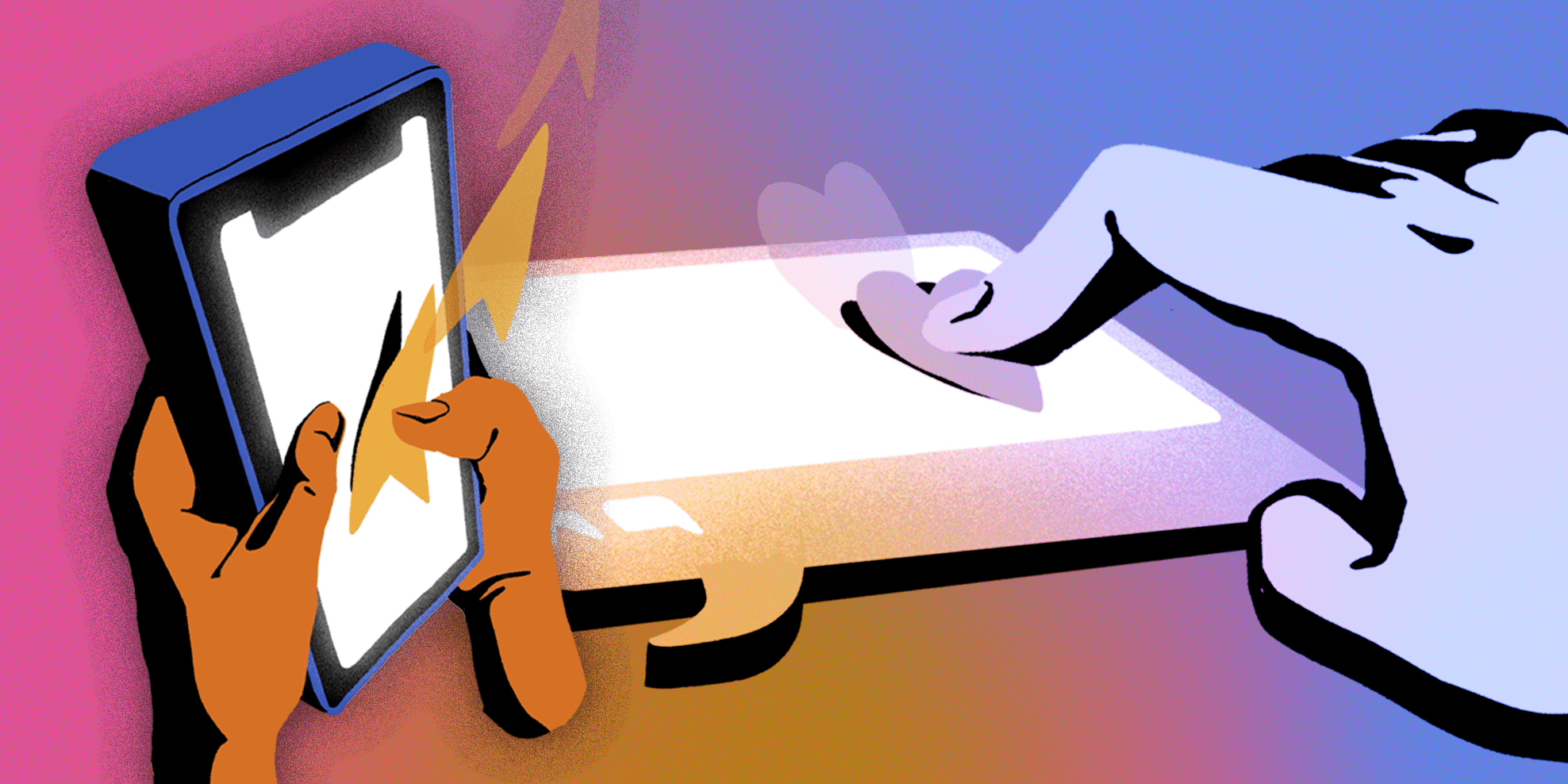

Image from “Night of Bush Capturing: A Virtual Jihadi” by Wafaa Bilal in which Bilal is an avatar who may be sent on a suicide mission by the video-game player.

How popular media misrepresented a controversial artist

Artist and faculty member Wafaa Bilal is no stranger to the national spotlight. But coverage of his recently censored work, Night of Bush Capturing: A Virtual Jihadi, required more nuance and artist perspective than it was typically given in the mainstream media. Here are the details of the Troy, New York controversy you might have missed

Sometimes art that is meant to provoke dialog instigates hateful rounds of misrepresentations and assumptions. No recent story illustrates this more clearly than that of Wafaa Bilal’s. The faculty member of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago was at the center of a media storm in March after Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, shut down an exhibition in which he was showing. What ensued, he said, resembled too well the regime of Saddam Hussein, in which political artwork was censored. It also illustrated a troubling disconnect between an artist and the journalists who relay his work to the public as well as the strengths of “citizen journalism.”

