starkly contrasts with the numerous other self-portraits in the exhibition, including the debonair but murky Self-Portrait with a Cigarette (1895), in which the artist stares piercingly out of the canvas amidst a swirl of smoky liquefied paint.

What is most impressive is the number and diversity of images with which he worked, as well as the breadth of the work of others with which he was acquainted. 150 Munch prints and paintings are exhibited alongside 61 works by 43 other artists from whom he drew inspiration. What all of these images and comparisons demonstrate is Munch’s extraordinary ability to represent the intense emotions of men and women, whether in isolation or on a busy street.

Many of the prints exhibited come from the Institute’s own collection displayed in traditional “Munch style” wooden frames. In any given room one may see not only a large oil painting of a striking image, but the same image reproduced with varying colors and techniques in print. Most effective is the display of three prints of The Sick Child (1896) along a single wall. On the opposite wall is hung the larger painting. While these images were responses to the illness and death of his beloved sister Sophie, rather than imply an obsessive reworking of a psychically inescapable image, we see Munch as a keen artist modifying colors and design choices in order to convey a powerful situation. Further, The Sick Child is juxtaposed with fellow Norwegian painter Hans Heyerdahl’s Dying Child (1889), a painting and artist Munch both admired and emulated.

“Becoming Edvard Munch” questions the popular reliance of curatorial practices on the autobiographical and historical presentation of an artist’s persona, and asks what is gained when an artist creates a specific personality, as well as what is lost in our belief in that personality. By placing Munch within the context of his contemporaries, his localities, his conflicting statements and the statements of his peers, a multi-faceted artist reveals himself.

This exhibition should make us all question the singular ways in which we view artists, and recognize that a successful artist must be both creator and businessman, self-promoter and, at times, self-denigrator. Clarke’s refusal to take the Munch scholarship of old and Munch’s words themselves at face value is a bold move that questions established stereotypes and reminds us that identities are both self-asserted and publicly created.

On view through April 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago, 111 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, 60603-6404. Mon.–Wed. 10:30 a.m.–5:00 p.m., Thurs. 10:30 a.m.–8:00 p.m., Fri. 10:30 a.m.–5:00p.m., Sat.–Sun. 10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m.

All images courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.