Those in the SAIC community are likely familiar with Bilal’s ordeal. He submitted a proposal to the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute that included his piece, Night of Bush Capturing: A Virtual Jihadi. The work was accepted, but the show was suspended by the administration once the campus College Republicans raised concerns that showing such a work was supporting a “terrorist,” Bilal said. After the show was canceled, the Sanctuary for Independent Media in Troy invited Bilal to exhibit Virtual Jihadi. However, outcry from local politicians resulted in this show closing, as well; the official reason cited for the shutdown at The Sanctuary was that the doors of the facility did not have the correct hardware or measurements.

Since then, major media outlets including the Washington Post and the Chicago Tribune have covered the reactions to this art. Many of the stories in the mainstream media provided little of Bilal’s perspective on the issue. And the Tribune showed its true colors in the wording of a headline that read, “Artist claims ‘censorship.’ ” By using the word “claim” and by using quotes around the word “censorship,” the Tribune plays in too-safe territory and ends up (perhaps unwittingly) appearing to question the validity of what happened to a man whom only months ago they named “Artist of the Year.” It is one of many media phrasings that highlight how artists’ viewpoints are maligned in popular news coverage. Meanwhile, a video interview of Bilal circulated on YouTube and “independent” media web sites, one of the few venues besides the artist’s own web site in which a broader version of his perspective was fleshed out.

Nonetheless, the censorship of Bilal was steeped in issues of nationality and controversy that are irresistible to journalists. Artists are censored in some form or another by organizations across America. So why all the hubbub about Bilal? The answer is obvious. He is an artist of Iraqi descent whose brother was killed by shrapnel of occupying forces. It is both intriguing to hear his perspective and easy for some to mush him in with terrorists simply because of popular and rarely contested notions about people from Iraq. Bilal also has relative fame after national coverage of his 2007 work, Domestic Tension, in which he invited internet users to shoot him with paintballs as he lived for one month at Flatfile Galleries.

The point of that piece was clear and easy for the media to relay: Shoot an Iraqi, if you must. By comparison, the work at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute was not as clear in intent. Or, at least, it takes more nuance and a few more sentences to explain the work. This is where some news outlets tripped up in telling his story.

“It’s a bit different from Domestic Tension because a lot of people agreed on Domestic Tension,” Bilal said. Night of Bush Capturing: A Virtual Jihadi is the third well-known adaptation of a video game called Quest for Saddam. In the original video game, Bilal says, all the Iraqis look the same (like Saddam), and they make stereotypical noises that offended Bilal as an Iraq native. However, a second and relatively widely known version was allegedly made by an al-Qaeda media group in 2005, Bilal said. This version is called, simply, Night of Bush Capturing. In it, appearances and skin colors are reversed, and players are poised to do exactly what the title of the game implies.

However, Bilal said, it appeared there was confusion in some media outlets that might have led people to believe Bilal himself had created the version that the al-Qaeda media group reportedly made.

But in Bilal’s version, A Virtual Jihadi, Bilal is an avatar who can be an expendable Iraqi suicide bomber. He used himself because he is an Iraqi who lost a family member and who is outraged by the continued occupation of Iraq. In his version, players are on a mission where they can encounter President George W. Bush and shoot him (and Bush shoots back). Or a player can plant a suicide bomber next to the U.S. president, and the suicide bomber is positioned as yet another “expendable” Iraqi, according to Bilal. It is also possible to send Wafaa’s avatar on a suicide mission in his version.

The irony is that Bilal was invited to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute to interact with students and bring awareness about Iraqi issues. A Virtual Jihadi was designed, in part, to counter racist and nationalistic attitudes. Bilal had aimed through the work to point to Iraqis’ vulnerabilities after the U.S. invasion in 2003. The game, he said, is designed to show pressures Iraqis face to adopt violence as a means of objection. Bilal said people often try to deny the factors of discrimination, hatred and stereotypes that exist in the war, and this, in part, led him to create A Virtual Jihadi.

“I was amazed by how the simple act of reversing skin color could outrage people,” Bilal said.

In Troy, Bilal observed how sound bites are easily manipulated by those in leadership positions who had never played the game or even seen it. The pressure of this rhetoric appeared to take place of constructive dialog. His story, it appears, also illustrates artists’ roles as proverbial canaries in coal mines.

“Artists are always on the front line of the issue, art is on the front line of the issue. If you silence them, what happens?”